Scoliosis is, by definition, a lateral flexion deformity of the spine. Although the spine should have curves in the sagittal plane, in the frontal plane, it should ideally be straight. Any curve that is present in the frontal plane is a scoliosis.

Note: This blog post article is the ninth in a series of twelve articles on musculoskeletal conditions of the low back (lumbar spine) and pelvis. For the rest of the articles in the series, scroll to the end of this article.

Description of Scoliosis

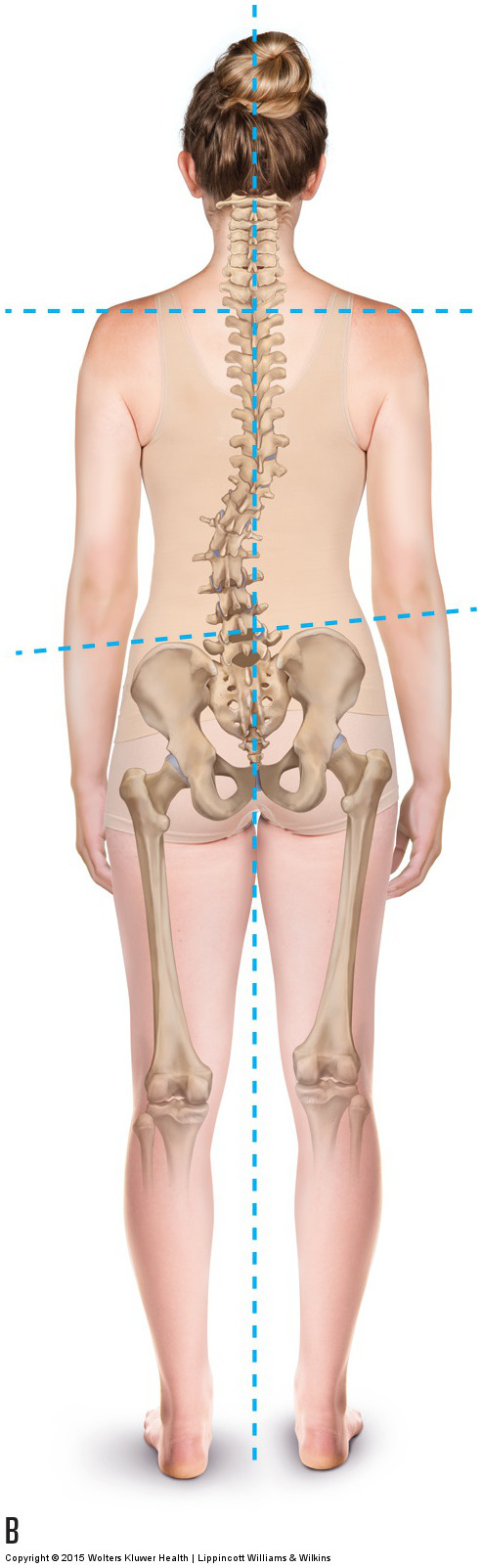

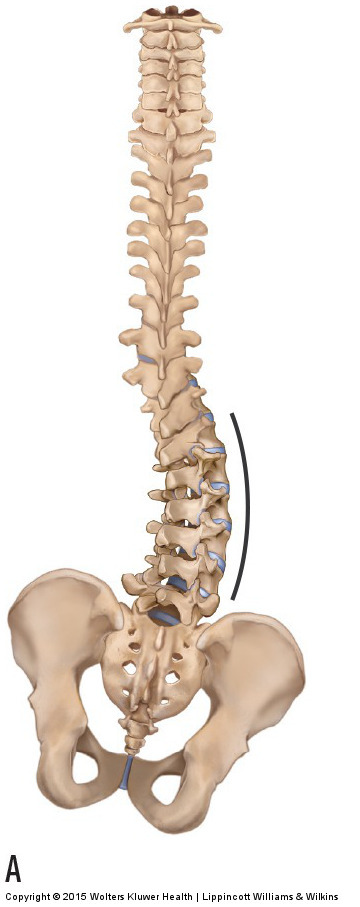

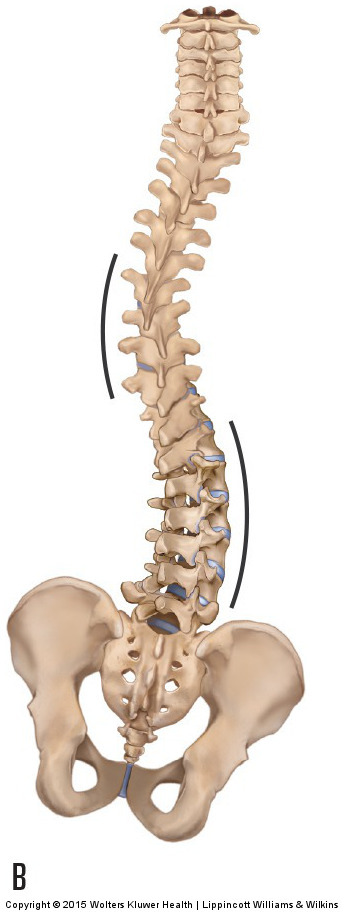

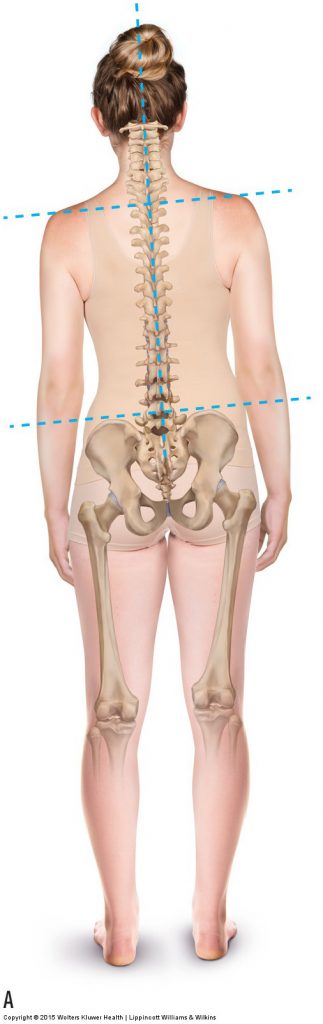

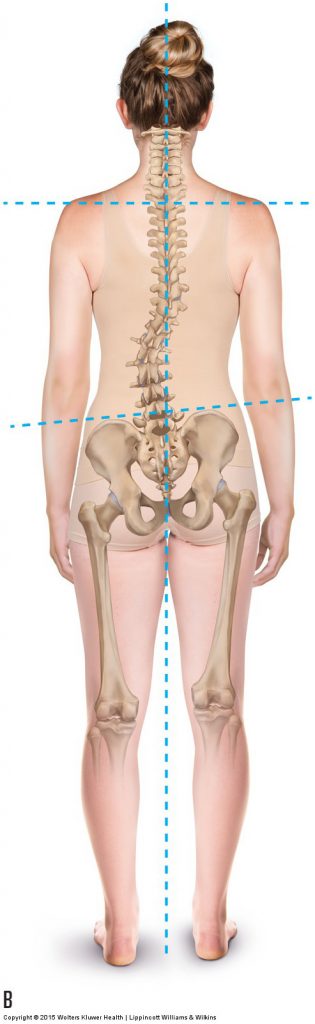

Figure 18. Scoliotic curves. (A) C-curve. (B) S-curve. (C) Double S-curve. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach. 2015.

