Self-care for the client/patient:

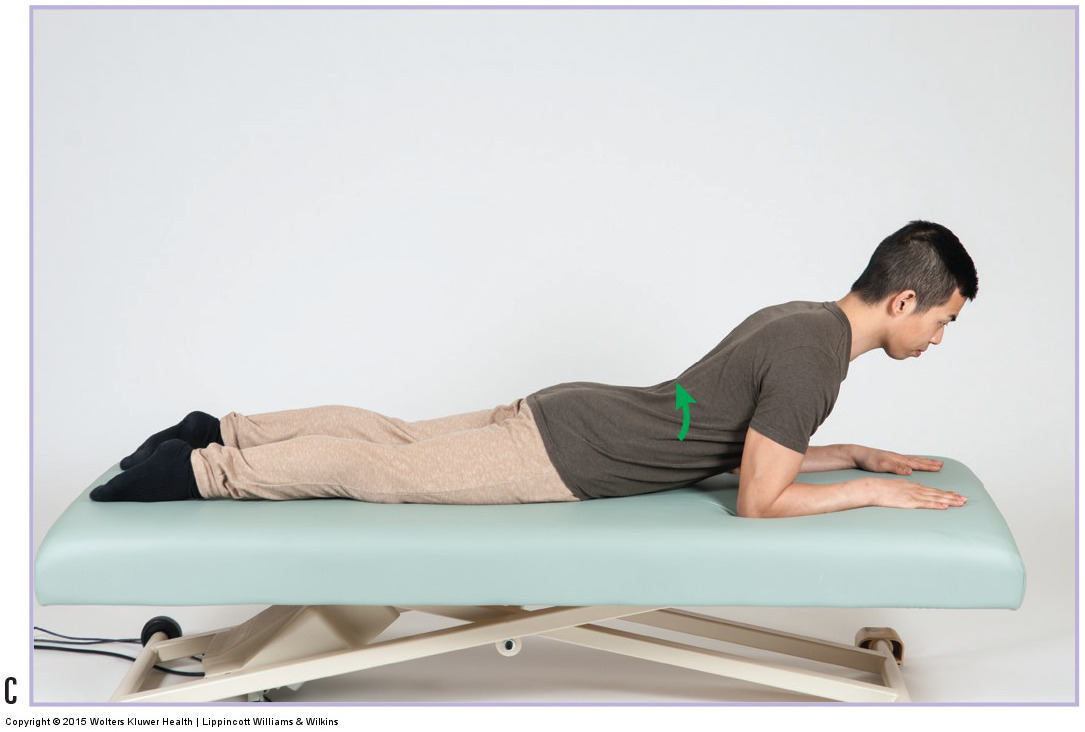

Extension exercise for a pathologic disc. Permission: Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach (2015).

Self care for the client/patient with a pathologic disc (disc bulge, herniated disc) involves avoidance of postures and activities that increase stress upon the disc, and stretching and strengthening the associated musculature. The most egregious postures for lumbar discs are prolonged sitting and standing, bending over (especially stoop bending), lifting or carrying heavy objects, and twisting/rotating the low back. For cervical discs, imbalanced forward head postures, as well as extension, and same-side lateral flexion and same-side rotation postures should be avoided.

Strengthening the paraspinal extensor musculature for a lumbar disc and neck extensors for a cervical disc is helpful. Strengthening core musculature of the low back, especially the multifidus, transversus abdominis, and pelvic floor musculature is also extremely important. Especially helpful for a lumbar disc problem is a progressive set of extension exercises. These exercises are known as McKenzie exercises, named for Robin McKenzie, the New Zealand physical therapist who popularized them. These exercises should progress from simply lying on the stomach, to passive spinal extension supported by the forearms, to active extension exercises.

Medical approach

The medical approach for a pathologic disc (disc bulge / herniated disc) depends on the severity of the condition. If neural compression is present, but is not severe, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication and physical therapy is usually prescribed. Steroidal anti-inflammatory medication or narcotic analgesic medication as well as cortisone injections are also possible. As a last resort, surgery can be performed.

Manual therapy case study

Joseph is a 52-year-old corporate executive who has been experiencing mild to moderate shooting pain down his right thigh and leg. He has already seen an orthopedist who ordered an MRI, which revealed a small right-sided posterolateral herniation at the L4-L5 level. Joseph has been going to physical therapy for the past month. Physical therapy consists primarily of spinal extension and core exercises. He reports that it is helping, but because it is entirely exercise-based with no hands-on care, he has come to a massage therapist because he would like some attention to his tight low back musculature. Joseph was also prescribed the analgesic, Vicodin, which he uses as necessary. Joseph weighs 170 pounds and is 5 foot, 8 inches tall.

The therapist performed passive straight leg raise (SLR) and slump test, which were positive on the right side for lower extremity referral. The therapist asked Joseph to perform cough test and Valsalva maneuver, which were negative. Joseph’s flexion range of motion was limited due to tightness in his low back. The end range of right lateral flexion elicited mild referral pain into the right leg. All other spinal ranges of motion were within normal limits. Palpation of lumbar extensor and gluteal musculature revealed marked tightness on the right side and moderate tightness on the left side. His hamstrings were also moderately/markedly tight bilaterally. Postural examination revealed that Joseph has an increased anterior pelvic tilt with a moderately increased lumbar lordosis.

The MRI findings definitively show that Joseph has a herniated nucleus pulposus (herniated disc). The massage therapist confirmed the degree of disc acuity by performing orthopedic assessment tests. Positive results with SLR and slump test, plus slightly increased referral with right lateral flexion show that the client’s disc is still somewhat acute, so the therapist knows that she must be careful with broad compression strokes that might move the vertebrae and stress the discs.

The focus of the therapist’s hands-on work was to relieve the tightness in the client’s low back, gluteal area, and hamstrings. This was done by using moist heat followed by soft tissue manipulation and gentle stretching. The therapist began with Joseph prone with a small pillow under his abdomen. A moist heat pack was placed on his low back for five minutes. The lumbar extensor musculature was then worked for 10-15 minutes with mild to moderate pressure, and focus on the right side. The therapist then spent 10-15 minutes working into Joseph’s gluteal and hamstring musculature.

Heat was reapplied for an additional five minutes and then the therapist stretched Joseph into flexion using first single knee to chest and then double knee to chest stretching, with careful attention that flexion did not increase his lower extremity symptomology. Any remaining time was spent on Joseph’s legs and thoracic region. In successive sessions, the therapist used contract-relax technique when performing the double knee to chest stretch. This approach was repeated twice per week for four weeks. In addition, the therapist counseled Joseph about which postures and activities he should avoid: especially prolonged sitting. The therapist recommended that he get up from his desk as often as possible and move around the office.

At the end of four weeks, Joseph felt as if his low back was much looser and freer, and his lumbar flexion range of motion was increased. He also felt as if the disc referral pain was mildly decreased. The therapist recommended that Joseph continue with massage for proactive maintenance care at a frequency of once each week.