Biomechanics of Elongation of the Spine

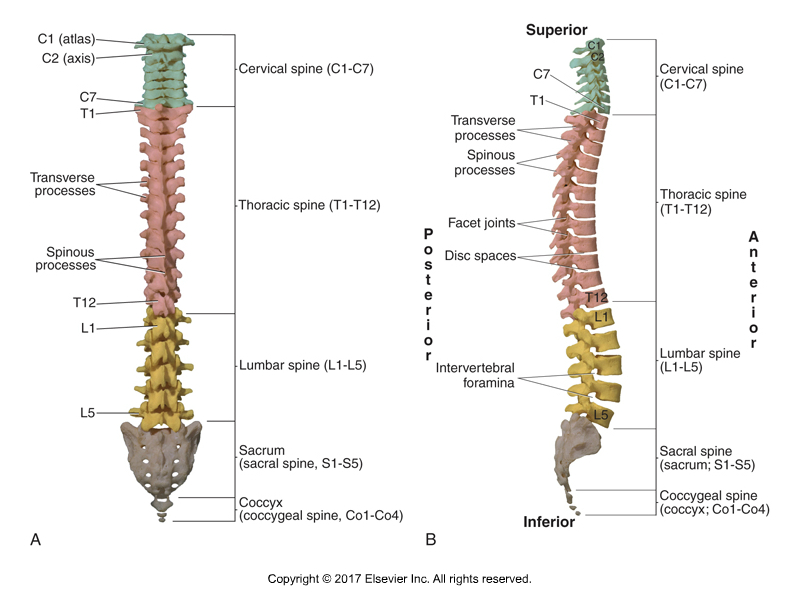

Posterior and Right Lateral Views of the Spine. Permission Dr. Joe Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3rd Edition (Elsevier, 2017).

Elongation of the spine is often spoken of by Pilates instructors as one of the objectives for clients to achieve. But what exactly is elongation of the spine and how is it achieved biomechanically? This blog post article explores this topic.

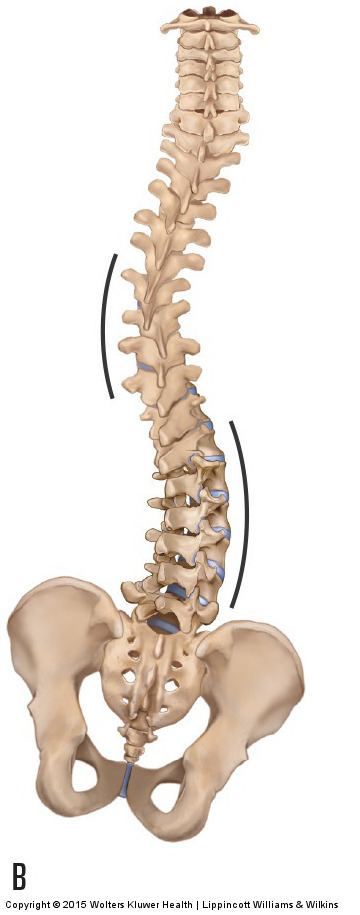

Lessen the Curves of the Spine

Elongation of the spine is actually a simple concept. As its name states, it is making the spine longer. How is this done? By lessening the curves of the spine. Simply put, an increased curve shortens the spine, so it follows that when curves are excessive, to make the spine longer, we need to lessen the degree of the curves. This involves strengthening and stretching myofascial tissue in the “opposite direction” of the curve.

Spinal Curves

A healthy adult spine has curves in the sagittal plane. The sacral spine and thoracic spine have curves of flexion, termed kyphotic curves or kyphoses (kyphosis, singular). And the lumbar spine and cervical spine have curves of extension, termed lordotic curves or lordoses (lordosis, singular). It is normal and healthy to have these kyphotic and lordotic curves.