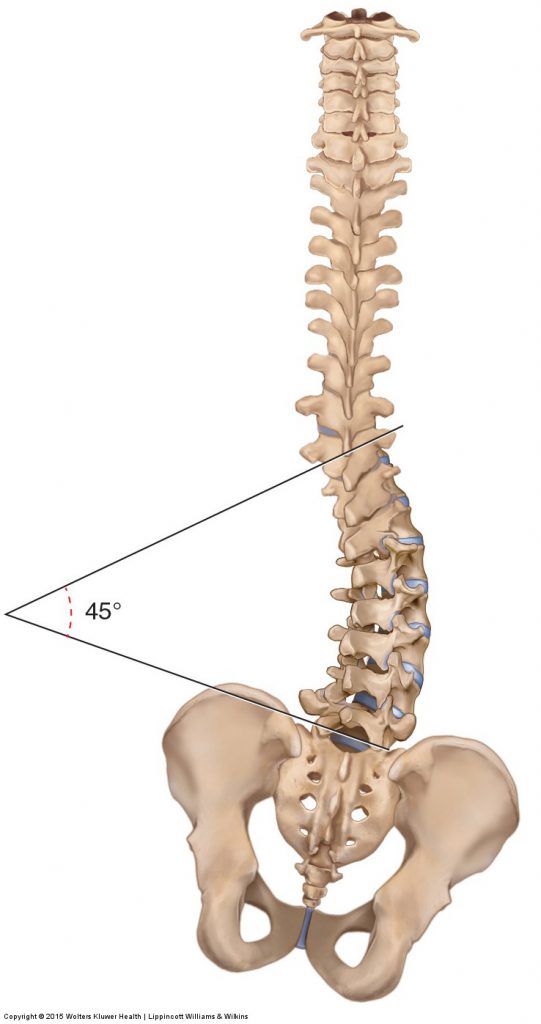

The shape of a scoliotic curve is usually described as being a C-curve, an S-curve, or a double S-curve (Fig. 18). Further, like most conditions, a scoliosis can be mild in presentation or more severe. The severity of a scoliotic curve can be measured by drawing a line along the superior surface of the body of the uppermost vertebra of the scoliotic curve and another line along the inferior surface of the body of the lowermost vertebra of the scoliotic curve, and then measuring the angle that is created by their intersection (Fig. 19). It is also important to note that although scoliosis is defined by its frontal plane lateral flexion, transverse plane rotation is also present. In the lumbar spine, facet joint lateral flexion couples with contralateral rotation; this results in the spinous processes rotating into the concavity of the curve (see Fig. 2-35). This coupled rotation can have repercussions during the postural assessment exam because if the therapist uses visualization of the spinous processes to assess the degree of scoliosis, when the spinous processes rotate into the concavity, the degree of scoliosis appears to be less (Fig. 20). For this reason, when possible, it is best to view an x-ray to determine the degree of a client’s scoliosis.

