Introduction to The Unusual Suspects

There are many hundreds of muscles in the human body, yet it is interesting to see how often the same few muscles are discussed, written about, and assessed as the causes of our clients’ problems. I like to describe these muscles as the usual suspects. When a client has pain in the gluteal region, we look for it to be the piriformis. If the pain is in the anterior hip, the psoas major is first on our radar. If there is pain in the back of the neck, it must be the upper trapezius. But what about all the other muscles in the body? I am not trying to say that the usual suspect muscles are not important. They are. Because of their unique role in movement and stabilization patterns, they probably are more important on average than any one of their neighbors; that is why they have earned the status of being the usual suspects. I am just trying to say that a usual suspect is not always the guilty party. Sometimes it is an unusual suspect, a less well-known muscle, that is the underlying cause of our client’s pain and dysfunction pattern.

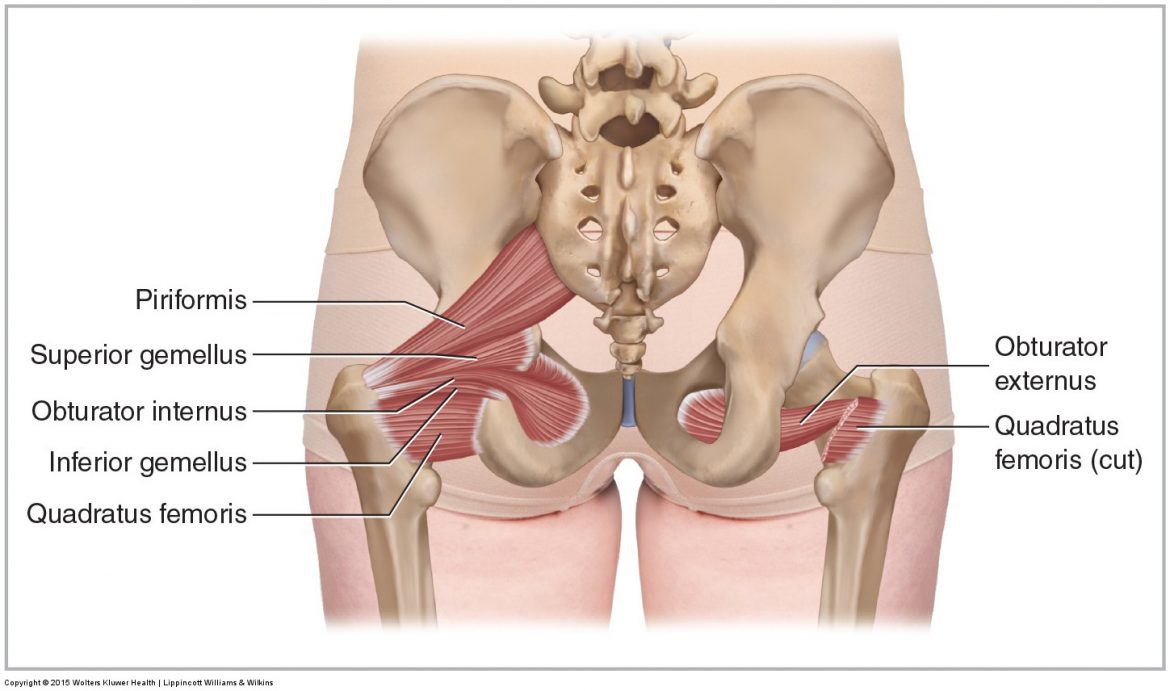

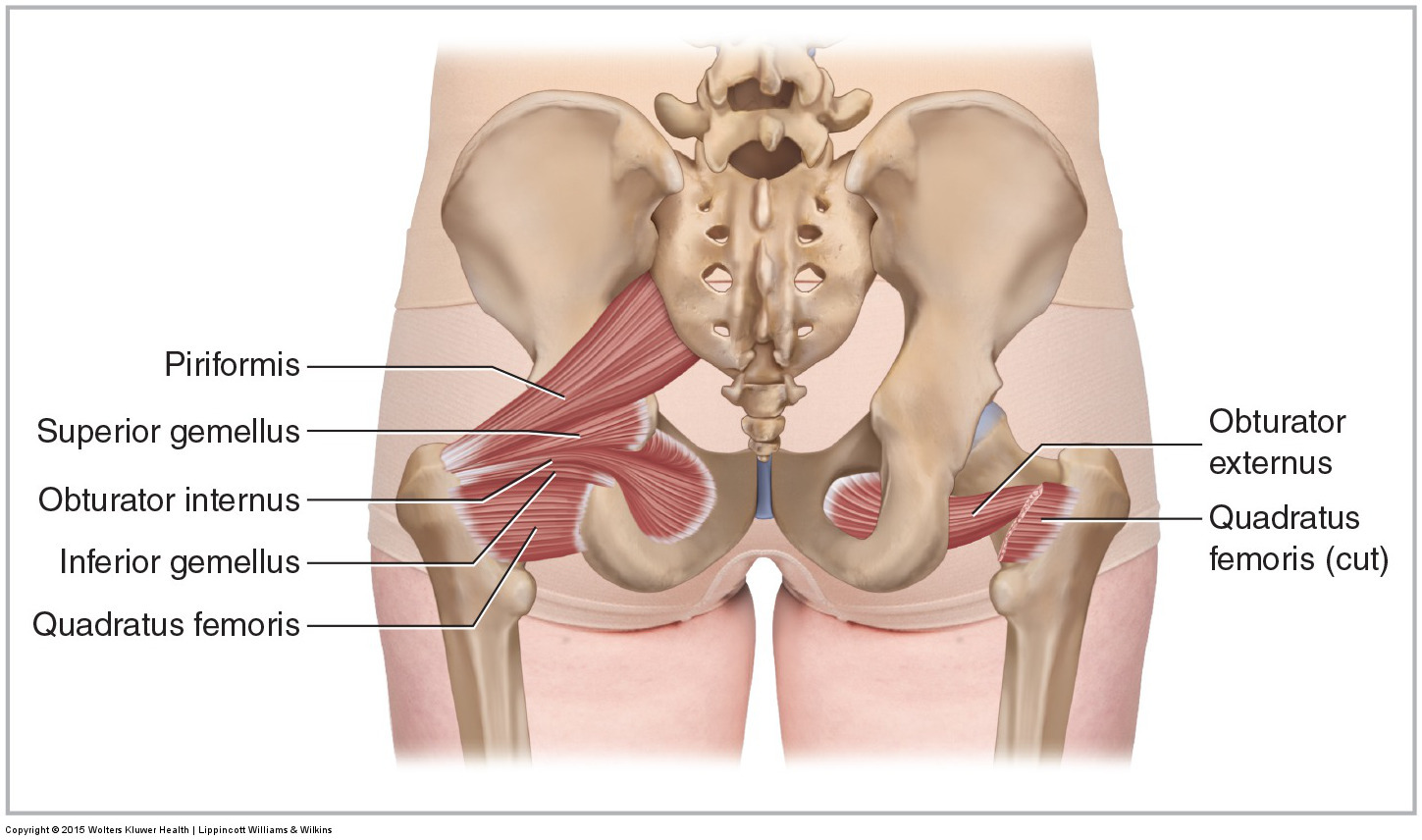

The quadratus femoris of the deep lateral rotator group is an “unusual suspect,” especially compared to its much more well-known neighbor, the piriformis.

Note: This blog post article is the first in a series of 8 posts on

Unusual Suspect Muscles of the Body*

The 8 Blog Posts in this Series are:

- Introduction

- Palmar Interossei (PI)

- Flexor Pollicis Longus (FPL)

- Quadratus Femoris (QF)

- Coccygeus & Levator Ani

- Sternohyoid

- Longus Colli & Longus Capitis

- Other Unusual Suspects…

* This series of blog post articles is modified from an article originally published in massage and bodywork (m&b) magazine: The Unusual Suspects. November/December 2016 issue.

In this series of blog posts are examples of some of these less well-known, unusual suspect muscles that I believe are worthy of our attention. For each muscle, we will review its attachments and actions, how to palpate and stretch it, and then discuss a brief case study of a client for whom this muscle was the key to unlocking their condition and restoring their health. An unusual suspect muscle may not often prove to be the cause of our client’s condition; but when it is, our awareness and knowledge of the muscle, along with our willingness to look for and assess it, can make all the difference, not only in our client’s health, but also in the success of our practice.

Note: Chronicity, not Severity