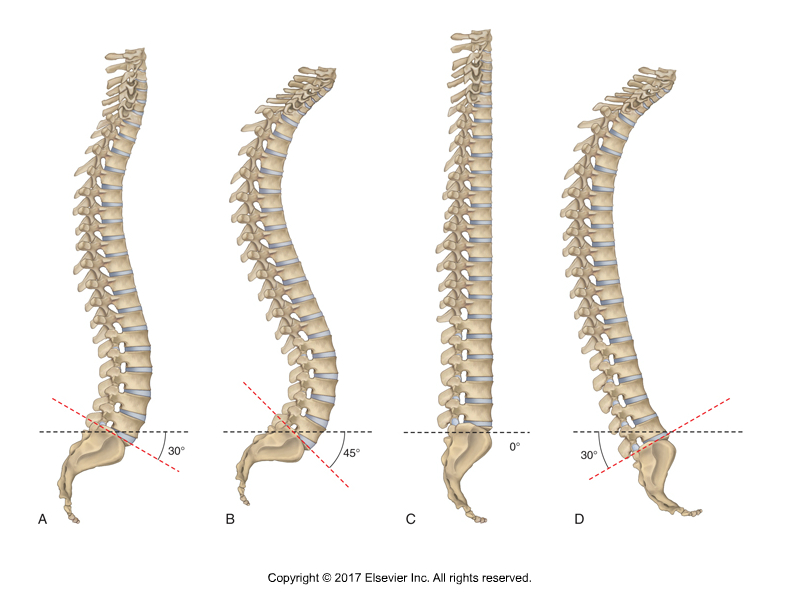

Common Postures of Pelvic Tilts and Spinal Curves. A, Healthy pelvic anterior tilt and healthy lumbar lordotic and thoracic kyphotic curves. B, Excessive pelvic anterior tilt with lumbar hyperlordosis and thoracic hyperkyphosis. C, Decreased anterior pelvic tilt and lumbar hypolordosis and thoracic hypokyphosis. D, Posterior tilt of the pelvis with hypolordotic (kyphotic) lumbar spine and hyperkyphotic thoracic spine. Permission Dr. Joe Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3ed (Elsevier, 2017).

But when these curves become excessive, the client can be described as having a hyperkyphotic and/or hyperlordotic curve. Most often, the client has a hyperlordotic lumbar spine and/or a hyperkyphotic thoracic spine. The sacral spine is fused in an adult, so its curve cannot be changed; the cervical spine can also have an altered curve, but this article on elongation of the spine will focus on the curves of the thoracolumbar region.

Lumbar Lordotic Curve

So, to lengthen and achieve elongation of the spine in the lumbar region, given that the lumbar lordosis is a curve of extension, we need to flex the lumbar spine. To accomplish this, we need to strengthen flexion musculature of the lumbar region and stretch/lengthen the extensor myofascial tissue of the lumbar region. This involves strengthening the musculature of the anterior abdominal wall, specifically the rectus abdominis, external abdominal oblique, and internal abdominal oblique. And it means stretching the paraspinal extensor musculature (and fascial tissue) of the low back (erector spinae and transversospinalis musculature, as well as the quadratus lumborum [QL], and associated ligaments and fascial sheathes). Another way to look at this is that we want to strengthen the musculature on the convex side of the curve (flexors on the anterior side) and stretch/lengthen the myofascial tissue on the concave side (extensors on the posterior side) of the curve.

