Signs and symptoms:

Piriformis syndrome causes compression upon the sciatic nerve; therefore it causes symptoms of sciatica, just as if the sciatic nerve were compressed by a pathologic disc or bone spur in the lumbar spine. (Note: Some textbooks refer to this symptomology as “pseudo-sciatica” because it is not sciatica caused by compression at the spine; however, sciatic compression is sciatic compression and should rightly be called sciatica, regardless of where the compression exists.) Sciatic nerve compression can cause sensory or motor symptoms into the lower extremity, primarily into the posterior thigh, leg or foot. Because piriformis syndrome involves a tight piriformis, this condition is also usually characterized by tightness and pain in the buttock. If the piriformis is tight enough, it might also affect the posture of the thigh, resulting in increased lateral (external) rotation of the thigh at the hip joint.

Assessment/diagnosis:

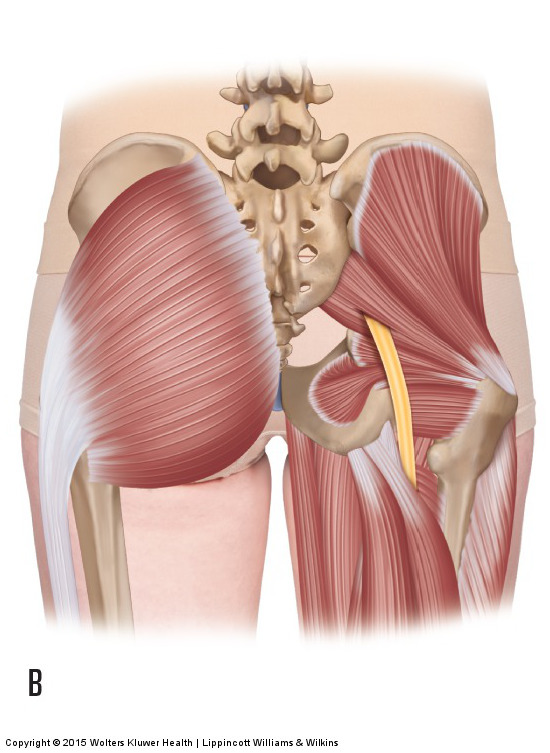

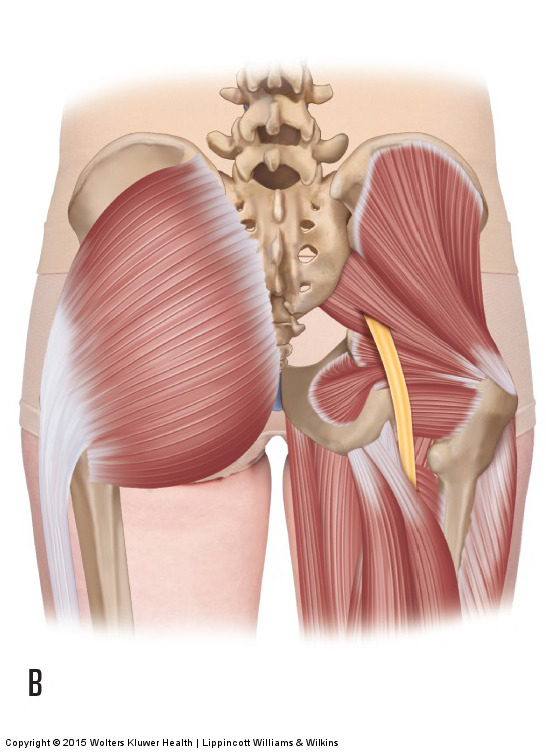

Common anomaly of the sciatic nerve passing through the piriformis muscle. Permission: Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach (2015).

There are two major facets to assessing/diagnosing piriformis syndrome. First, compression of the sciatic nerve is assessed by both clinical history and orthopedic assessment tests for sciatic compression. Second, the piriformis is determined to be the cause of the client’s/patient’s sciatica. It should be stressed that piriformis syndrome is not just the presence of a tight piriformis, but that the tight piriformis is compressing the sciatic nerve.

It should be first determined that the client/patient is experiencing sciatica referral symptoms into the lower extremity. During the verbal history, the client/patient should state that they are experiencing sensory or motor disturbance into the lower extremity; altered sensation (paresthesia) is most common. Orthopedic assessment tests are then performed to confirm compression of the sciatic nerve. These tests are straight leg raise (SLR), slump test, cough test, and Valsalva maneuver, as well as testing for lower extremity muscle strength by asking the client/patient to stand first on the toes and then on the heels.

Once it has been determined that the client/patient has sciatic nerve compression, piriformis tone must be assessed to see if it is possibly the cause of the compression. This can be done via palpation and also by assessing the piriformis muscle’s ability to lengthen by stretching it. The piriformis is palpated between the middle of the sacrum and the greater trochanter of the femur. With the client prone and the leg flexed at the knee joint to 90 degrees, palpating in this location, have the client/patient laterally rotate the thigh at the hip joint against your resistance by having them press their distal leg medially against your hand. Once the piriformis has been accurately located, have the client/patient relax and palpate it for tightness and pain. If the piriformis is tight or painful upon palpation, this does not confirm that the piriformis is necessarily the cause of the client’s/patient’s lower extremity sciatica; however it does make it more likely that the piriformis is involved. If palpation were to reproduce the characteristic lower extremity referral symptoms, this would confirm that the piriformis is the cause (or a cause) of the sciatica.

Length assessment of the piriformis can be done by laterally rotating the flexed thigh (note: when the thigh is flexed to approximately 60 degrees or more, the piriformis becomes a medial rotator, therefore lateral rotation will lengthen and stretch it). This stretch is often called the “Figure 4 stretch.” The piriformis can also be stretched by horizontally adducting the thigh at the hip joint. Similar to palpation assessment, tightness of the piriformis determined by length assessment stretching does not confirm that it is the cause of the client’s/patient’s sciatica symptoms, but it does increase the likelihood that the piriformis is involved. More definitive causality would be determined if stretching the piriformis directly reproduces the client’s/patient’s symptoms of sciatica.

As stated, determining the piriformis to be tight with palpation and stretching does not necessarily implicate the piriformis as the cause of the client’s/patient’s sciatica. It is extremely common for the client/patient to have sciatica due to another cause and to also have a tight piriformis. However, if the client’s/patient’s sciatica symptoms are directly reproduced when the piriformis is palpated and/or stretched, causality of the tight piriformis and piriformis syndrome can be more confidently determined. Short of this, if the client/patient is found to have a tight piriformis and no other cause for their sciatica symptoms have been found, then treatment should proceed on the assumption that the client/patient does have piriformis syndrome. Definitive assessment of piriformis syndrome can then be made if this treatment results in improvement of their sciatica symptoms.

Note: Because the piriformis is so often tight to stabilize the sacroiliac joint, whenever a tight piriformis is found, it is important to also assess the health of the sacroiliac joint.

Differential diagnosis:

Because piriformis syndrome causes symptoms into the lower extremity, it must be differentially assessed from all other conditions that refer into the lower extremity. These conditions include a pathologic disc or bone spur (space-occupying lesion / nerve impingement) of the lumbar spine, as well as myofascial trigger point referral into the lower extremity. It is also possible for symptoms into the lower extremity to be caused by a local condition of the lower extremity but to be incorrectly assessed as being referred from the lumbar spine or pelvis. Note: Piriformis syndrome should also be differentially assessed from a piriformis muscle that is tight but not compressing the sciatic nerve. If the latter condition is present and the client/patient is experiencing lower extremity referral, then another condition is causing the referral and should be investigated and assessed.