Introduction:

There is a hypothesis that fascia may play an important role in chronic low back pain. Following on a series of experiments, researchers have shown that fascial injury with resultant movement restriction caused loss of fascial mobility contralaterally (i.e., on the opposite side of the body from the injury). Now in a new study, researchers tried to determine if stretching to restore movement could reverse this fascial restriction.

Background Studies:

In 2011, Dr. Helene Langevin and colleagues from University of Vermont published a study (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21929806) that demonstrated that people with chronic low back pain (LBP) have increased thickness and decreased mobility of the thoracolumbar fascia. The authors hypothesized that these structural and functional abnormalities of fascia in subjects with LBP could represent a fibrotic process resulting from an initial soft tissue injury involving fascia, followed by movement restriction that could be worsened by pain or fear of pain. They added that a loss of shear plane mobility between adjacent layers within the thoracolumbar fascia could be one of several interrelated factors in the development of low back pain since the lack of mobility may alter the biomechanics of the trunk as well as the sensory input (nociceptive and/or non-nociceptive) originating from the fascia.

Following on, in 2016 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26820883), researchers used a porcine model to test whether decreased fascial mobility can be experimentally reproduced in a porcine (pig) model that suffered a local fascial injury with movement restriction. The study induced a unilateral thoracolumbar fascial injury on the pigs and also created a movement restriction using a “hobble” device linking one foot to a chest harness for eight weeks. The researchers then used an ultrasound instrument to measure the thoracolumbar fascial thickness and fascial shear plane mobility (shear strain) during passive hip flexion on both the injured side (ipsilaterally) and the non-injured side (contralaterally). They found that the combination of injury plus movement restriction had additive effects on reducing fascial mobility on the non-injury (contralateral) side with a 52% reduction in shear strain of the fascia compared with controls. There was a 28% reduction in fascial mobility for those pigs that had movement restriction alone. Thus, both fascial injury and movement restriction correlate with fascial restriction, but the combination of fascial injury and movement restriction showed greater fascial restriction.

Digital COMT

Did you know that Digital COMT (Digital Clinical Orthopedic Manual Therapy), Dr. Joe Muscolino’s continuing education video streaming subscription service for massage therapists (and all manual therapists) and movement professionals, has six folders with video lessons on Manual Therapy Treatment, including an entire folder on Stretching, as well as a folder on Pathomechanics, another on Anatomy, and many more? Digital COMT adds seven new video lessons each and every week. And nothing ever goes away! Click here for more information.

Present Study:

Now, in a new study published in the September 2017 issue of American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, scientists investigated whether this fascial immobility and movement restriction could be reversed by employing daily stretching for one month.

