Pathologic discs of the lumbar spine are extremely common. Often they compress the sciatic nerve resulting in sciatica. Although any pathologic disc is potentially serious, the degree of symptoms and functional impairment can vary tremendously. Some pathologic discs require immediate surgery, whereas others cause no problem and may be found, if at all, only incidentally when magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or a computed tomography (CT) scan is done for another reason.

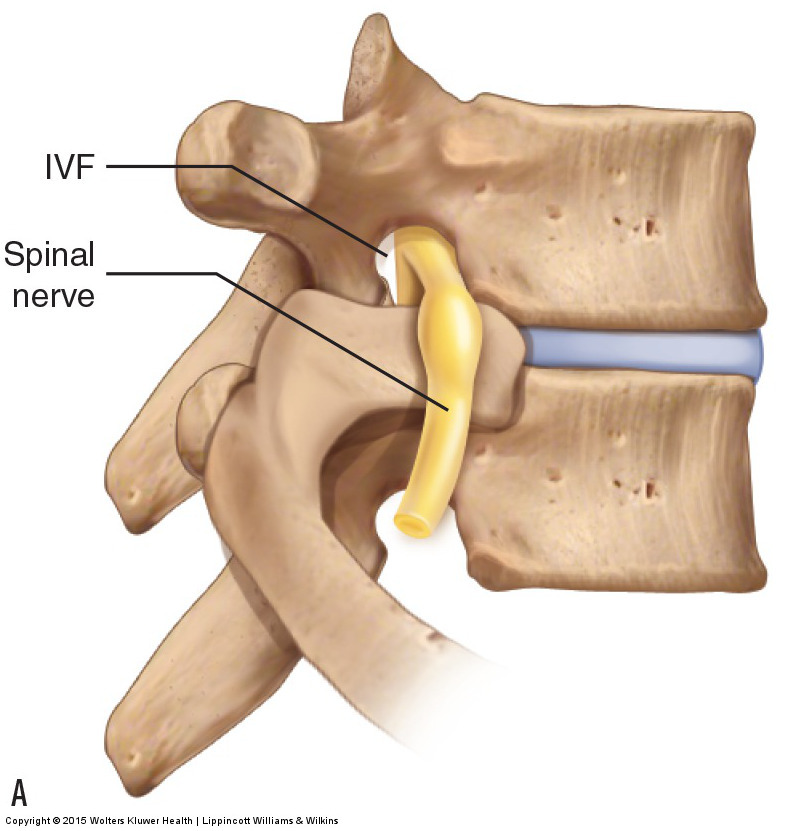

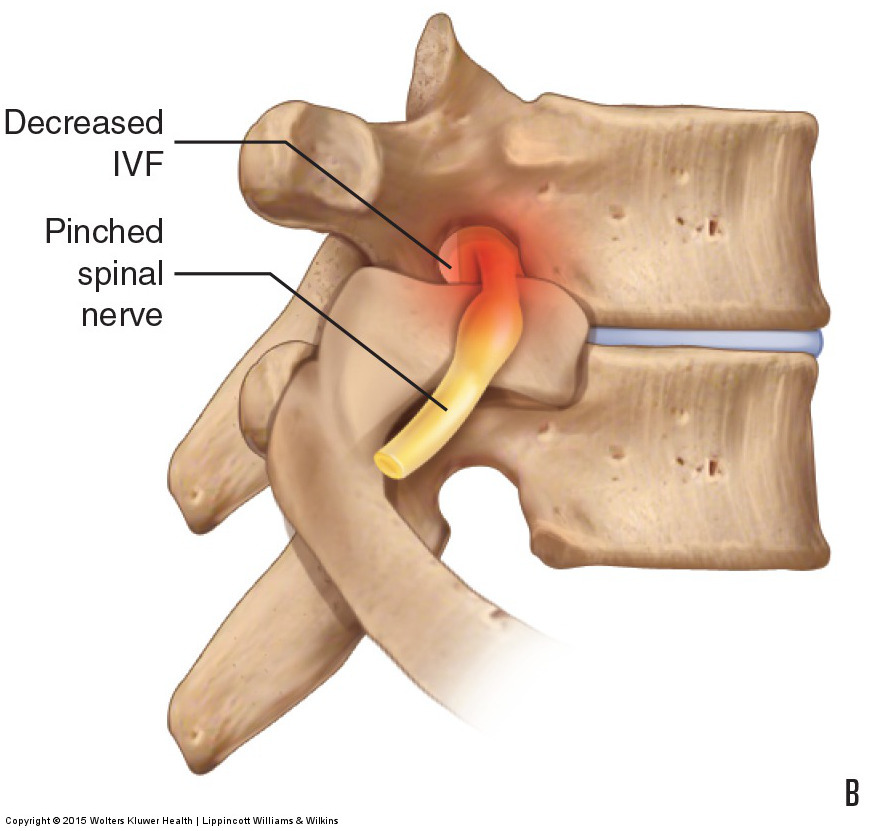

Figure 11. Disc height and the size of the intervertebral foramen. (A) The disc is healthy and there is a normal-sized intervertebral foramen (IVF) through which the spinal nerve travels. (B) The disc has thinned, resulting in an IVF that is decreased in size and impingement of the spinal nerve. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach. 2015.

Note: This blog post article is the sixth in a series of twelve articles on musculoskeletal conditions of the low back (lumbar spine) and pelvis. For the rest of the articles in the series, scroll to the end of this article.

Description of Pathologic Disc Conditions

There are two major types of pathologic conditions of the intervertebral disc:

- Disc thinning

- Bulging or rupture of the fibers of the annulus fibrosus

Disc thinning involves a decrease in the height of the disc. Given that the volume of the inner nucleus pulposus determines the height of the disc, disc thinning occurs as the nucleus pulposus gradually desiccates with age. This condition usually occurs when the client is middle-aged or older. The danger of disc thinning is that as the two adjacent vertebrae approach each other, there