The Sternocleidomastoid (SCM)

Listen to the word as you say it: “sternocleidomastoid.” Even its name is special, the six syllables rhyming with themselves in a three-beat cadence that rolls off the tongue like no other anatomical name.

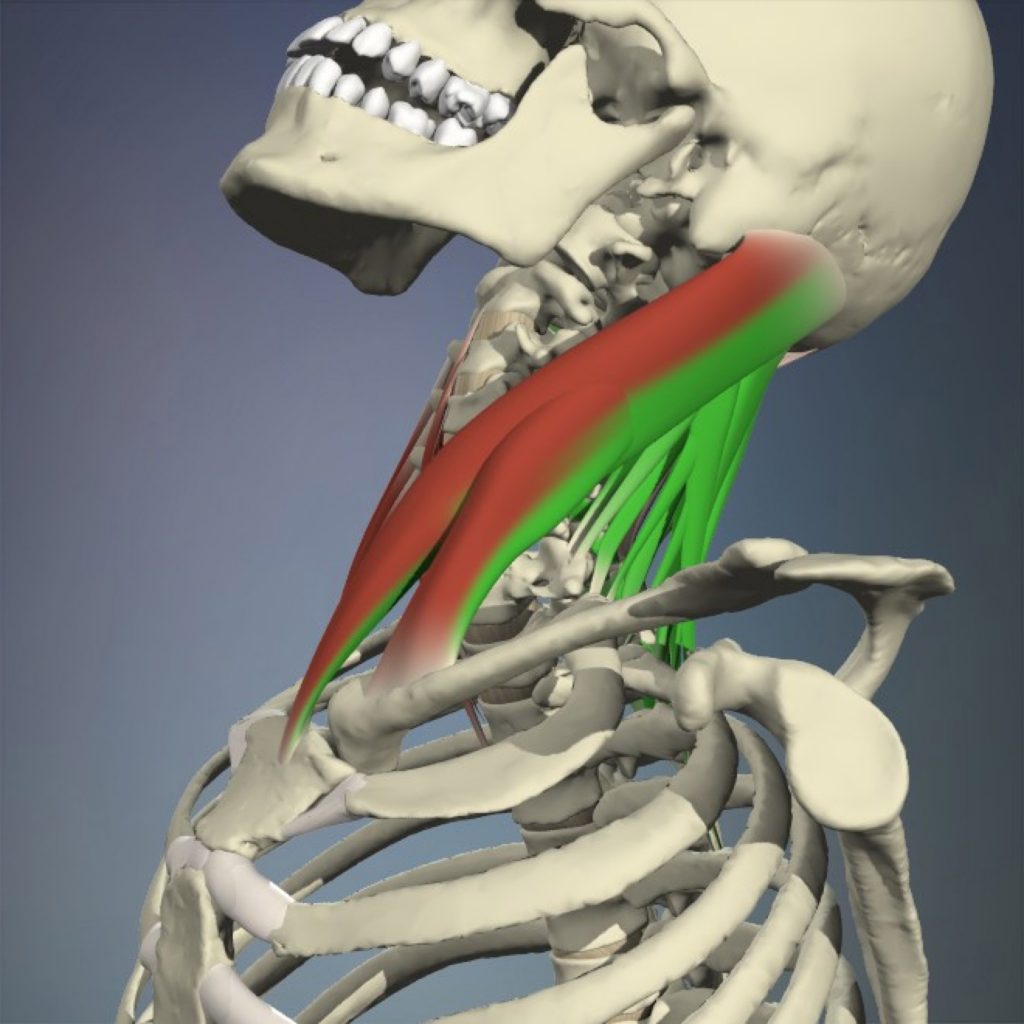

Image 1: The sternocleidomastoids (SCMs) are frequently injured by being eccentrically overstretched (red) in hyperextension whiplash injuries. Image courtesy Primal Pictures, used by permission.