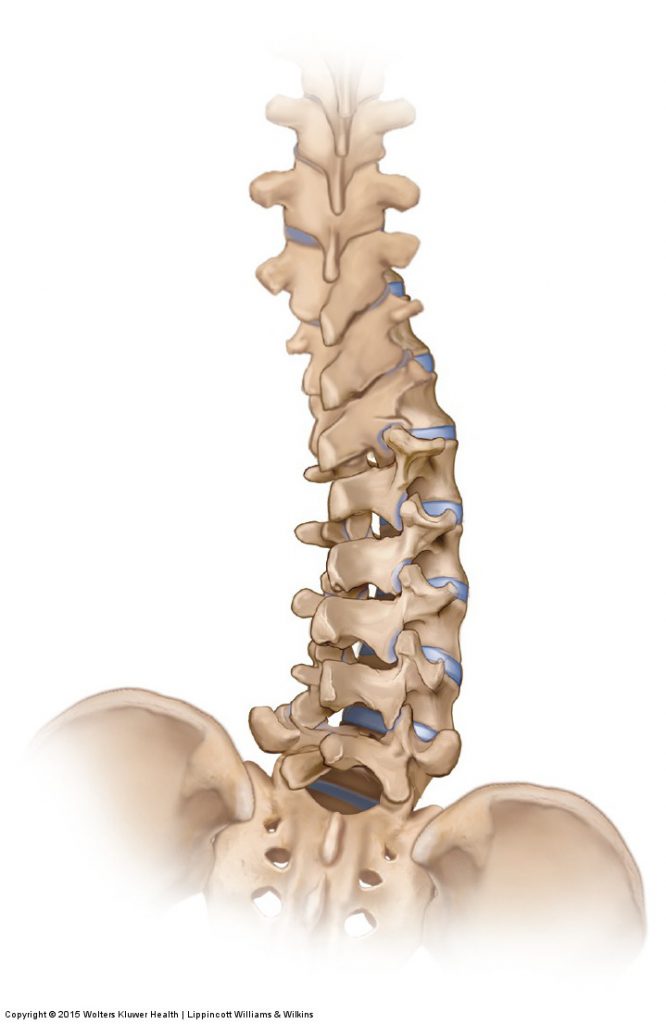

Figure 19. A scoliotic curve can be measured by drawing a line along the superior margin of the body of the upper vertebra of the curve, another line along the inferior margin of the body of the lower vertebra of the curve, and then measuring the angle formed by their intersection. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach. 2015.

Figure 20. In the lumbar spine, the spinous processes rotate into the concavity of a scoliosis, making the scoliosis less evident during visual examination. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach. 2015.

Mechanism and Causes of Scoliosis

The curvature of the lumbar spine is largely determined by the posture of the pelvis. The 5th lumbar vertebra sits on the base of the sacrum of the pelvis; therefore, if the sacrum changes its posture, the lumbar spine must accordingly change its posture. If the sacrum tilts in the frontal plane, then like the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the spine will lean to that side. This would result in the head being unlevel, and therefore the eyes and inner ears being unlevel, throwing off our sense of balance and making it difficult to see. To compensate, the spine bends in the frontal plane to bring the head back to level, thereby creating a scoliotic curve (Fig. 21). A number of factors can unlevel the sacrum. A tight quadratus lumborum could pull the pelvis and sacrum up on one side; similarly, tight hip abductors (e.g., gluteus medius) could pull the pelvis and sacrum down on one side. An anatomically short femur or tibia can create a lower extremity that is shorter on one side than the other, dropping the pelvis/sacrum on that side. Excessive pronation of the foot, resulting in a dropped arch, can also result in a shorter lower extremity on that side.

Figure 21. Scoliosis as a compensation for unlevel sacral posture. (A) If the sacrum is unlevel in the frontal plane, the spine would slant to the side where the sacrum is low. This results in the head, and therefore the eyes and inner ears being unlevel. (B) As a compensation, a scoliotic curve of the spine brings the eyes and inner ears to be level. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach. 2015.

Sometimes, the cause of a scoliotic curve is unknown. Idiopathic scoliosis, which usually occurs in adolescent girls and is often quite severe, has no known cause (idiopathic literally means “of unknown origin”). Regardless of the cause, it is important to treat scoliosis because it can continue to progress throughout a person’s life, often increasing between one-half and one degree per year.

Note: Scoliosis and Tight Muscles

Muscles are usually tight on both sides of a scoliotic curve. The muscles are lengthened and tight on the convex side (often termed “locked long”) and shortened and tight on the concave side (often termed “locked short”). Although it is important to work both sides, it is especially important to work the shortened concave-side muscles with massage and stretching and to work the lengthened convex-side muscles with massage and strengthening exercise.

Note: Treatment Considerations in Brief for Scoliosis

Moist heat, massage, and stretching can be very beneficial for clients with scoliosis. When stretching, it is important that the client focus the stretch so that the lateral flexion component of the stretch is opposite to the concavity of the curve. In other words, if the concavity is oriented to the right, the stretch should be into left lateral flexion.

This blog post article is the ninth in a series of twelve articles on musculoskeletal conditions of the low back (lumbar spine) and pelvis.

The articles in this series are:

- Hypertonic / tight muscles

- Myofascial trigger points

- Joint dysfunction

- Sprains and strains

- Sacroiliac joint injury

- Pathologic disc conditions and sciatica

- Piriformis syndrome

- Degenerative joint disease (DJD)

- Scoliosis

- Lower crossed syndrome

- Facet syndrome

- Spondylolisthesis