As with the muscles, it is also helpful to know the ligaments of the cervical spine to be able to effectively stretch the client’s neck. Whatever technique is used, the purpose of stretching is to loosen all soft tissues that are taut and restricting joint motion. Even though the function of a ligament is to stabilize and limit motion of the bones to which it attaches, a taut ligament can be just as culpable as a tight muscle in excessively restricting the motion of a joint. Therefore, when a client presents with a tight neck, a basic knowledge of the ligaments of the neck is valuable.

As with the muscles, it is also helpful to know the ligaments of the cervical spine to be able to effectively stretch the client’s neck. Whatever technique is used, the purpose of stretching is to loosen all soft tissues that are taut and restricting joint motion. Even though the function of a ligament is to stabilize and limit motion of the bones to which it attaches, a taut ligament can be just as culpable as a tight muscle in excessively restricting the motion of a joint. Therefore, when a client presents with a tight neck, a basic knowledge of the ligaments of the neck is valuable.

Note: When intrinsic fascial tissue of a joint (the ligamentous / joint capsule complex) is excessively taut, the manual therapy treatment technique that can efficiently address this is joint mobilization (whether it is Grade IV “arthrofascial stretching” joint mobilization, or is Grade V “chiropractic fast thrust” joint mobilization, also known as joint manipulation or an adjustment.)

Ligament Function – the “action” of a ligament…

The “action” of a ligament is similar to that of an antagonist muscle. If an antagonist muscle is tight, it restricts motion that is opposite that of its mover action(s). For example, if a neck extensor (located posteriorly) is tight, it restricts motion of the neck anteriorly into flexion. Because this motion is usually to the side of the body opposite the side on which the muscle is located, antagonist muscles are sometimes called contralateral muscles; contralateral literally means opposite side. Similarly, ligaments tend to be located contralaterally, on the other side of the joint from the direction of limited motion.