And whether you hear this unique muscle’s name as a rapper’s multisyllabic rhyme, a poet’s lyrical trochee, or simply as a mouthful of Latin jargon, your hands-on work with the sternocleidomastoids (less poetically known as the “SCMs”) can be a crucial part of addressing many client complaints. These include cervical pain and stiffness, the effects of whiplash (Image 1) jaw issues, and several other primary indications as listed in the sidebar below. In addition to that list, hands-on work with the SCMs has also been said to help with a host of other less-obviously related conditions, such as facial, sinus, and nasal pain; vertigo, dizziness, car sickness; tinnitus and hearing loss; upper chest soreness; persistent coughs; swallowing difficulties and throat pain; and more. [1]

Not only is the SCM implicated in an extraordinarily large number of client complaints, but it is also involved in many (if not all) head and neck movements. Connecting the cranium to the shoulder girdle and axial skeleton by wrapping diagonally around the neck, the SCMs lift the sternum and clavicles; turn, bend, and flex the cervical spine; as well as extend, rotate, and tilt the head.

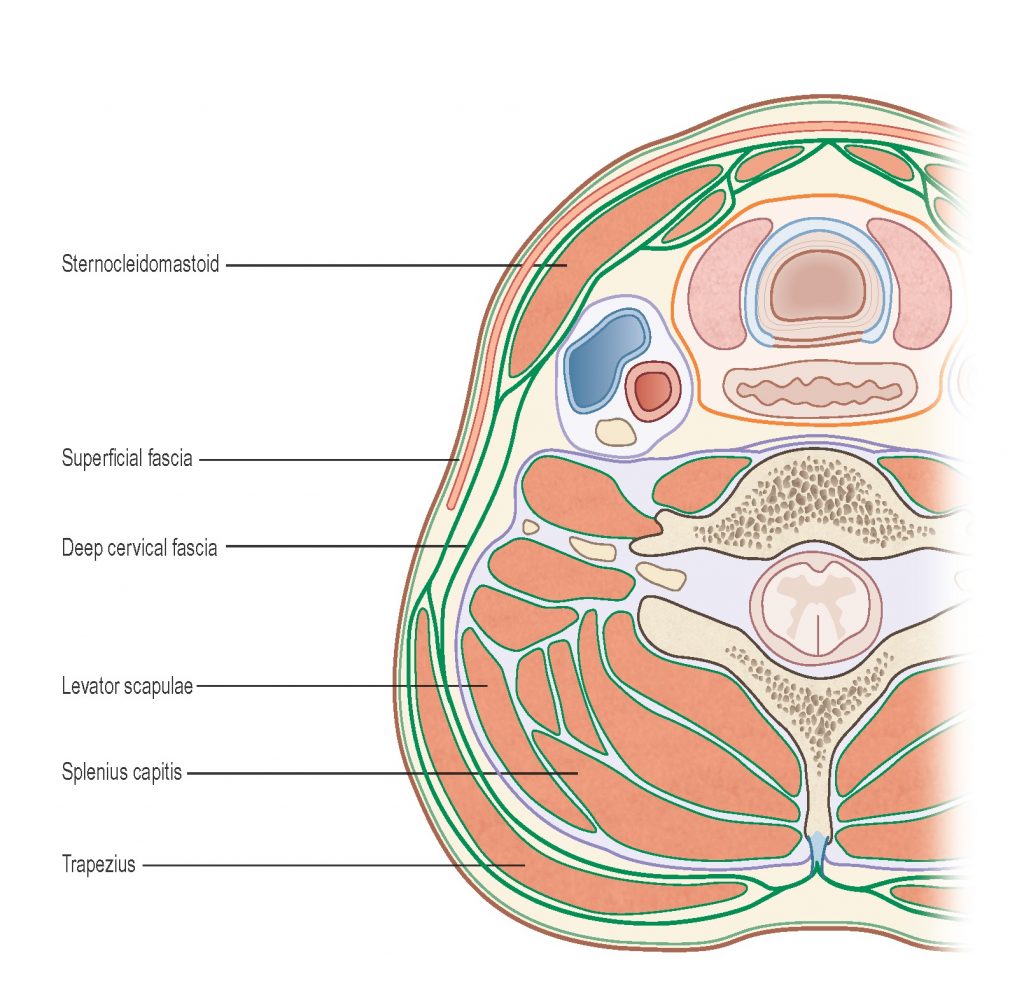

Image 2: Cross section through the cervical spine. Courtesy Til Luchau.

And no other neck muscles seem quite so sensitive as the SCMs, probably due to the many nerves associated with them and their enveloping connective tissues, the outer (or investing) layers of the deep cervical fascia (Image 2). This multilayered fibrous membrane also encloses the trapezius, as well as the muscles of mastication (masseter, pterygoids, temporalis), and is perforated by, enfolds, and interfaces with numerous sensory and motor nerves (Image 3).