Thoracic Kyphotic Curve

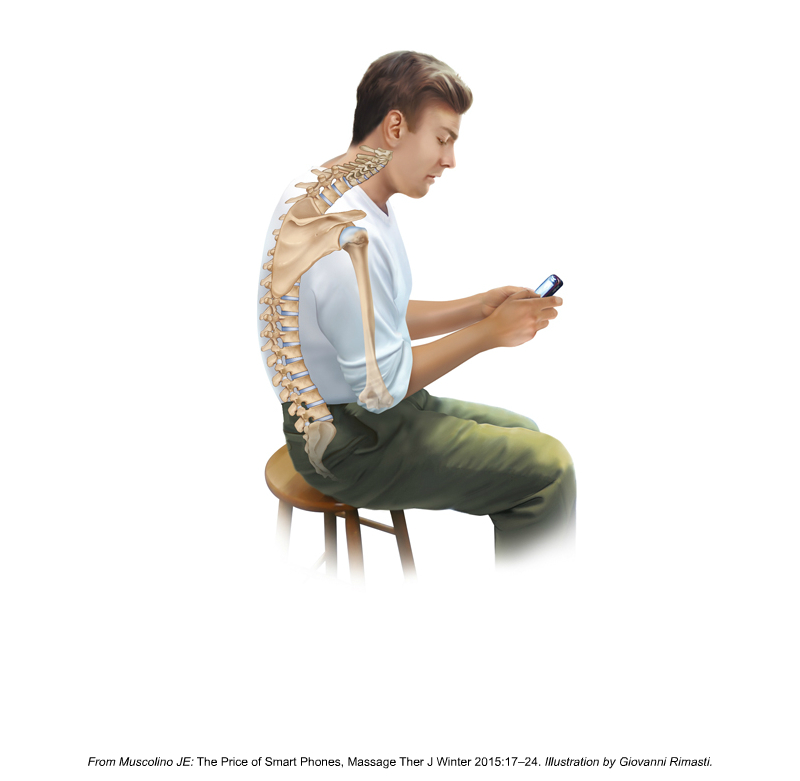

Hyperkyphosis of the Thoracic Spine (and decreased anterior pelvic tilt and hypolordosis of the lumbar spine). Permission Dr. Joe Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3ed. (Elsevier, 2017).

In the thoracic region, given that the thoracic kyphosis is a curve of flexion, to achieve elongation of the spine in the thoracic region, we need to extend the thoracic spine. To accomplish this, we need to strengthen extension musculature of the thoracic region (mid to upper trunk) and stretch/lengthen the flexor myofascial tissue of the mid to upper trunk. This involves strengthening the musculature of the posterior thorax, specifically the paraspinal extensor musculature. And it means stretching the pectoralis musculature (and fascial tissue) of the upper trunk / chest, and associated ligaments and fascial sheathes. Again, another way to look at this is that we want to strengthen the musculature on the convex side (in this case, extensor musculature on the posterior side) of the curve and stretch/lengthen the myofascial tissue on the concave side (flexor musculature on the anterior side) of the curve.

(Note: In conjunction with strengthening the extensor musculature of the thoracic region, to successfully create elongation of the spine, it is important to also strengthen the retractor musculature of the shoulder girdle (rhomboids and trapezius, especially the middle trapezius).

Digital COMT

Did you know that Digital COMT (Digital Clinical Orthopedic Manual Therapy), Dr. Joe Muscolino’s continuing education video streaming subscription service for manual therapists and movement professionals, has at present (January of 2019) more than 1,000 video lessons on manual and movement therapy continuing education, including entire folders on massage therapy, stretching, joint mobilization, fitness, Pilates, and yoga. And we add seven (7) new videos lessons each and every week! And nothing ever goes away. There are also folders on Pathomechanics and Anatomy and Physiology, including an entire folder on Cadaver Anatomy… and many, many more on other manual and movement therapy assessment and treatment techniques? Click here for more information.

Sagittal Plane Pelvic Tilt

Certainly, if the client has excessive lumbar and thoracic curves, and we succeed in lengthening them, we will be successful in our goal to create elongation of the spine. But this is essentially impossible if the underlying cause of the excessive thoracolumbar curvature is coming from an excessively anteriorly tilted pelvis. The “base” of the sacrum (its top surface; the sacrum is essentially an upside-down triangle with the base at the top) is the surface upon which the lumbar spine above, and indeed the entire spine, sits. The sacral base can be likened to a pedestal that a statue sits upon. If the pelvis, and therefore the sacrum, is tilted beyond its normal posture, then it is like the pedestal under the statue being tilted. To prevent the statue from being tilted (like the Leaning Tower of Pisa), the lumbar spine must compensate by changing its curve.

