Signs and Symptoms of Upper Crossed Syndrome

Anterior view of upper crossed syndrome, which involves hyperkyphotic thoracic spine, protracted shoulder girdles, and medially rotated arms. Permission: Joseph E. Muscolino.

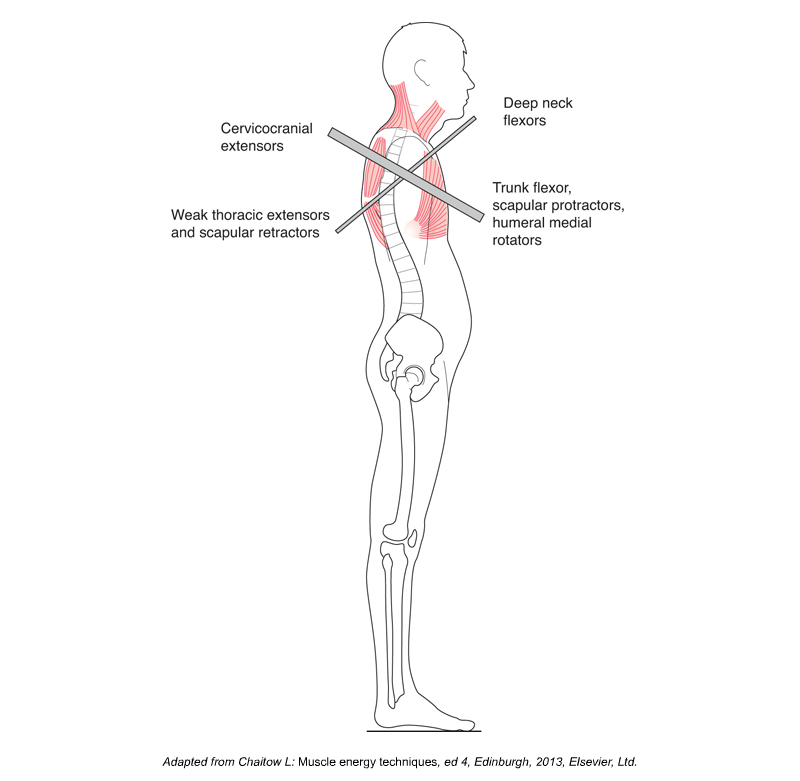

The first and most obvious sign of upper crossed syndrome (named by Vladimir Janda) is the characteristic postural dysfunction of protracted scapulae, medially (internally) rotated humeri, hyperkyphotic (overly flexed) upper thoracic spine, and a protracted (anteriorly held) head. Upon palpation, the following muscles will most likely be found to be tight: pectoralis major and minor, subscapularis, upper trapezius, levator scapulae, and sternocleidomastoid (SCM). And the client/patient will feel restriction of the following motions: retraction of the scapulae, lateral (external) rotation of the arms, extension of the upper thoracic spine, and retraction of the head. Efficiency of breathing will also become compromised because the postural collapse forward into thoracic flexion makes it more difficult to open the thoracic cavity and fill the lungs with air. This can be easily experienced. Assume the upper crossed syndrome posture and attempt to take in a deep breath.

Although pain is not necessarily a part of this condition, when this condition has existed for a long time, the client/patient does often experience upper back and neck pain, both due to the tightness of the upper trapezius and levator scapulae, and due to the accompanying imbalanced posture of the head that places increased stress on all the posterior extensor musculature of the cervical-cranial-thoracic region. If left unresolved for a long period of time, tension headaches also commonly accompany this condition.

Upper Crossed Syndrome. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3ed (Elsevier, 2017).

Assessment/ Diagnosis of Upper Crossed Syndrome

Assessment/diagnosis of upper crossed syndrome follows from the signs and symptoms of this condition. The most important assessment tool is static postural assessment, which will reveal the characteristic protracted scapulae, medially rotated humeri, hyperkyphotic upper thoracic spine, and an anterior head posture (hypolordotic lower cervical spine and a hyperlordotic upper cervical spine). Upon palpatory examination, tightness and the likely presence of myofascial trigger points (TrPs) will be found in the overly facilitated muscles listed above. As stated earlier, tightness (and often TrPs) are also commonly found in the pulled-long overly inhibited muscles as well. And, due to the associated anterior head posture, it is also common for myofascial trigger points to be found in the other posterior extensor musculature of the neck and head. Verbal history will likely reveal chronic “rounded” posture of the upper body, often due to work or other habits.

Upper crossed syndrome is a dysfunctional postural condition of the musculoskeletal system, so no further medical diagnosis/assessment is needed. However, if X-Rays are done, not only will the altered posture of the cervicothoracic spine be easily visualized on the lateral view, but the anterior wedging of the upper thoracic vertebral bodies will often also be visible in client/patients who have had this condition for many years.

Differential Diagnosis/Assessment of Upper Crossed Syndrome

Diagnosis/assessment of upper crossed syndrome is straightforward and simple; therefore no differential diagnosis/assessment is necessary. If the client/patient has the characteristic upper crossed posture, upper crossed syndrome can be assessed with confidence. However, this does not mean that the client/patient does not have the presence of additional conditions that should be assessed. The presence of any musculoskeletal condition, especially such a pervasive postural dysfunctional pattern like upper crossed syndrome that affects the entire upper body, often necessitates compensation patterns that can then create other conditions.