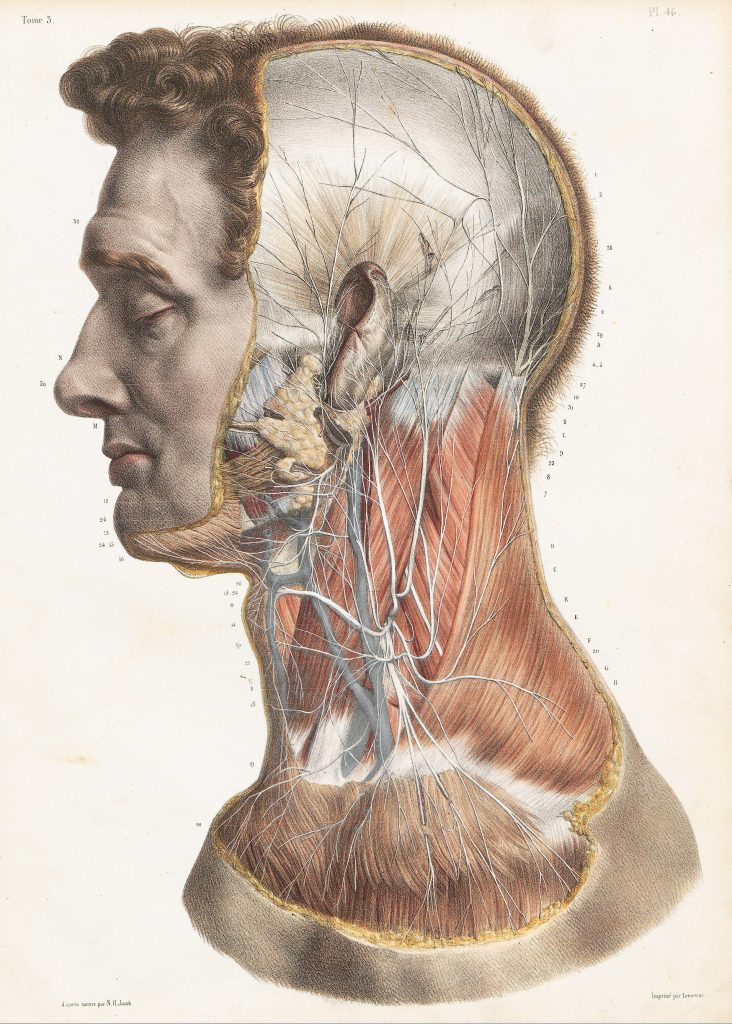

Image 3: The SCM is surrounded and perforated by numerous sensory and motor nerves, lymph vessels, and vasculature (the external jugular vein visible on the SCMs surface, making it crucial that your work here be sensitive and gentle. Image from Bourgery, JBM. Traité complet de l’anatomie de l’homme: comprenant la médicine opératoire. 1830-1849.

For example, the deep cervical fascia of the SCMs’ inner interface forms part of the carotid sheath, which surrounds the vagus nerve, the main parasympathetic trunk. The SCM’s inner fascia also gives rise to the prevertebral fascia, which extends across the anterior surfaces of the cervical vertebrae.[2] Injury to the prevertebral fascia and its associated sympathetic ganglia is thought to be a physical cause of the dizziness, anxiety, and other sympathetic autonomic disturbances sometimes seen after hyperextension whiplash injuries. [3]

And although pain (especially chronic pain) can have many aspects in addition to any tissue-based contributors, the SCM’s fascial layers seem to be involved in many cases of chronic neck pain (CNP). In a recent randomized clinical trial comparing the cervical fascia in people with and without CNP, the fascia of the SCM (and medial scalene) was on average significantly thicker and stiffer in those with pain. Fascia-oriented manual therapy was seen to improve both these measures; tissue thickness, stiffness, and reported pain all decreased as a result of hands-on fascial work. [4]

Digital COMT

Did you know that Digital COMT (Digital Clinical Orthopedic Manual Therapy), Dr. Joe Muscolino’s continuing education video streaming subscription service for massage therapists (and all manual therapists) and movement professionals, has six folders with video lessons on Manual Therapy Treatment, including an entire folder on Stretching, as well as a folder on Pathomechanics, another on Anatomy, and many more? Digital COMT adds seven new video lessons each and every week. And nothing ever goes away! Click here for more information.