Neutral Pelvis (in the Sagittal Plane)

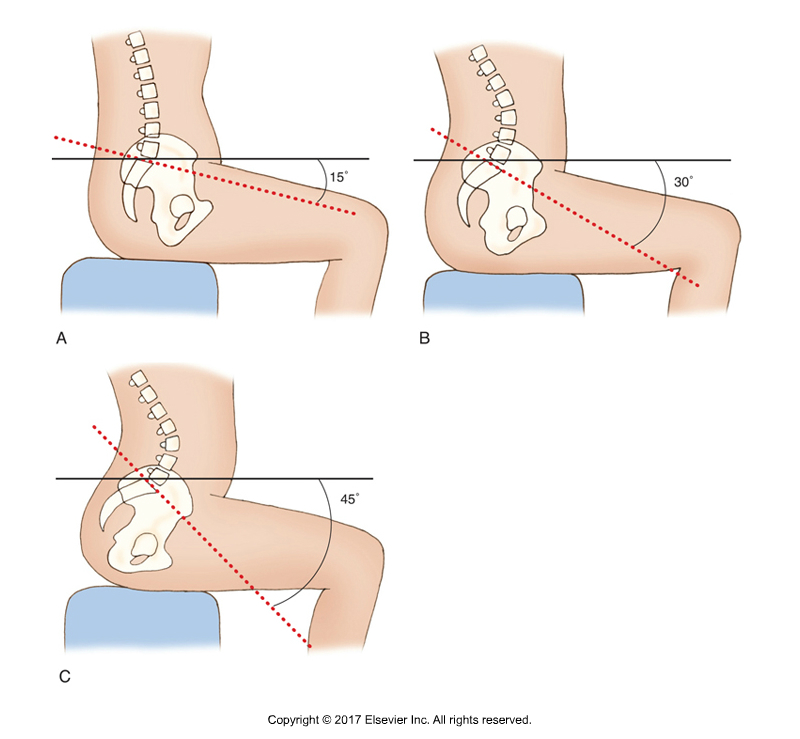

Sacral Base Angles and Spinal Posture. Permission Dr. Joe Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3ed (Elsevier, 2017).

A normal healthy “neutral pelvis” posture involves the sacrum having an anterior tilt of approximately 30 degrees. There is controversary over exactly what defines a healthy neutral posture of the pelvis, but it can be estimated as having what is known as a “sacral base angle” of approximately 30 degrees. (Note: the sacral base angle is defined as the intersection of two lines, one along the sacral base and the other a horizontal line).

When the sacral base angle increases, the pelvis and the trunk would be tilted anteriorly. To prevent this, the lumbar spine must increase its lordotic curve of extension to bring posteriorly the center of mass (body weight) above to be balanced over the pelvis. Then as a consequence, because the upper lumbar spine is now angled back excessively posterior, the thoracic spine must now increase its kyphotic curve of flexion to bring the body weight above back anteriorly to balance over the pelvis and lower trunk below it.

For this reason, if a client has an excessively anteriorly tilted pelvis, the lumbar and thoracic curves essentially must become excessive as a compensation (this postural distortion pattern of the lumbosacral region is known as lower crossed syndrome).

Sagittal Plane Posture of the Pelvis

If our goal is to create elongation of the spine by decreasing the excessive anterior tilt of the pelvis, then we need to strengthen posterior tilters of the pelvis and stretch/elongate/make more flexible the anterior tilters of the pelvis.

