Note: This blog post article is the eighth in a series of twelve articles on musculoskeletal conditions of the low back (lumbar spine) and pelvis. For the rest of the articles in the series, scroll to the end of this article.

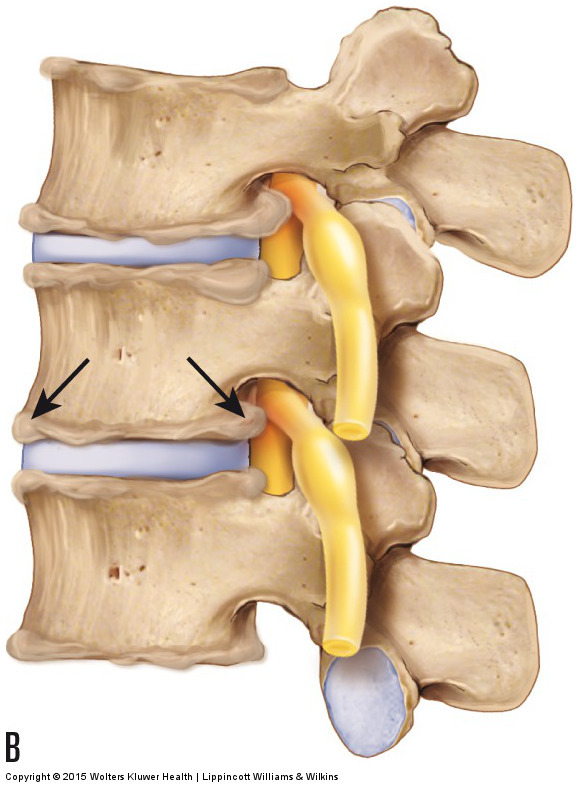

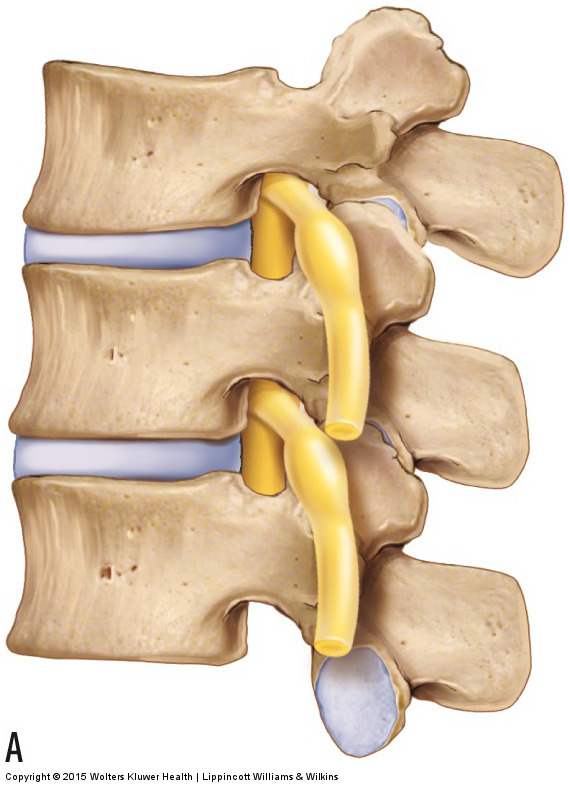

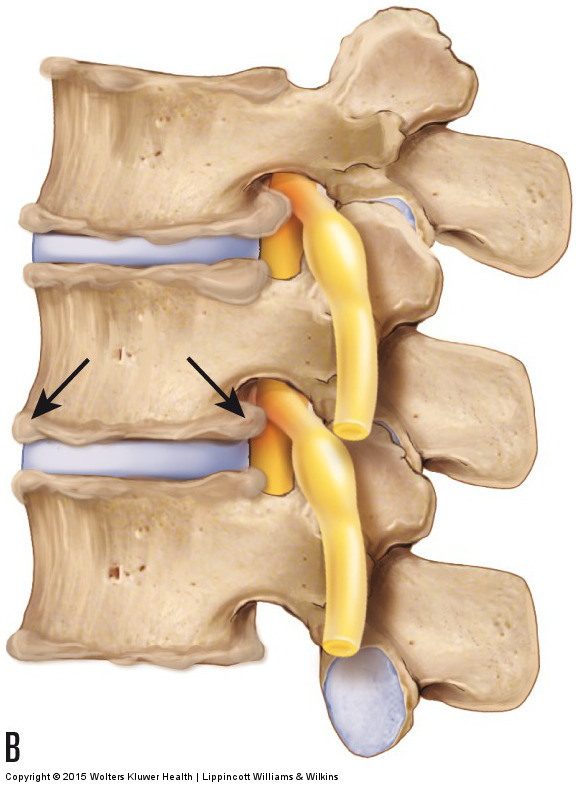

Figure 17. DJD and bone spur formation. (A) Healthy spine. (B) Bone spurs along the joint margins. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach. 2015.

Degenerative joint disease (DJD) is a disease in which the joint surfaces of bones deteriorate. DJD is a normal response to the physical forces that are placed on the joints as you age. However, if the degree of progression is either more than is typical for the client’s age or impairs function, it is considered a pathologic disease process. DJD is also known as osteoarthritis (OA); when this condition occurs in the spine, it may also be called spondylosis. Most older middle-aged and elderly clients who state that they have “arthritis” have DJD.

