The concept of muscle memory is vitally important in the world of manual and movement therapy. Yet, there seems to be some controversy about what it is and how it works. To better understand this idea and its application to clinical work, let’s explore the concept of muscle memory.

Simply put, muscle memory describes the idea that the musculature of the body contracts in patterns, for both posture and motion of the body. And these patterns reside in the nervous system and are on some level memorized, working without our conscious control. Hence the term muscle memory.

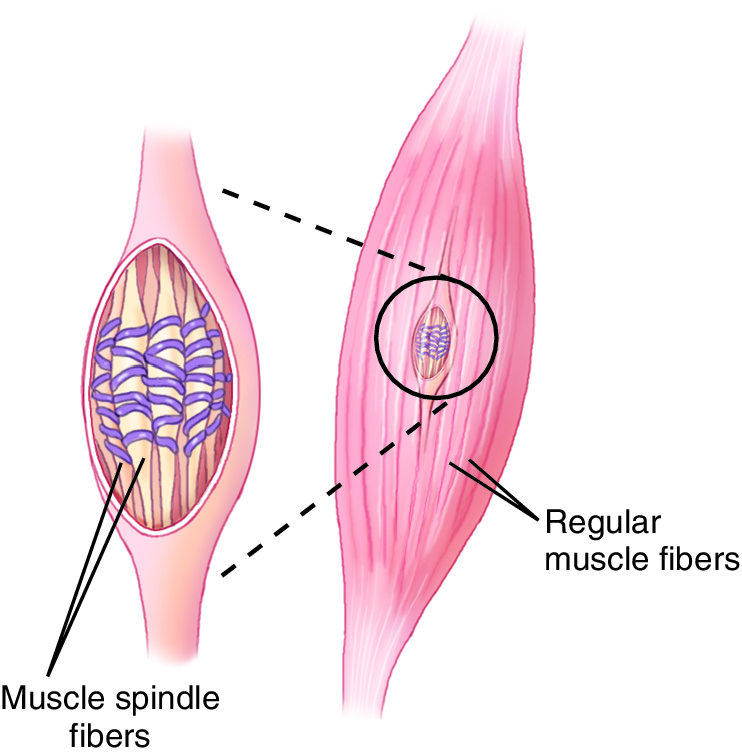

Figure 1. An analogy can be made between the entrenchment of neural patterns and the etching of water into the earth as it flows down a mountainside. Figure Courtesy Joseph E. Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3rd ed. (2017) Elsevier.

Regarding memorized patterns of muscle contraction for movement, there is little controversy. By practicing certain activities such as walking, swinging a tennis racquet, playing a piece of music on the piano, or driving a car while drinking a cappuccino and adjusting the radio dial, we learn to execute these complex and coordinated activities with little or no input from the part of the brain that controls voluntary willed muscle contractions, the cerebral primary motor cortex. Instead, once a movement pattern has been initially learned in the cerebral motor cortex, it is transferred to the basal ganglia, located deeper within the brain. Consequently, it is possible to execute a complex coordinated movement pattern while paying little or no attention to it and thinking of something else entirely. So, if the question asks: What is muscle memory for movement? The answer would be that it is a stored memorized posture or movement pattern that can be released from the basal ganglia of the brain. And the more we practice these movement patterns, the more entrenched these neural patterns become. An analogy could be made to water running down a mountainside, gradually etching itself deeper and deeper into the ground as repetition and time continue (see Figure 1 above).

More controversial and more relevant to the world of manual and movement therapy is how the concept of muscle memory relates to posture. The posture of our body is largely determined by the memorized pattern of baseline tone of the musculature of our body (the occurrence of fascial adhesions is another factor that affects postural patterns). By exerting pull upon the bones and joints, resting baseline muscle tone determines the position, hence posture of our body. Indeed, when clients come in to a manual therapist, their usual complaint is that their resting baseline tone of musculature is too tight. Musculoskeletally, the most common goal of soft tissue manipulation (massage therapy) is to change the muscle memory of baseline resting tone of the tight muscles of our clients.