is a decrease in size of the intervertebral foramina at that level through which the spinal nerves pass (Fig. 11). Because greater disc thickness allows for greater range of motion of that intervertebral joint, disc thinning can also result in decreased range of motion.

Figure 12. Disc height and the size of the intervertebral foramen. (A) The disc is healthy and there is a normal-sized intervertebral foramen (IVF) through which the spinal nerve travels. (B) The disc has thinned, resulting in an IVF that is decreased in size and impingement of the spinal nerve. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach. 2015.

Thus, if disc thinning becomes marked in degree, spinal nerve compression is possible. Because a spinal nerve carries both sensory and motor neurons, altered sensation can occur wherever the sensory neurons of that spinal nerve originated and/or altered motor function can occur wherever the motor neurons of that spinal nerve end. Sensory symptoms can include tingling, numbness, or pain; motor symptoms can include twitching, weakness, or flaccid paralysis of the musculature. Because the lumbar and sacral spinal nerves innervate the lower extremity, these symptoms occur in the pelvic (gluteal) region, thigh, leg, and/or foot. Specifically, if nerve roots of the sciatic nerve are compressed, the client can experience sciatica. However, for most clients, disc thinning does not usually progress to the point that nerve compression with lower extremity referral occurs.

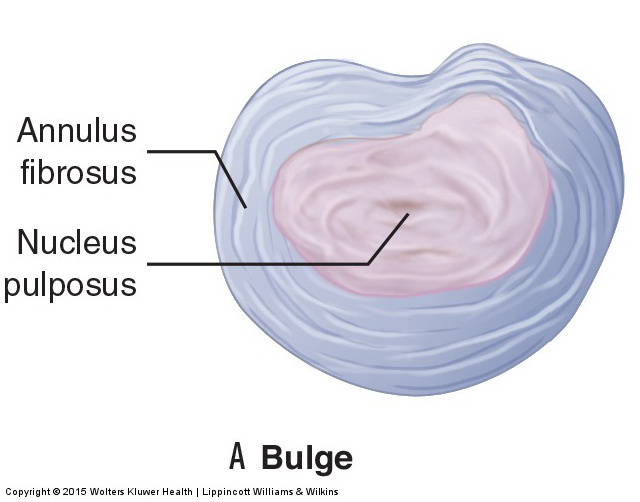

The other major type of pathologic disc condition is a weakening of the outer annulus fibrosus that leads to a bulging or rupture of its fibers. This condition has three major types/gradations of severity:

- Disc bulge

- Disc rupture

- Sequestered disc

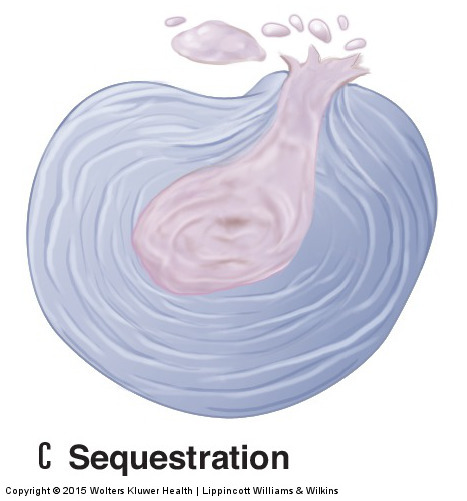

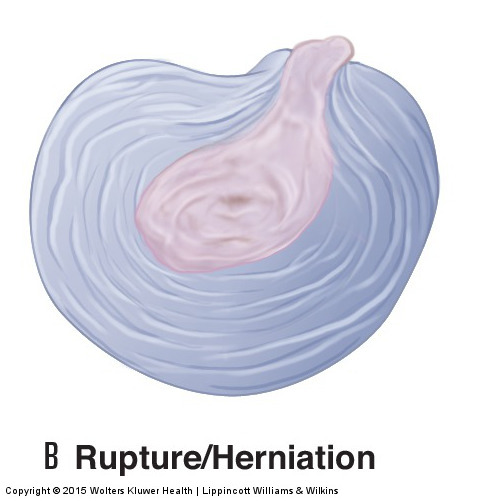

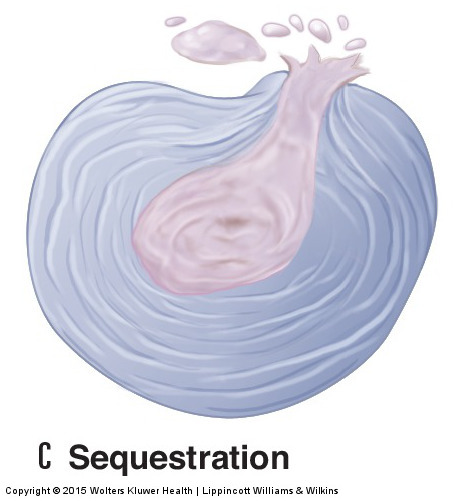

The mildest form is a disc bulge. In this condition, the annular fibers weaken and allow the nucleus pulposus to push against the annulus, causing it to bulge outward (Fig. 12A). A disc bulge is considered the mildest form because the annular fibers are still intact. A disc rupture is considered the next degree of severity because the annular fibers have weakened to the point that the pressure of the nucleus pulposus causes them to rupture. In this case, the nucleus pulposus can actually extrude through the annulus and enter into the intervertebral foramen or spinal canal. A disc rupture is also known as a disc herniation or disc prolapse (Fig. 12B). The third and most severe form of this pathologic disc condition is the sequestered disc. A sequestered disc is a disc rupture in which a portion of the nucleus pulposus that extrudes through the annular fibers separates from the inner core of nucleus pulposus (the term “sequester” literally means to set apart or separate) (Fig. 12C). It cannot rejoin the disc and is left to float within the intervertebral foramen or spinal canal.

The danger with disc bulges, herniations, and sequestrations is that the disc can push outward and compress the spinal nerve within the intervertebral foraminal space or the spinal cord within the central spinal canal at that level. Therefore, they are considered to be space-occupying lesions. (Note: DJD, covered later in this chapter, is another common example of a space-occupying lesion that can compress spinal nerves). With a bulging disc, the bulging annular fibers can compress the neural structures; with a ruptured or sequestered disc, the nucleus pulposus can create the compression.