SCM Differentiation Technique

In the Advanced Myofascial Techniques series as taught by the Advanced-Trainings.com faculty, we use the SCM Differentiation Technique in our “cold” whiplash protocol, which is most appropriate only after any initial autonomic reactivity and muscle spasm have diminished (usually several weeks or more after the initial injury, though sometimes longer). It can be used cautiously and very gently with mild “hot” whiplash, but only when there is an absence of muscular spasm so as to avoid aggravating the already irritated condition. This technique is also useful any time we want to increase the client’s ability to move the neck and head without undue contraction or dominance by the SCM, since the technique’s purpose is to gently differentiate the outer layers of the neck, and simultaneously teach new, easier movement possibilities.

Start with your client side lying, without a pillow if that’s comfortable, as this allows you to work the upper SCM in a slightly lengthened (eccentric) state (Images 4 and 5). Because it does not involve sliding on the skin, too much oil or lubricant will make this technique difficult to perform. When performing this technique, pay special attention to gentleness, patience, and increasing client awareness, rather just on tissue effects alone. Finish by repeating the technique in a seated position to help the client apply their new awareness to an upright posture. Performed correctly, this technique will leave your clients enjoying lighter, easier and more comfortable movement.

Images 4 and 5: The SCM Differentiation Technique involves delicate, comfortable, but specific finger placement around the medial border of the SCM, feeling for fascial elasticity and differentiation between the muscle and its underlying structures. Use active client eye movements, followed by slow, active neck rotation, all the while monitoring the client’s ability to leave the SCM largely relaxed. Images courtesy Advanced-Trainings.com

SIDEBAR

Key Points: SCM Differentiation Technique

Indications

- Neck pain or stiffness

- “Cold” whiplash (3–6 weeks or more since injury; no muscular spasms)

- Positional or postural issues, such as head-forward position or torticollis

- Headaches: both tension-type, and migraines

- Jaw pain, tension, and TMJD

Purpose

- Increase elasticity and layer differentiation of the deep cervical fascia, especially under (medial to) the SCM

- Reduce and reeducate SCM tonus by refining proprioceptive coordination of SCM engagement in movement initiation.

Instructions

- After other preparatory work, use gentle, specific, and static (not sliding) pressure medial and deep to the SCM.

- Cue active client movements, as described below.

- Monitor client’s comfort and ability to fully relax, and modulate pressure and pace accordingly.

Movements

- While maintaining SCM relaxation, slowly look left and right with just the eyes

- Once ability to move the eyes with relatively relaxed SCM is established, add slow, gentle neck rotation, looking for ways to move head without over-contracting the SCM.

- Possible cues: “Let the back of your head turn as much as the front.” “Leave your head heavy.” “Use your eyes instead of your muscles to start the movement,” etc.

- Repeat with client sitting or standing.

Homework

- Practice head rotation with relaxed SCM when side-lying, seated, and standing, with special attention to initiation of movement with out over-contraction of SCM.

For More Learning

- “Neck, Jaw & Head” and “Whiplash” in the Advanced Myofascial Techniques series of workshops and video courses.

- Advanced Myofascial Techniques, Volume 2 Chapters 8-10. (Handspring 2016)

Bio: Til Luchau is a Certified Advanced Rolfer, the author of Advanced Myofascial Techniques (Handspring Publishing, 2016) and a member of the Advanced-Trainings.com faculty, which offers distance learning and in-person seminars throughout North America and abroad. Contact him via [email protected] and Advanced-Trainings.com’s Facebook page.

Video…Watch Til Luchau’s technique videos and read his past articles in Massage & Bodywork’s digital edition, available at www.massageandbodyworkdigital.com, www.abmp.com, and on Advanced-Trainings.com’s Facebook page.

Sources:

- Shifflett, CM. (2011) Migraine Brains and Bodies. North Atlantic.

- Lee, K.J. (2012). Essential Otolaryngology (10 ed.). McGraw Hill. 559–60.

- Gifford, L. ed. (2013). Topical Issues in Pain 3: sympathetic nervous system and pain, pain management, clinical effectiveness. Physiotherapy Pain Association. 34.

- Stecco A. et al (2014). Ultrasonography in myofascial neck pain: randomized clinical trial for diagnosis and follow-up. Surg Radiol Anat 2014 Apr; 36(3):243-53

(Note: This article was originally published in massage and bodywork magazine.)

(Click here for a blog post article on Motion Palpation [Joint Play] Assessment of the Neck.)