So, let’s explore the idea of muscle memory in this context. The first misconception is the belief that postural muscle memory resides in muscle tissue itself. The muscular system is an amazingly complex and awe-inspiring system of the body, but it does not hold the key to its own memory. Certainly, adhesions present within musculature can determine its ability to stretch, and therefore affect its degree of passive tension and therefore the posture of the body. But if we are referring to active muscle tone, in other words, muscle contraction, the memory for that resides elsewhere. This can be easily understood by considering a person who has suffered a traumatic injury that severs the lower motor neurons (LMNs) that synapse with and control a muscle. In these cases, the muscle will become flaccidly paralyzed and will have no ability to contract (unless electrical stimulation is applied from the outside). If the memory for the muscle contraction were actually within the muscle, then it would be able to contract, even if its nerve were not functioning.

So where does muscle memory for baseline resting tone reside? Similar to muscle memory for movement patterns, it resides in the nervous system. The nervous system is the grand master controller of all muscular function. However, instead of being located in the basal ganglia, it is located in a different region of the brain known as the gamma motor system.

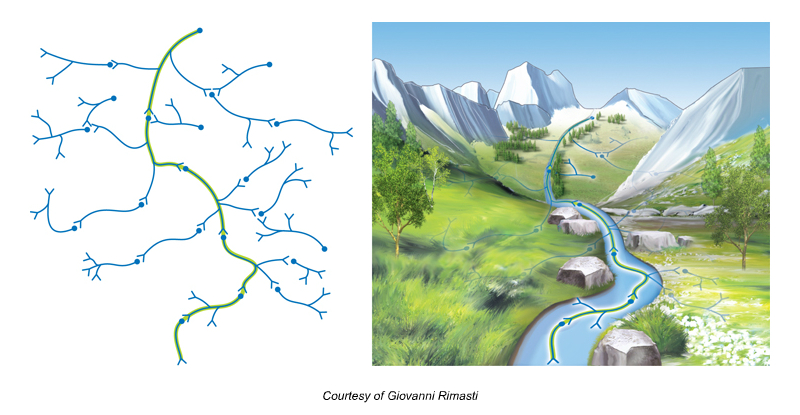

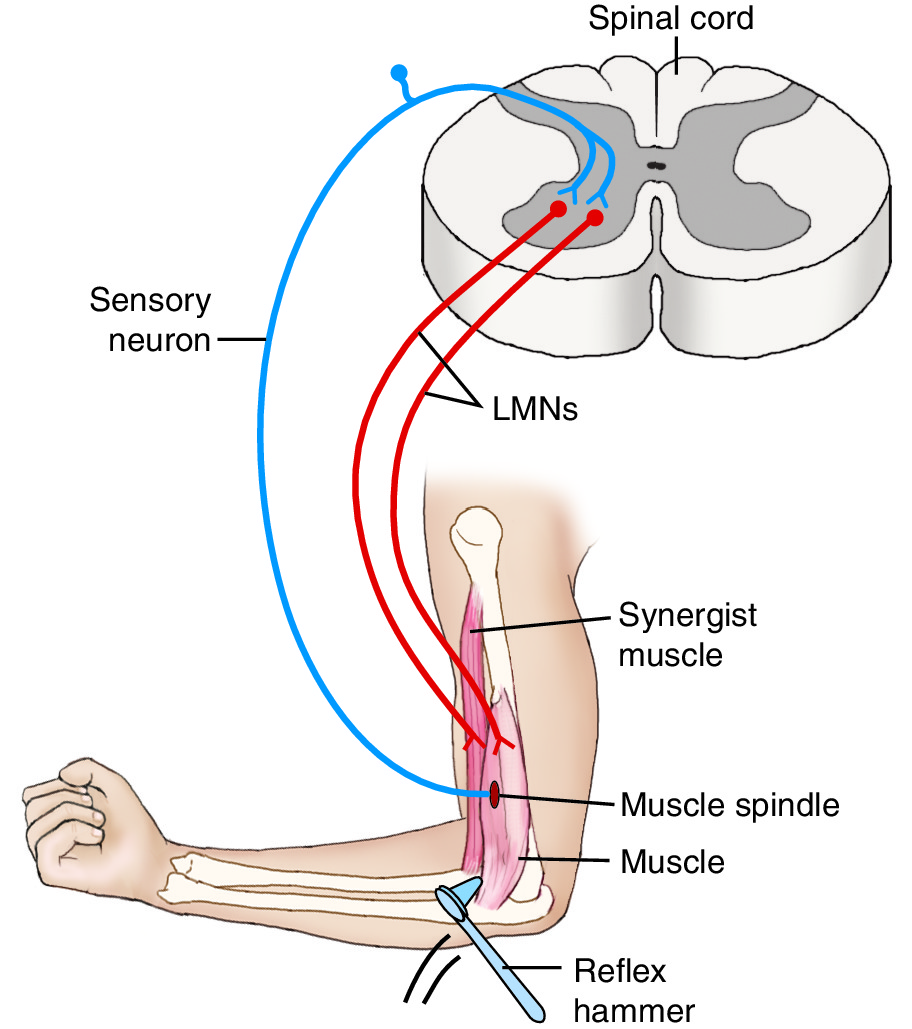