If a pathologic disc compresses nerve roots of the sciatic nerve, a condition called sciatica can occur. The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve in the human body. It measures approximately a quarter inch in diameter and is composed of L3, L4, L5, S1, and S2 nerve roots. Symptoms of sciatica can be sensory and/or motor because both sensory and motor neurons are located in the sciatic nerve. Pain and/or motor weakness of sciatica can occur in the posterior thigh, or leg, or anywhere in the foot (Fig. 13).

Figure 13. The sciatic nerve provides sensory innervation into the lower extremity. Compression of the sciatic nerve can result in sciatica. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach. 2015.

The actual determinant of the severity of these conditions is the degree of nerve compression that occurs. For this reason, a large disc bulge can be much more problematic than a small disc rupture. Sequestered discs are usually the worst because the extruded fragment of nucleus pulposus remains in the intervertebral foramen or spinal canal and can continue to compress the spinal nerve or spinal cord, respectively.

Mechanism of Pathologic Disc Conditions

Annular bulges and ruptures occur as a result of forces that stress and weaken the annular fibers. These can be microtraumas or macrotraumas. Microtraumas are small physical stresses. One example is the everyday compression that results from supporting the weight of the trunk, neck, head, and upper extremities. Another example is holding a prolonged posture that stresses the disc, such as maintaining a bent-over posture of the trunk to work down in front of the body. Postures in which the trunk is held forward in flexion are especially prevalent and contribute to disc problems. The position of flexion pulls taut the posterior annular fibers while at the same time pushing the nucleus pulposus posteriorly against these taut fibers. Continual flexion postures cause eventual weakness and fraying of the posterior fibers of the annulus (Fig. 14). These microtraumas accrue over time and gradually weaken the annulus until the nucleus either causes it to bulge or ruptures through it.

Figure 14. Nucleus pressure against the posterior annular fibers. Flexion of a vertebral joint creates a compression force at the anterior disc that pushes the nucleus pulposus posteriorly against taut posterior annular fibers. Repeated flexion postures can lead to excessive wear against the posterior annulus. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach. 2015.

Macrotraumas such as severe traumatic sports injuries or falls may also cause discs to bulge or rupture. Often, a weakened disc from repeated postural microtraumas coupled with a somewhat traumatic event will cause the integrity of the fibers of the annulus fibrosus to fail, resulting in a bulge or rupture of its fibers.

