Manual Therapy Case Study for Upper Crossed Syndrome

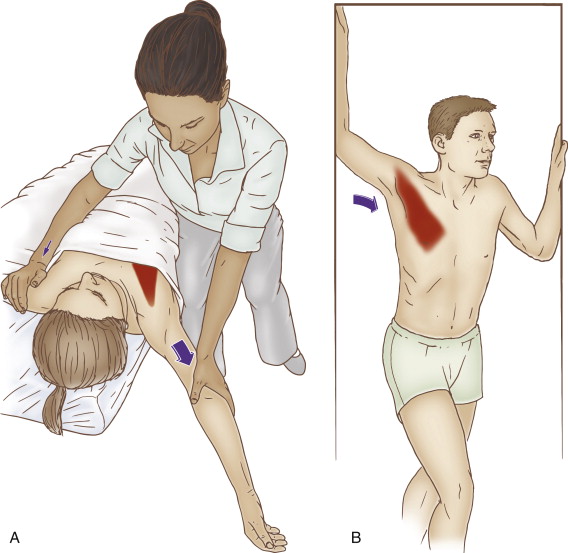

Therapist-Assisted and Self-Care for the Pectoralis Minor. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. The Muscle and Bone Palpation Manual – with Trigger Points, Referral Patterns, and Stretching, 2ed (Elsevier, 2016).

Robert is a 44-year-old office manager at a financial firm. He has decided to go to a clinical orthopedic manual therapist because he has noticed that his posture is increasingly rounding forward. He does not have any appreciable pain, although he has noticed increased tightness and discomfort in his upper back and neck. His main concern is that his posture will become so bad that he will not look professional and it will affect his stature at his job.

The therapist performed a static assessment of his posture and noted the typical upper crossed syndrome with a hyperkyphotic thoracic spine, a hypolordotic lower cervical spine, a hyperlordotic upper cervical spine, protracted head, protracted scapulae, and medially (internally) rotated arms. There was no appreciable presence of lower crossed syndrome or rounded low back. Palpation assessment revealed tight pectoralis and cervical extensor musculature, as well as tightness of the subscapularis and the teres major. And muscle testing showed weakness of the glenohumeral lateral rotators, scapular retractors, and upper thoracic paraspinal extensors. The therapist also performed assessment tests for thoracic outlet syndrome and space-occupying lesions in the neck; these conditions tested negative.

Thai massage technique for stretching the shoulder girdle and pectoralis muscles into retraction and the thoracic spine into extension. Permission: Joseph E. Muscolino.

Given the assessment of upper crossed syndrome, the therapist recommended two one-hour massages per week for four weeks and one one-hour massage per week for the following 8 weeks. The therapist also referred the client/patient out to a Pilates instructor with the request that the Pilates instructor pay specific focus on correcting the dysfunctional upper crossed postural distortion pattern.

Therapist-Assisted and Self-Care Stretching of the Pectoralis Minor. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. The Muscle and Bone Palpation Manual – with Trigger Points, Referral Patterns, and Stretching, 2ed (Elsevier, 2016).With the client/patient supine, heat was placed on the pectoralis region as gentle to medium pressure soft tissue manipulation was done to the posterior neck for approximately 5-10 minutes. Soft tissue work was then done to the pectoral region for 5-10 minutes. The pectoral region was then stretched with regular stretching as well as pin and stretch technique. Soft tissue manipulation was then applied to the subscapularis. The client/patient was then turned to the prone position. Heat was placed on the teres major and upper latissimus dorsi while light to medium pressure work was done to the posterior cervicothoracic musculature for approximately ten minutes. Heat was then placed on the posterior cervicothoracic region while the teres major and latissimus dorsi were worked for approximately five minutes. The client/patient’s arm was then stretched into lateral rotation. With the client/patient supine, the glenohumeral joint was mobilized. The session was completed with a stretch to the upper thoracic region as the client/patient was seated. Each session was carried out in a similar manner, with increasing depth of pressure and assertiveness of stretching as Robert gradually improved. Robert was also given self-care stretches for the pectoralis, glenohumeral joint medial rotation, and cervical-cranial-thoracic musculature, and told to perform these stretches two to three times per day after hot shower. Proper posture at work and home was then discussed.

At the end of twelve weeks, Robert’s posture showed the beginning of clear improvement. Frequency of clinical orthopedic massage was dropped to once every two weeks while Pilates was continued at twice per week for another twelve weeks. At the end of this time frame, Robert’s posture had improved markedly. For proactive self-care, Robert continues to receive clinical orthopedic massage once or twice each month and continues to do Pilates once per week with an instructor and twice per week at home on his own.