Lumbodorsal Fascia and Pain

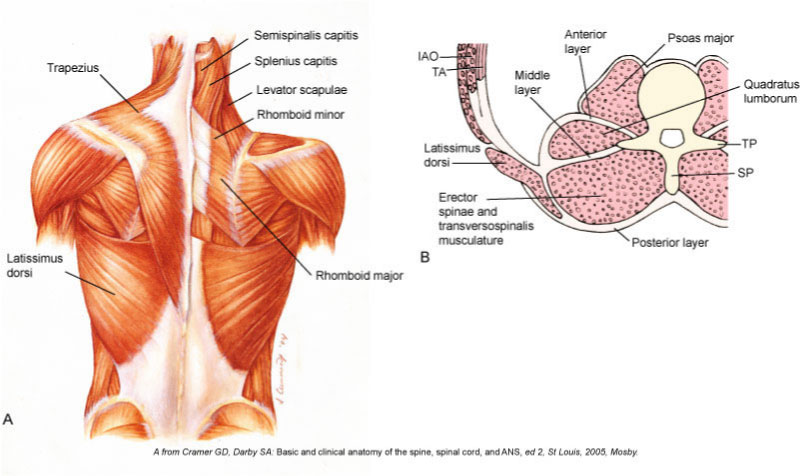

Lumbodorsal (Thoracolumbar) Fascia. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3ed. 2017 (Elsevier)

In the past few years, the lumbodorsal (thoracolumbar) fascia has been proposed as one of possible sources of “idiopathic low back pain” (pain that is stated as having no known cause). Authors Jan Wilke, Robert Schleip, Werner Klinger, and Carla Stecco wrote a review in Biomed Research International investigating the possible role of the lumbodorsal fascia in patients with low back pain, with special focus on combining findings from histological studies and experimental research.

From published research, the authors found that:

- In histological studies, the lumbodorsal fascia of both rodents and humans has been found to be densely innervated with nociceptive afferent pain fibers. Chemical stimulation of the lumbodorsal fascia has been shown to elicit severe and particularly long-lasting sensitization processes. These studies indicate that the lumbodorsal fascia exhibits a clear nociceptive neural capacity and therefore may be a source of pain in some cases of low back pain.

- In terms of morphological changes, the ultrasound examination by Langevin et al. demonstrated a reduction in shear-strain transmission in the lumbodorsal fascia of chronic low back pain patients compared with healthy controls. It seems plausible that this change could be explained by tissue adhesions induced by previous injury or inflammation. In addition, immobility or inactivity represents another factor potentially causing decreased shear-strain due to the thixotropic behaviour of hyaluronic acid between the layers. Hence, it is well possible that the tissue alterations represent the result of a sedentary reduction in everyday lumbar movements in low back pain patients. However, these findings cannot answer the question whether the observed tissue changes are a cause or a consequence of low back pain.

- Several in vivo examinations indicate that after mechanical, chemical, or electrical stimulation of the lumbodorsal fascia, the nervous system seems to respond with a particularly strong and long-lasting sensitization of dorsal horn sensory neurons. Assuming a proneness to overloading, microinjuries, and/or inflammation, it might be inferred that such tissue irritations could trigger substantial nociceptive pain adaptations which are frequently observed in patients with idiopathic back pain.

The authors further proposed three possible mechanisms for fascia-mediated low back pain sensations:

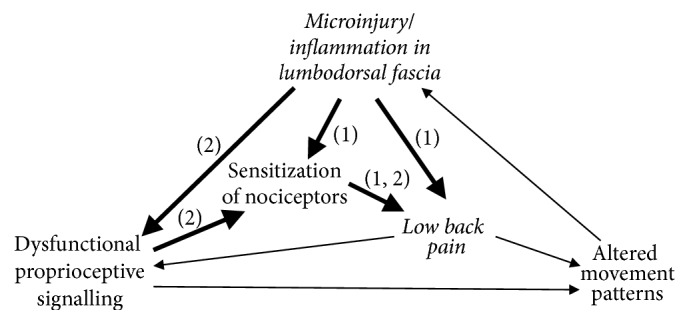

(1) microinjuries irritating nociceptive nerve endings in the lumbodorsal fascia may directly induce back pain (See Figure 1)

Figure 1. Two of several possible scenarios in respective cases of fascia-generated low back pain. (1) Microinjuries and/or inflammation and resulting irritation of nociceptive pain nerve endings in lumbar fascia may directly induce back pain, accompanied by a sensitization of fascial nociceptors. (2) tissue deformation due to immobility and/or injury may impair proprioceptive signaling. This induces a sensitization of fascial nociceptors, which then alters the functioning of related neurons in the spinal cord to respond more strongly to potential nociceptive signaling, even mild stimulation. (From Wilke et al., 2017)

(2) tissue restructuring, for example following immobility, chronic overloading, or microinjury, may compromise proprioceptive signalling, which by itself could decrease the pain threshold by means of an activity-dependent sensitization of wide dynamic range neurons (Figure 1)

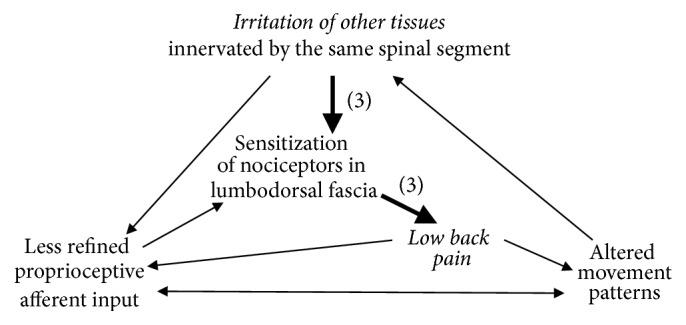

Figure 2. In a third scenario for fascia generated low back pain (3), irritation of other tissues—such as muscle fibers, facet joint capsules, spinal nerve roots, or the annulus fibrosus of the discs—could elicit an increased sensitivity in the lumbodorsal fascia innervated by the same segmental level of the spinal cord. The increased sensitivity of fascial nerve endings would then lead to nociceptive signaling, even in response to mild stimulation. (From Wilke et al., 2017.)

(3) nociceptive input from other tissues innervated by the same spinal segmental levels could elicit an increased sensitivity in the lumbodorsal fascia (Figure 2).

And, of course, various combinations of these three processes are possible.

Conclusion

All too often, the medical / allopathic world ignores the contribution of extra-articular myofascial tissues to low back and other pain and dysfunction syndromes. Consequently, if no osseous structural damage is found on radiographic examination (x-ray) and no annular disc damage is seen on MRI examination, the patient’s / client’s pain is often described as idiopathic, in other words pain from an unknown origin (the word root “idio” comes from the same origin as the word “idiot”, in other words, not knowing). Myofascial dysfunction is essentially impossible to diagnose/assess without direct manual and movement assessment techniques such as soft tissue palpation and stretching length assessment. For this reason, medical practitioners usually miss myofascial dysfunction. Instead, manual therapists are ideally suited to assess myofascial dysfunction.

Comments added by Robert Schleip

Note: This blog post article was created in collaboration with TerraRosa.com.au.

(Click here for a blog post article: Can manual therapy alter the thoracolumbar fascia?)