The manner in which the gamma motor system of the brain controls resting muscle tone is via muscle spindle fibers. Muscle spindle fibers are specialized muscle cells that are sensitive to stretch. They are located within the belly of the muscle, lying parallel to the regular muscle fibers (Figure 2). When the muscle is either stretched too long or stretched too quickly the muscle spindle fibers are stimulated and they send an impulse within sensory neurons into the spinal cord. These sensory neurons synapse with LMNs and cause them to send a signal for contraction to the regular muscle fibers of the muscle and its synergists (Figure 3). When the muscle contracts toward its center, it is no longer stretched and therefore cannot be overly stretched and torn. For this reason, the muscle spindle reflex, also known as the stretch reflex, is viewed as a protective reflex that prevents musculature from being overly stretched and torn.

Figure 2. Muscle spindle fibers are a specialized type of muscle cell. They are located within a muscle and lie parallel to the regular muscle fibers. Figure Courtesy Joseph E. Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3rd ed. (2017) Elsevier.

Figure 3. Cross section of the spinal cord and the muscle spindle stretch reflex. The muscle spindle reflex is triggered to occur when the muscle is either stretched too far or stretched too quickly, as when stretched too quickly by being hit with a reflex hammer as shown. This reflex causes lower motor neurons (LMNs) to direct the muscle and its antagonists to contract. Figure Courtesy Joseph E. Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3rd ed. (2017) Elsevier.