Note: The Terms Degenerative Joint Disease and Osteoarthritis

Arthritis literally means “joint inflammation” (“arthr” means joint; “itis” means inflammation). The term degenerative joint disease is gradually replacing the term osteoarthritis because inflammation is rarely involved in this condition, making the suffix “itis” inappropriate. Inflammation is usually present only when the condition has progressed and is more severe.

Description of Degenerative Joint Disease

The beginning stage of DJD involves breakdown of the articular cartilage that covers the joint surfaces of the two bones of the joint. As the condition progresses, calcium is deposited within the bone that underlies the articular cartilage (subchondral bone). In the later stage of DJD, calcium deposition begins to occur on the outer surfaces of the bones of the joints, and bone spurs (also known as osteophytes) protrude at the joint margins (Fig. 17). DJD can affect both the disc and facet joints of the spine. These bone spurs are easily seen on radiography, making radiographic analysis (x-ray) the best and easiest means to assess DJD.

Because DJD occurs as a result of accumulated physical stresses, radiographs of most middle-aged people will reveal at least some lumbar spinal DJD. Most of the time, the presence of DJD is an incidental finding, and the condition causes no symptoms. However, if the condition progresses to the point of functional impairment, a decrease of motion can occur at the joint where the DJD is present. This is a result of the presence of bone spurs that block full range of motion of the affected joint. Furthermore, if the calcium deposition creates bone spurs that are large enough to encroach on the spinal nerve in the intervertebral foramen or on the spinal cord within the spinal canal, the calcium deposition can cause compression of nervous tissue, resulting in referral into the lower extremities. When the calcium deposits of DJD cause compression of a spinal nerve or the spinal cord, DJD is similar in mechanism to a bulging or ruptured disc in that it is a space-occupying lesion that compresses nerve tissue.

Mechanism and Causes of Degenerative Joint Disease

The mechanism of DJD is a simple wear and tear response of the cartilage and bony surfaces of a joint resulting from the physical stress that is placed on the bones at the joint. If the degree of physical stress is more than the joint can absorb, the articular cartilage begins to degrade, and in so doing, more stress is transmitted to the subchondral bone. Excessive stress on the subchondral bone then causes calcium to be deposited along the margins of the bones of the joint, a physical process known as Wolff’s law. Wolff’s law states that calcium is deposited in response to the physical stress that is placed on a bone. This process is meant to strengthen bone by increasing its calcium mass; however, if the stresses placed on the bone are excessive, excessive calcium deposition occurs, resulting in bone spurs, as described previously. Movement and weight bearing are everyday microtrauma stresses that affect joints. Tight musculature, especially chronically tight postural muscles, can also be viewed as repeated microtrauma that adds compression forces to the joints that the tight muscles cross. Certainly, more powerful macrotraumas, such as falls and other traumatic injuries, can also greatly contribute to the progression of DJD.

(Note: Click here for a recent research article on Degenerative Joint Disease [Osteoarthritis]).

Note: Is Degenerative Joint Disease the Cause of the Client’s Pain?

DJD must be fairly marked in its progression to actually compress spinal nerves or the spinal cord and cause symptoms. However, physicians often wrongly blame DJD for a client’s pain when the pain is actually caused by tight muscles and other taut or irritated periarticular soft tissues located around the joint. Tight muscles are probably the most common aggravated periarticular soft tissue. When the physician orders and views radiographs (x-rays) of the client’s low back, if any DJD is present, as is usually the case in most middle-aged and older adults, it is often blamed for the client’s pain. But the muscles and other soft tissues are not visible on radiographs, and these tissues often are the real culprit. When this is the case, the manual therapist can provide an important service by relaxing, softening, and loosening the muscles and other soft tissues of the low back and pelvis. Further, because tight muscles and other soft tissues can add to the physical stress on joints, improving the health of the soft tissues can also decrease the progression of the client’s DJD and possibly even help to keep it from causing nerve compression.

Note: Treatment Considerations in Brief for Degenerative Joint Disease

Massage can be extremely beneficial in helping to decrease the muscular spasms that often coexist with and increase the physical stresses that foster DJD. Stretching is also helpful for the taut soft tissues that likely exist. However, if the DJD is advanced to the point that it is causing neural compression, then the client should not be laterally flexed to the side of a bone spur or placed in any position that causes or increases referral of symptoms into the lower extremity. If neural compression and/or nerve irritation is present, icing may help to decrease some of the accompanying inflammation.

This blog post article is the eighth in a series of twelve articles on musculoskeletal conditions of the low back (lumbar spine) and pelvis.

The articles in this series are:

- Hypertonic / tight muscles

- Myofascial trigger points

- Joint dysfunction

- Sprains and strains

- Sacroiliac joint injury

- Pathologic disc conditions and sciatica

- Piriformis syndrome

- Degenerative joint disease (DJD)

- Scoliosis

- Lower crossed syndrome

- Facet syndrome

- Spondylolisthesis