Note: Verbiage

Strengthen & Stretch? vs. Tight & Loose vs. Locked Short & Locked Long

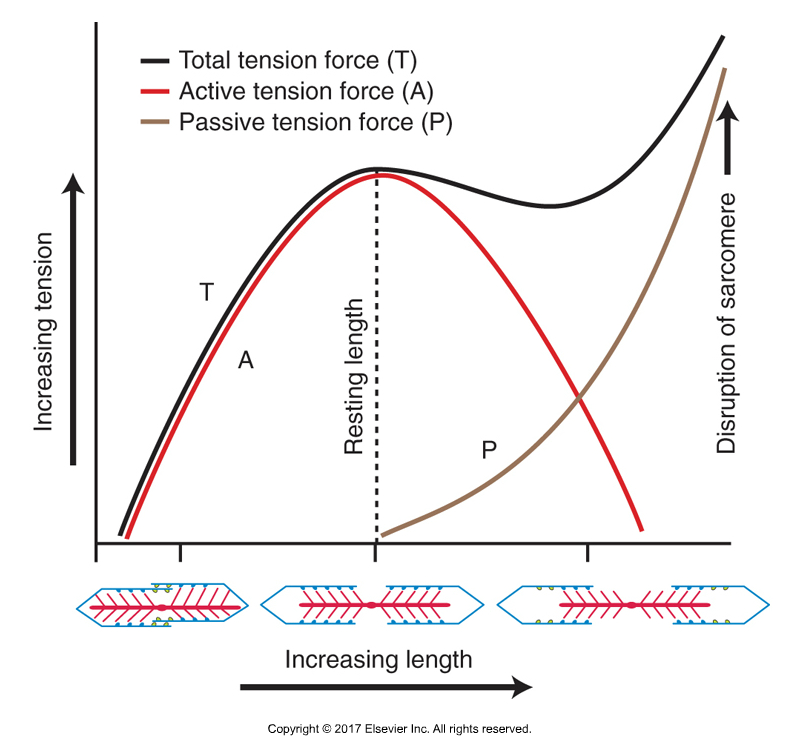

Terminology often changes over time to best describe what we are accomplishing musculoskeletally. Current terminology that best describes the effect we have of strengthening or stretching musculature is to no longer describe that musculature as tight/loose or strong /weak. Instead, the terms “locked long” and “locked short” are more often used now to describe musculature around a joint when there is a postural or functional distortion pattern. If there is a postural distortion pattern, then musculature on both sides of the joint are locked (in other words, tight) and weak. The shortened side is “locked short,” and tight and weak (weak because of the length-tension relationship curve that describes how a muscle becomes weaker when it is shorter or longer than resting length based upon its potential for myosin-actin cross-bridges).

Length Tension Relationship Curve. Permission Dr. Joe Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3ed. (Elsevier, 2017).

And the lengthened side is “locked long” and weak and tight (tight because it is contracting, trying to fight the locked short musculature on the other side of the joint).

Both locked short and locked long musculature are tight and weak. But relatively, the locked short musculature is tighter at baseline tone, so the majority of our focus needs to be on stretching it. And relatively, the locked long musculature is weaker at baseline tone, so the majority of our focus needs to be on strengthening it. So, when there is a postural dysfunctional pattern such a excessive pelvic tilt or excessive spinal curves, we want to strengthen the “locked long” musculature to increase its baseline tone and make it shorter; and to stretch the “locked short” musculature to decrease its baseline tone and make it longer. This then allows the position of the bones and joints to attain a better posture.

Note: The terms “facilitated” and “inhibited” (or “overly facilitated” and “overly inhibited”) are also used. These terms tend to approach the function of the musculature from the perspective of the nervous system. Generally, the locked short musculature is overly facilitated, and the locked long musculature is overly inhibited.