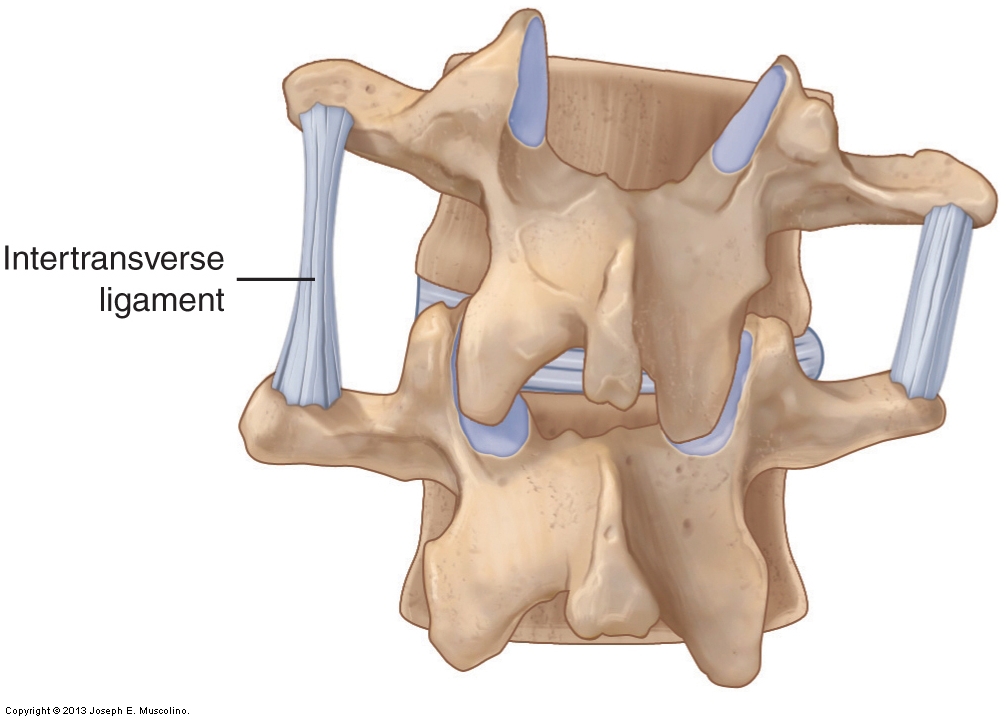

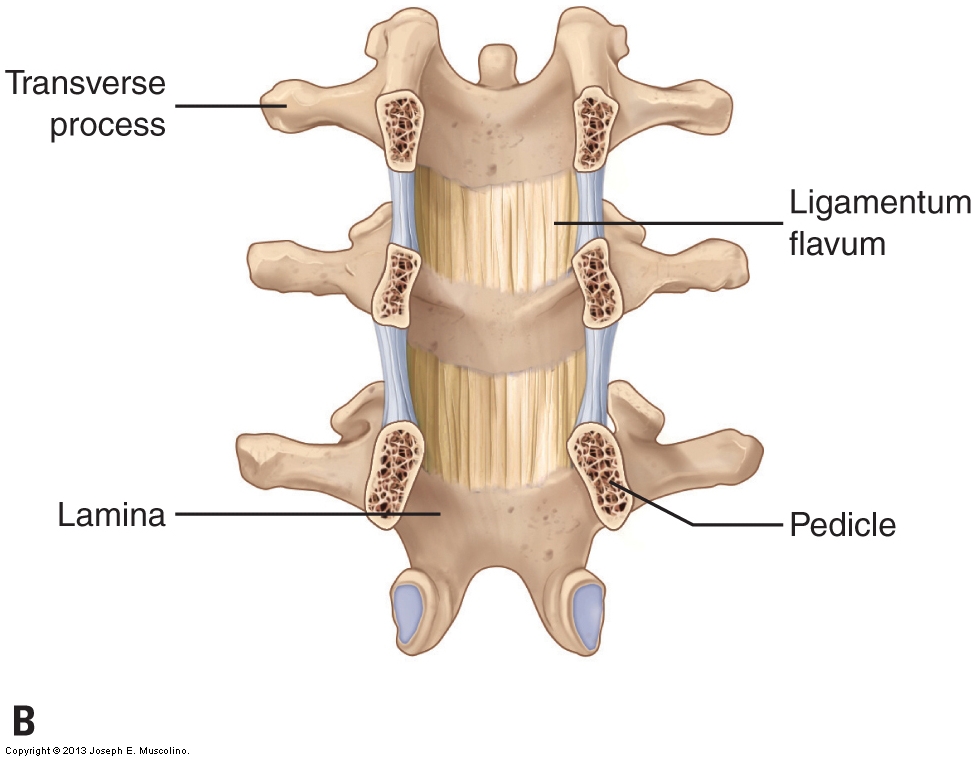

For example, if the neck resists moving into flexion, the taut ligaments that would restrict this motion are located posteriorly (where antagonist neck extensor muscles are located). If the motion that is limited is right lateral flexion of the neck, the taut ligaments limiting that motion would be located in the left side of the neck (where antagonist left lateral flexor muscles are located) (Fig. 11). As is typically the case, rotation is a bit trickier. Just as muscles that perform rotation may be on either side of the body in relation to the rotation they create, ligaments that restrict right or left rotation can also be located on either side of the body. Similar to musculature, determining a ligament’s role in restricting rotation can best be seen by looking at how the ligament (partially) “wraps” around the body part in the transverse plane.