Case studies are presented to demonstrate how appropriate assessment and treatment can be successful toward resolving a client’s problem. For this reason, case studies are often success stories in which one or a few treatments help to resolve the client’s condition. But as any long-practicing therapist knows, most of our clients’ conditions are not miraculously cured with a session or two. Many of the case studies presented here were as successful as they were because the client chose to seek care very soon after the condition began. An important principle of manual and movement therapy is that our biggest enemy is not the severity of the condition, but rather the chronicity; in other words, how long the condition has been present. The longer the client waits before seeking care, the more the condition becomes entrenched, with patterns of nervous system engagement becoming more facilitated and fibrous adhesions building up.

Note: “Characteristic Pain Pattern”

When examining the client, it is not enough to just find pain and dysfunction. It is important to find the specific pain and dysfunction that has brought the client to our office. Otherwise, we may be treating other conditions, that although possibly important as well, will not resolve their reason for seeking care in the first place. This can frustrate them and make them feel that we are not paying appropriate attention to them, which in this case we are not. So what we need to do during the physical exam is find what reproduces their “characteristic pain pattern.” Once found, we will then have the correct target for our treatment and can resolve the condition that the client is experiencing.

We Need to Look in the Correct Place…

There is a corny but apt joke about a mother who comes home to find her 12 year-old son on his hands and knees in the dining room, seemingly searching for something. When she asks him if he lost something, he answers yes, he lost a quarter. She asks him if he lost it in the dining room, and he answers no; he lost it in the living room. So, a bit perplexed, she asks him why then is he looking in the dining room. He responds: “The light’s better in here.”

This may seem like a silly story, and indeed, on one level it is. But on another level, there is a lesson to be learned here. If we are not looking in the right place, we will never find what we are looking for. We shouldn’t look just where it is easy to look, where the light is better, so to speak; rather we need to look even in the more obscure, less well-lit places. If we only check the usual suspect muscles, we will never discover how involved and important some of the other, less well-known, unusual suspect muscles are.