Changing Sagittal Plane Pelvic Posture

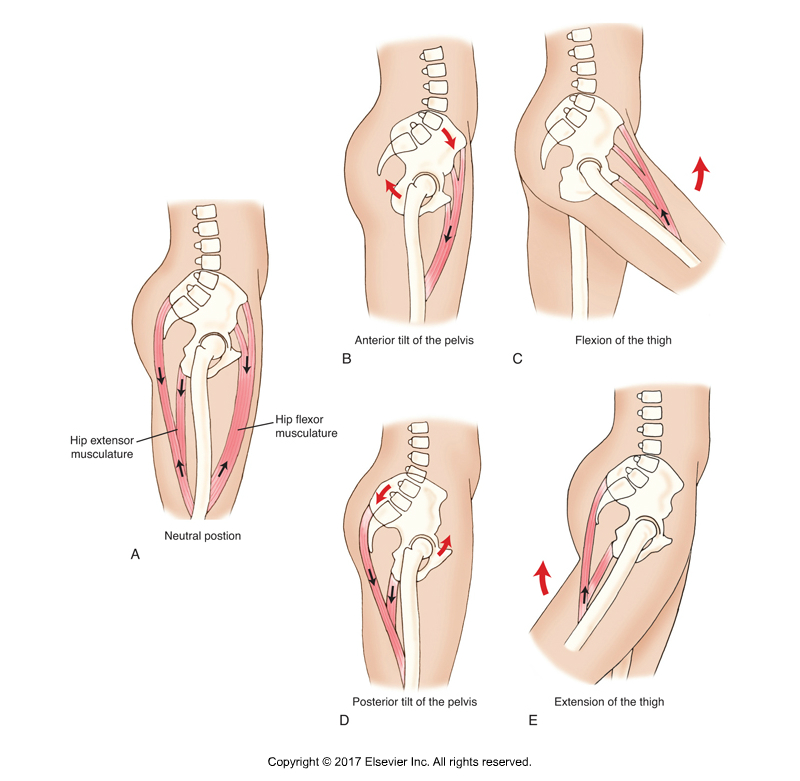

Standard and Reverse Actions at the Hip Joint. Permission Dr. Joe Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3ed. (Elsevier, 2017).

There are two groups of pelvic posterior tilters to strengthen. They are the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall mentioned earlier (rectus abdominis, external and internal abdominal obliques) that do flexion of the lumbar spine (because posterior tilt of the pelvis relative to the lumbar spine is the closed-chain reverse action of flexion of the lumbar spine) and hip extensors (because posterior tilt of the pelvis at the hip joint is the closed-chain reverse action of extension of the thigh at the hip joint), which are the posterior fibers of the gluteal muscles and the hamstrings. There are two groups of pelvic anterior tilters that need to be stretched/lengthened. They are the lumbar spinal extensors (because anterior tilt of the pelvis relative to the lumbar spine is the closed-chain reverse action of lumbar spinal extension) mentioned earlier (paraspinal erector spinae and transversospinalis musculature, and quadratus lumborum) and hip flexors (because anterior tilt of the pelvis is the closed-chain reverse action of flexion of the thigh at the hip joint).

Strengthen and Stretch Sagittal Plane Pelvic Tilters

So what we need to do is focus on strengthening the relatively weaker “locked long”(overly inhibited) posterior tilt musculature, the anterior abdominal wall and glutes and hamstrings. And we need to focus on stretching the relatively tighter/stronger “locked short” (overly facilitated) anterior tilters, the low back paraspinals and hip flexors.

Other Factors

Of course, if a client presents with the opposite distortion pattern of having a relatively posteriorly tilted pelvis (a sacral base angle markedly less than 30 degrees), with a hypolordotic lumbar spine and hypokyphotic thoracic spine (essentially a flat spine/back), then we would not look to further lessen their curves. Posturally, their spine does not need to be lengthened.

Scoliosis. Permission Dr. Joe Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach (LWW, 2015).

Also, there are a few other factors that matter when looking to create elongation of the spine. One is that hanging, which causes a long axis stretch to the spine, in other words, traction, will also help to lessen the sagittal plane curves of the spine. Another factor is the frontal plane posture of the spine. In the frontal plane, the spine should be straight. But if the client has a frontal plane curve (technically a scoliosis), then frontal plane curves would also shorten the spine and should be addressed to lengthen and elongate the spine.

Other factors, such as proper nutrition and hydration are also important toward creating elongation of the spine. Much of the height/length of our spine is created by the thickness of our discs, so if we are not well hydrated, then our discs would thin, and we would lose height/elongation.

Conclusion

The thrust of this article is to emphasize that the major focus when looking to create elongation of the spine should be to lessen the thoracolumbar curves. This can be accomplished by directly addressing the lumbar and thoracic curves, and by addressing the sagittal plane posture of the pelvis.

(Click here for the blog post article: Lower Crossed Syndrome.)

Digital COMT

Did you know that Digital COMT (Digital Clinical Orthopedic Manual Therapy), Dr. Joe Muscolino’s continuing education video streaming subscription service for manual therapists and movement professionals, has at present (January of 2019) more than 1,000 video lessons on manual and movement therapy continuing education, including entire folders on massage therapy, stretching, joint mobilization, fitness, Pilates, and yoga. And we add seven (7) new videos lessons each and every week! And nothing ever goes away. There are also folders on Pathomechanics and Anatomy and Physiology, including an entire folder on Cadaver Anatomy… and many, many more on other manual and movement therapy assessment and treatment techniques? Click here for more information.