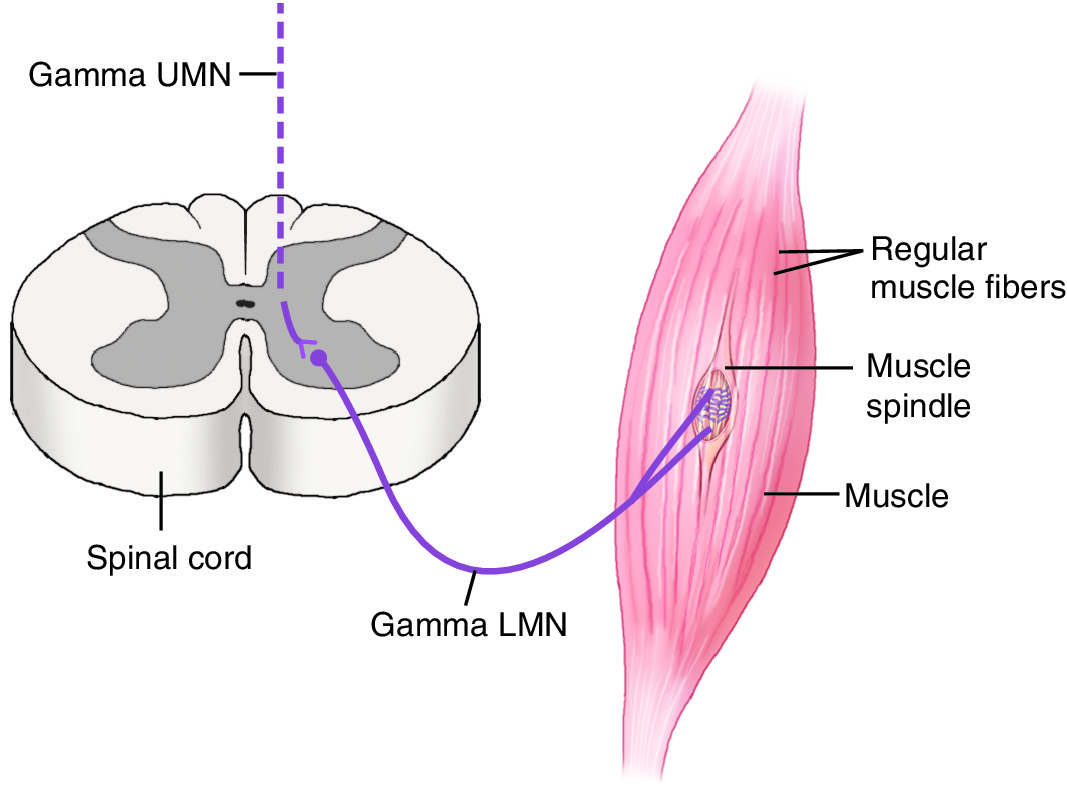

The critical aspect of this mechanism is that the sensitivity of the muscle spindle fibers can be set by specialized LMNs known as gamma LMNs. These in turn are controlled by gamma upper motor neurons (UMNs) that are located within the brain and operate subconsciously (Figure 4). When this gamma motor system of the brain orders the muscle spindle fibers to contract and shorten, they become less tolerant to being stretched and therefore more apt to trigger the muscle spindle stretch reflex. The stretch reflex will then cause the muscle to contract and tighten to match the tone of the spindle fibers within it. On the other hand, if the gamma motor system does not contract the muscle spindle fibers, then they will be longer and more tolerant to being stretched, and less likely to trigger the stretch reflex. As we move our bodies with normal activities of daily life, we inevitably stretch our muscles to some degree because when we order a muscle on one side of a joint to contract and shorten to cause movement, its antagonists on the other side of the joint must lengthen and stretch to allow this movement to occur. If and when this stretch exceeds the tolerance of the muscle spindle fibers, they will trigger the stretch reflex to occur. Hence, resting muscle tone comes to mirror the tone of the muscle spindle fibers. In this manner, muscle spindle tone determines the muscle memory of resting baseline muscle tone in our body.

Figure 4. Cross section of the spinal cord and muscle spindle fibers within a muscle. The sensitivity of muscle spindle fibers to stretch is determined by gamma lower motor neurons (LMNs) that direct the muscle spindle fibers to contract and shorten. These gamma LMNs are controlled by gamma upper motor neurons (UMNs) that originate in the brain. Figure Courtesy Joseph E. Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3rd ed. (2017) Elsevier.

Thus, when we are working on a client’s tight muscle, what we are really trying to accomplish is to lower the gamma motor system activity so that the muscle spindle fibers will relax, allowing the regular fibers of the muscle to relax. (It should be noted that this is not true of trigger points, which are primarily a local phenomenon.) We may be working directly on the muscle, but we do so to affect its gamma spindle activity in regions of the brain that act unconsciously. In effect, we are trying to alter the patterns of spindle tone that have been set. Whether this pattern has been in place for months, years, or even decades, is critically important. As a general rule, it is the chronicity, not severity, of a tight muscle that is the primary factor that determines how long it takes to loosen a client’s musculature. Put simply, when it comes to changing muscle memory for tight muscles, the purpose of massage, as well as stretching, is to alter gamma motor activity of the brain so that we can change muscle spindle tone, and thereby change resting muscle tone.

(Click here for a blog post article on neural plasticity.)

Note: This blog post article is modified from the original article published in the massage therapy journal (mtj), spring, 2009 issue.