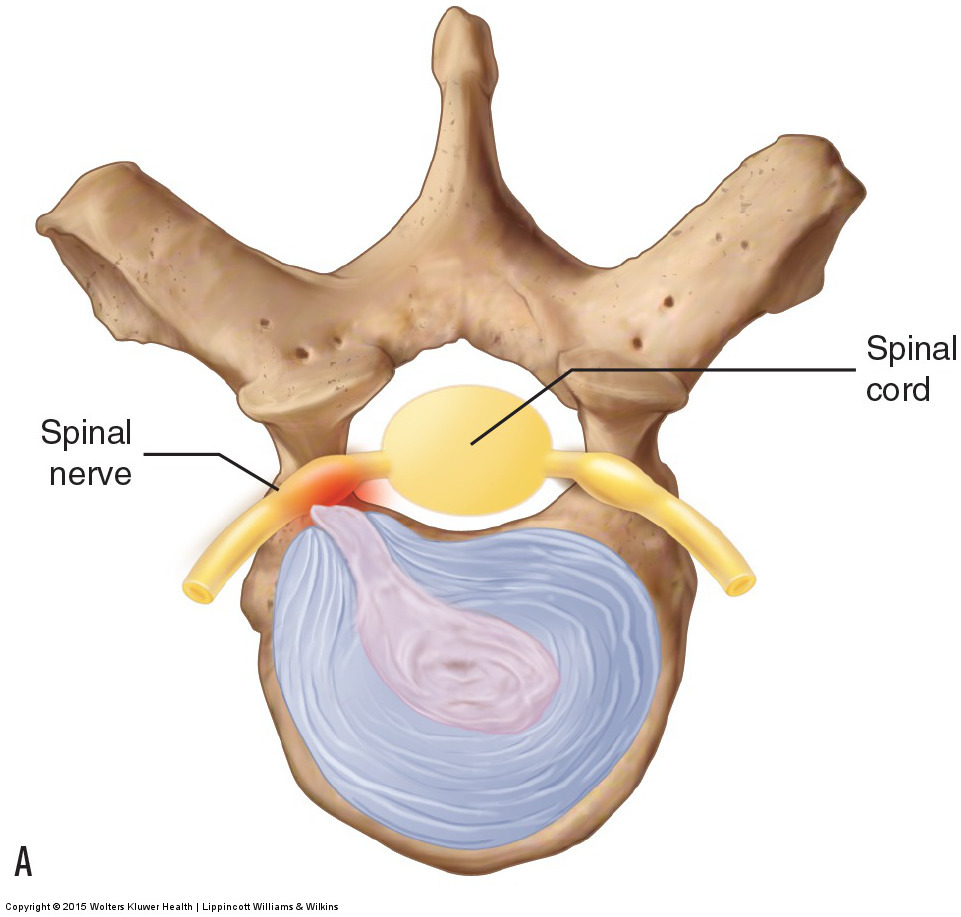

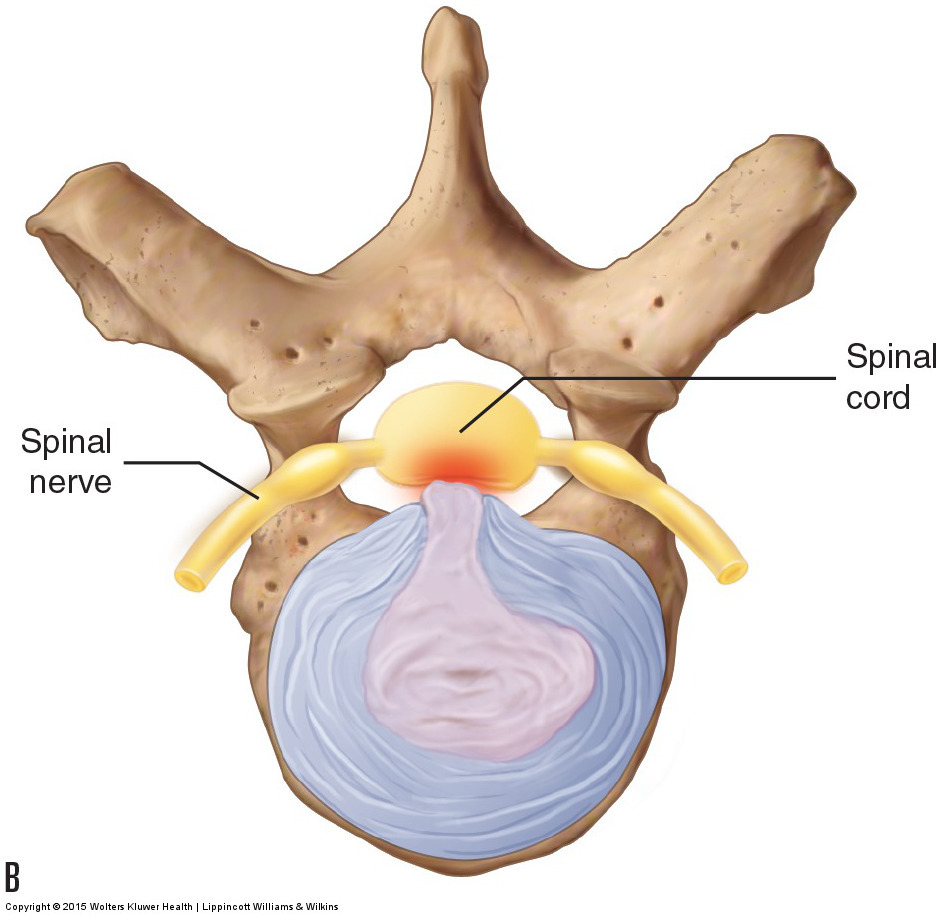

Most often, the annulus weakens and/or ruptures posterolaterally regardless of whether the pathologic disc occurs as a result of microtrauma or macrotrauma. The prevalence of flexion postures contributes to this problem because flexion causes the nucleus pulposus to push backward against the posterior annular fibers, gradually weakening them. However, because the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine reinforces the annulus midline posteriorly (posteromedially), the effect of the physical stress of constant and recurring flexion postures usually manifests posterolaterally. Because the intervertebral foramina are located posterolaterally, most disc conditions result in compression of a spinal nerve in the intervertebral foramen on one side. If a disc were to bulge or rupture in the midline posteriorly, it would compress directly on the spinal cord in the central spinal canal.