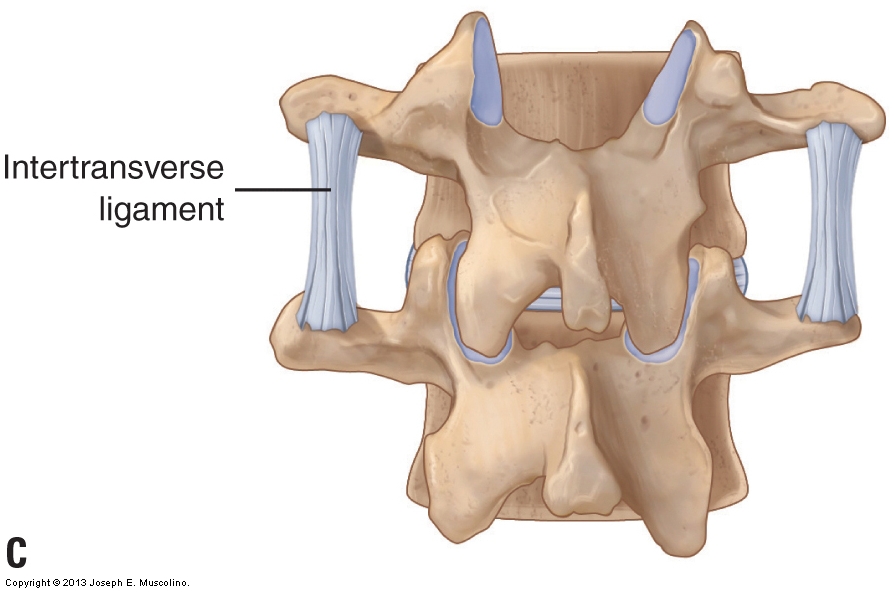

Figure 11. Ligament function. Posterior view of two vertebrae that illustrates how a ligament becomes taut and limits motion of the bones of a joint in the direction opposite the ligament’s location. In this example, when the superior vertebra right laterally flexes, the intertransverse ligament located on the left side becomes taut and limits this motion. (Courtesy of Joseph E. Muscolino.)

Major Ligaments of the Cervical Spine:

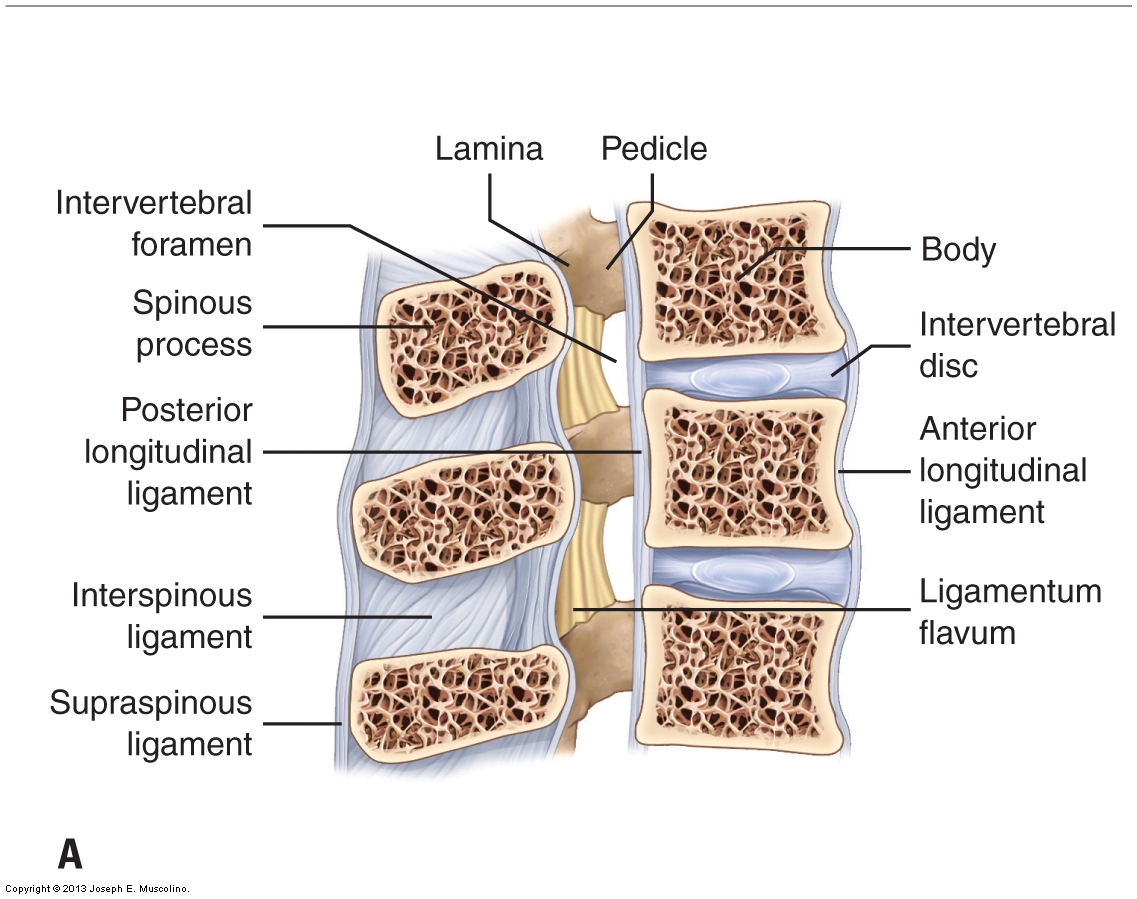

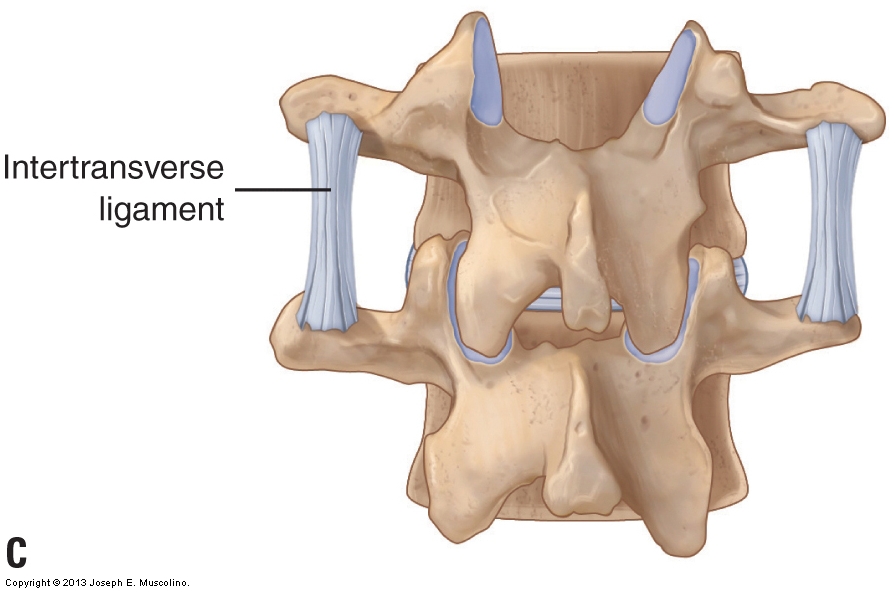

The major ligaments of the cervical spine are shown in Figure 12. The supraspinous ligament (thickened in the cervical spine as the nuchal ligament), interspinous ligaments, fibrous capsules of the facet joints (which are ligamentous in structure and therefore also function to limit motion), ligamentum flavum, and posterior longitudinal ligament are all located posterior to the axis of motion for flexion and extension of the spine; therefore, they all limit flexion. The anterior longitudinal ligament is located anterior to the axis of motion for flexion and extension of the spine; therefore, it limits extension. The intertransverse ligaments are located laterally. They limit lateral flexion to the opposite side of the body from where they are located (contralateral lateral flexion). Many of these ligaments also act to limit rotation of the cervical spine to one side or the other.

Figure 12. Ligaments of the spine. (A) Right lateral view of a sagittal plane cross section through the spine. (B) Anterior view of a frontal plane section through the pedicles of the spine in which the ligamentum flavum inside the spinal canal can be seen. (C) Posterior view depicting the intertransverse ligaments. (Courtesy of Joseph E. Muscolino.)

(All figure credits: Courtesy of Joseph E. Muscolino. Originally published in Advanced Treatment Techniques for the Manual Therapist: Neck. 2013.)

(Note: Click here for an article on the ligaments of the lumbar spine and pelvis.)

Note: This blog post article is the fifth in a series of six posts on the

Anatomy / Structure of the Cervical Spine for Manual Therapists.

The Six Blog Posts in this Series are:

- Introduction to the Cervical Spine

- Cervical Spinal Joints

- Motions of the Cervical Spine

- Musculature of the Cervical Spine

- Ligaments of the Cervical Spine

- Precautions When Working the Neck