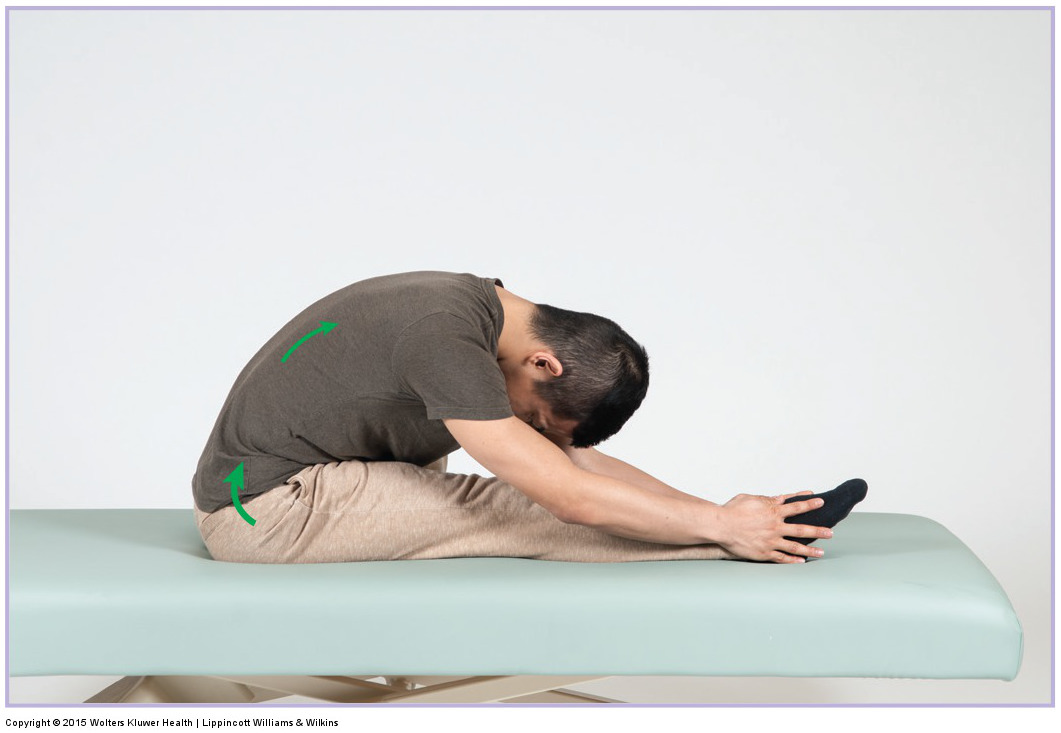

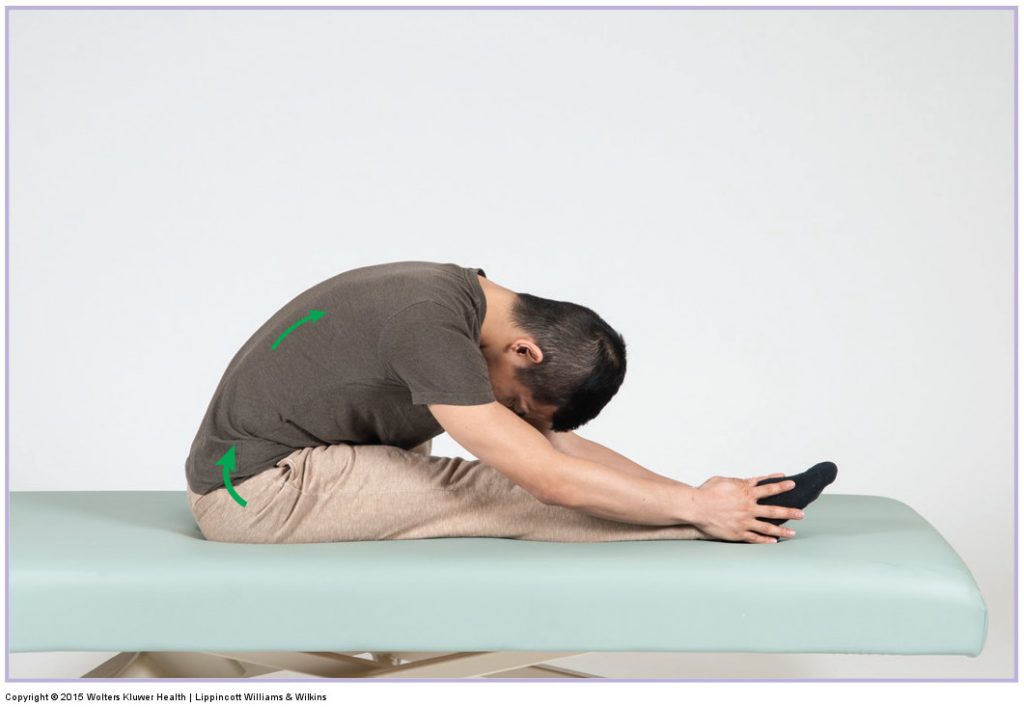

The study used thirty pigs which were randomized to control, injury, or injury + hobble (movement restriction) for eight weeks. The hobble restricted hip extension on the side of injury (ipsilaterally). At week eight, the injury + hobble group was subdivided into continued hobble, removed hobble, and removed hobble + stretching (passively extending the hip joint for 10 minutes daily).

The results showed that removing hobbles restored normal gait speed but did not restore fascial mobility. Further, the group that received daily passive stretching did not show additional fascial mobility benefit when compared to the group that simply had the hobbles removed. Both treatments (removed hobble and stretching) also did not produce significant improvement in fascia mobility.

The authors noted that all ultrasound measurements of fascial mobility were made on the side contralateral to the injury. Thus, observed reductions in fascial mobility were not due to immediate scarring but rather reflected a more diffuse response of fascia to the injury that was exaggerated by the movement restriction. The authors suggested that persistent and extensive involvement of fascia after a minor back injury may cause long-term biomechanical abnormalities in the back.

The authors concluded that reduced fascia mobility in response to injury and/or movement restriction worsens over time and persists even when movement is restored.

Conclusion:

This study does not conclude that stretching is not useful toward reducing fascial restrictions, only that the specific stretching method that was used in this study was not effective. Reversing fascial restriction may require either longer than one month of passive stretching, or may require a different treatment “dose” modality; perhaps a different protocol of stretching or the substitution or addition of another treatment modality entirely.

(Note: This article was reproduced with permission from Terra.Rosa.com.au)

(Click here for another blog post article on the effects of stretching on myofascial tissue.)