The symptoms of a lumbar disc bulge or rupture may refer to the lower extremity, occur in the low back alone, or both. Because most disc bulges/ruptures occur posterolaterally, compressing the spinal nerve in the intervertebral foramen, the result is unilateral sensory or motor symptoms that occur in the lower extremity on that side. Occasionally, a disc bulge or rupture may occur in the midline posteriorly. In such an instance, depending on which neurons of the cord are compressed, symptoms may be felt in the lower extremity unilaterally or bilaterally (Fig. 15).

Figure 15. Disc herniation. (A) A posterolateral disc herniation presses on the spinal nerve as it passes through the intervertebral foramen. (B) A midline posterior herniation compresses the spinal cord in the spinal canal. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach. 2015.

Symptoms may also be local if the small nerves in the disc area are compressed. When this occurs, pain occurs directly from this compression. Low back muscles may then protectively splint to stop movement that may further harm the disc. Unfortunately, the severity of the muscle spasming itself may cause pain, and the muscle splinting can increase the compression force on the discs, further aggravating the condition by increasing the size of the bulge or rupture. Note that when a disc condition is acute, inflammation can contribute to the neural compression, with the swelling itself producing symptoms. As the episode passes from the acute stage to the subacute and chronic stages, symptoms often decrease because swelling has diminished.

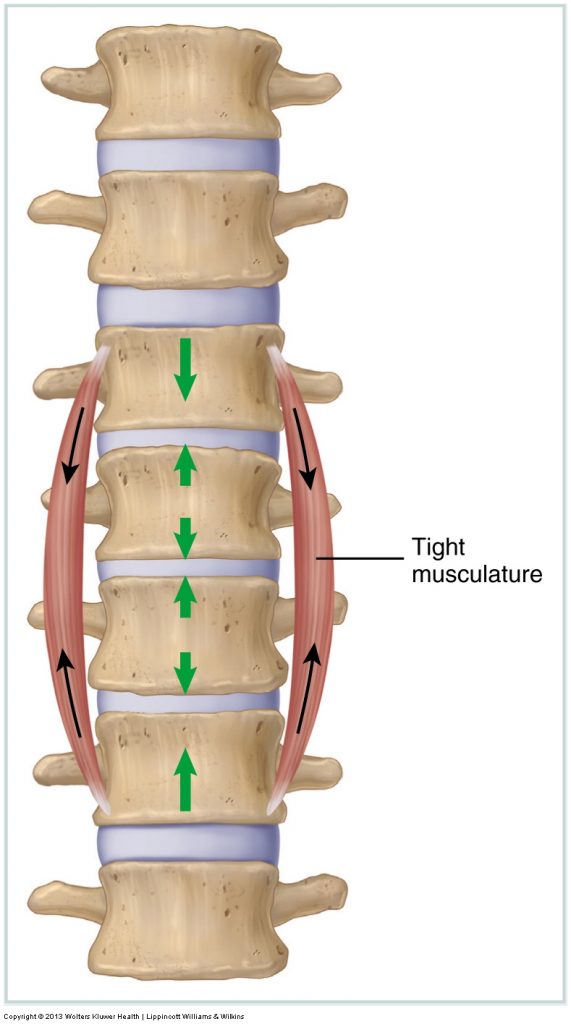

Note: Tight Muscles and Disc Problems

Perhaps the least appreciated but common microtrauma that contributes to spinal disc problems is tight muscles. When spinal muscles become tight, their attachments pull toward the center, drawing the vertebrae crossed by these muscles toward each other. This results in an increased compression on the discs (see accompanying figure). Clients commonly have chronically tight low back muscles, which can contribute significantly to an eventual pathologic disc.

(Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach. 2015.)

Note: Central Canal Stenosis

Another space-occupying condition that can cause referral into the lower extremity is central canal stenosis. As its name implies, the space within the central spinal canal where the spinal cord is located becomes stenotic (narrowed/closed). This condition usually occurs in the elderly as ligaments hypertrophy (thicken) and bone spurs from DJD develop, pushing into the central spinal canal and compressing the spinal cord. This condition usually continues to progress and can become very debilitating. Extension of the lumbar spine usually increases lower extremity pain/symptoms because extension narrows the diameter of the spinal canal; flexion usually relieves lower extremity pain/referral because flexion increases the diameter of the lumbar spinal canal.

Note: Sciatica

Sciatica is caused by compression of the sciatic nerve, or by compression of the nerve roots that contribute to form the sciatic nerve (L4, L5, S1, S2, S3). As explained here, a pathologic disc can cause sciatica. But any compression in the intervertebral foramen or central canal, such as bone spurs from osteoarthritis, ligament hypertrophy, or swelling, can cause sciatica. Sciatica can also be caused by compression of the sciatic nerve due to a tight piriformis; when this occurs, it is often termed piriformis syndrome. Sciatica can even be caused by a direct trauma to the sciatic nerve in the buttock, thigh, or leg.

Note: Meralgia Paresthetica

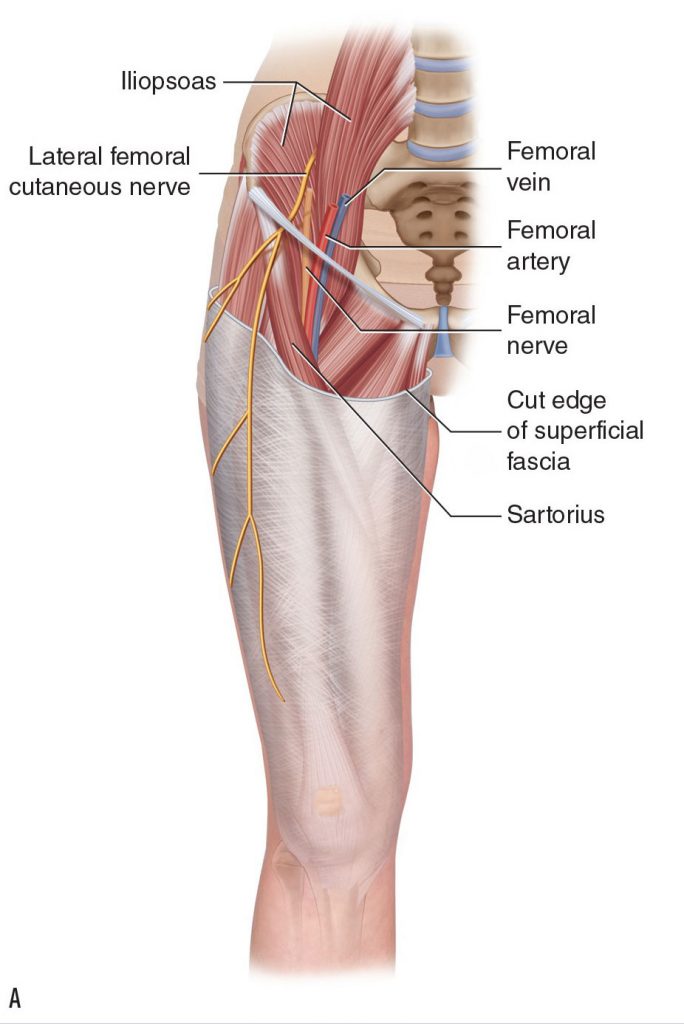

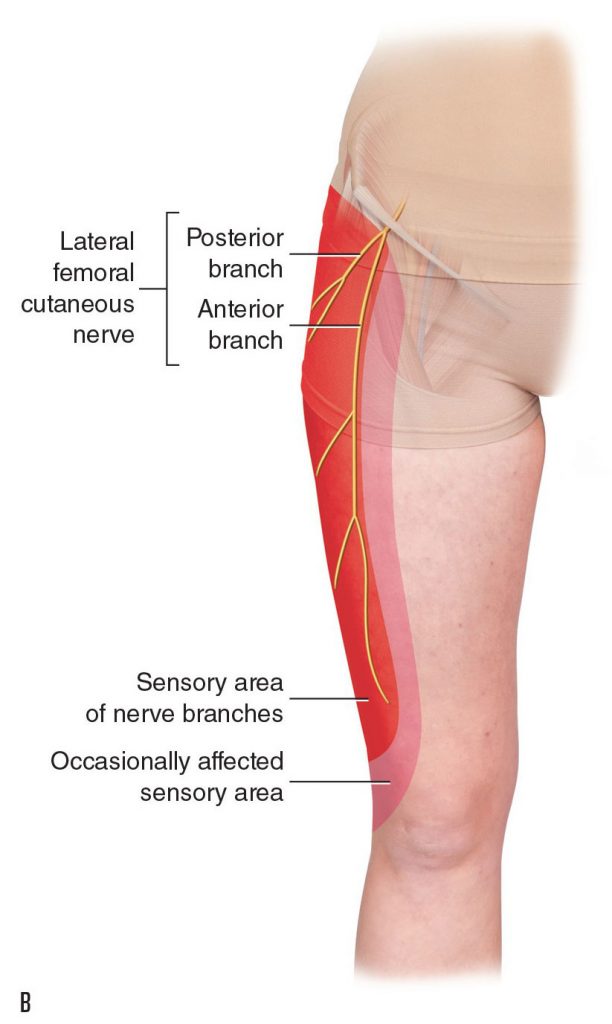

The sciatic nerve is not the only nerve that can be compressed and cause referral into the lower extremity. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, which exits from the pelvis into the anterolateral thigh between the pelvic bone and the inguinal ligament, can also be compressed. When this occurs, the resulting condition is called meralgia paresthetica.

Because the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is solely sensory, this condition results only in altered sensation, usually tingling or pain, into the anterolateral thigh (see accompanying figures). The most common causes of meralgia paresthetica are wearing low-rise jeans or a belt too tightly, being overweight with increased weight carried in the anterior abdominal region, and tightness of various hip flexor muscles, including the iliopsoas, sartorius, and/or tensor fasciae latae. With the increased rates of obesity in the United States, the incidence of meralgia paresthetica will likely increase in the future.

Meralgia paresthetica (A) Meralgia paresthetica is caused by compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. (B) Area of sensory symptoms in the anterolateral thigh.

Meralgia paresthetica (A) Meralgia paresthetica is caused by compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. (B) Area of sensory symptoms in the anterolateral thigh.

Although local low back pain or spasming may occur, lumbar pathologic discs often show no local symptoms at all and present with only lower extremity referral symptoms. Pain, tingling, numbness, or weaknesses that are referred in the lower extremity should be a red flag that a disc problem may exist. However, this does not mean that all lower extremity referral symptoms come from a lumbar disc bulge or rupture. Other conditions such as piriformis syndrome (see next section) or meralgia paresthetica may also refer symptoms to the lower extremity. Although a reasonably accurate assessment can be made with the appropriate orthopedic assessment procedures, if a lumbar disc condition is suspected, the client should be referred immediately to a physician for a definitive diagnosis.

Note: Treatment Considerations in Brief for Pathologic Disc

Massage can be extremely beneficial to help decrease muscular spasms associated with a pathologic disc. Stretching is also helpful, but caution is advised if the client’s trunk is extended or laterally flexed to the side of a pathologic disc. It is contraindicated to place the client in any position that causes or increases referral of symptoms into the lower extremity. Icing may help decrease some of the inflammation that accompanies a pathologic disc. Traction is beneficial because it decompresses the disc.

This blog post article is the sixth in a series of twelve articles on musculoskeletal conditions of the low back (lumbar spine) and pelvis.

The articles in this series are:

- Hypertonic / tight muscles

- Myofascial trigger points

- Joint dysfunction

- Sprains and strains

- Sacroiliac joint injury

- Pathologic disc conditions and sciatica

- Piriformis syndrome

- Degenerative joint disease (DJD)

- Scoliosis

- Lower crossed syndrome

- Facet syndrome

- Spondylolisthesis