Ligaments of the Lumbar Spine and Pelvis

This blog post article is an overview of the ligaments of the lumbar spine and pelvis.For more complete coverage of the structure and function of the low back and pelvis, Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3rd ed. (2017, Elsevier) should be consulted.

As with the muscles, it is also helpful to know the ligaments of the lumbar spine and pelvis to be able to effectively stretch the client. Whatever technique is used, the purpose of stretching is to loosen all soft tissues that are taut and restricting joint motion. Even though the function of a ligament is to stabilize and limit motion of the bones to which it attaches, a taut ligament can be just as culpable as a tight muscle in excessively restricting the motion of a joint. Therefore, when a client presents with a tight low back, a basic knowledge of the ligaments of the lumbar spine and pelvis is valuable.

The “action” of a ligament is similar to that of an antagonist muscle. If an antagonist muscle is tight, it restricts motion that is opposite that of its mover action(s). For example, if a trunk extensor (located posteriorly) is tight, it restricts motion of the trunk anteriorly into flexion. Because the limited motion is usually to the side of the body opposite the side on which the muscle is located, antagonist muscles are sometimes called contralateral muscles; contralateral literally means opposite side. Similarly, ligaments tend to be located contralaterally, on the other side of the joint from the motion that they limit.

For example, if the trunk resists moving into flexion, the taut ligaments that would restrict this motion are located posteriorly (where antagonist trunk extensor muscles are located). If the motion that is limited is right lateral flexion of the trunk, the taut ligaments limiting this motion would be located in the left side of the trunk (where antagonist left lateral flexor muscles are located) (Fig. 44).

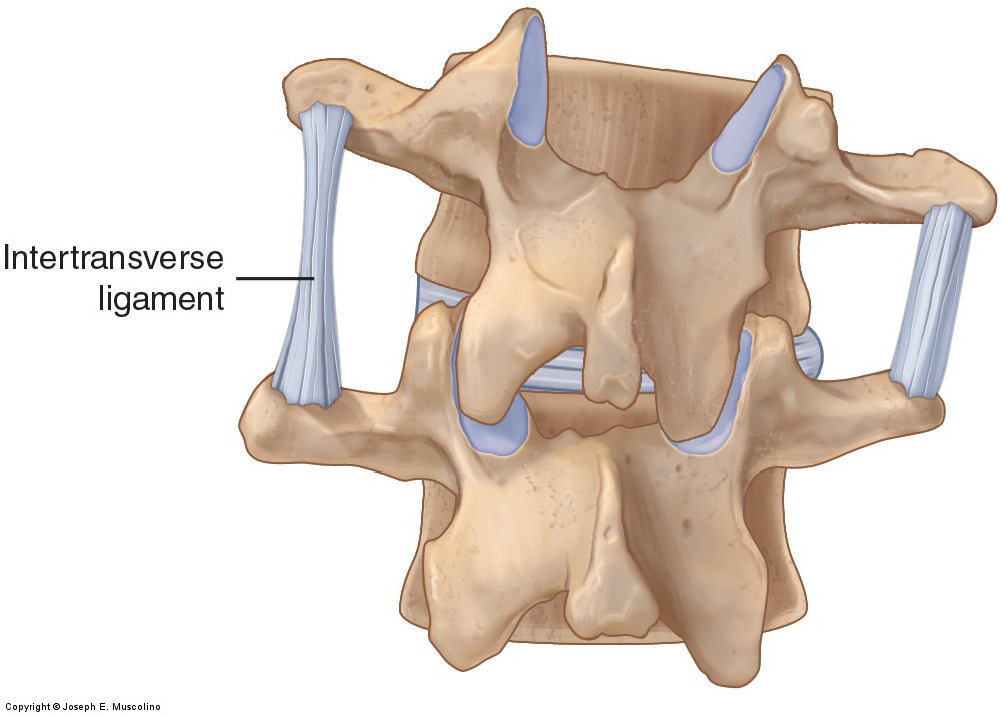

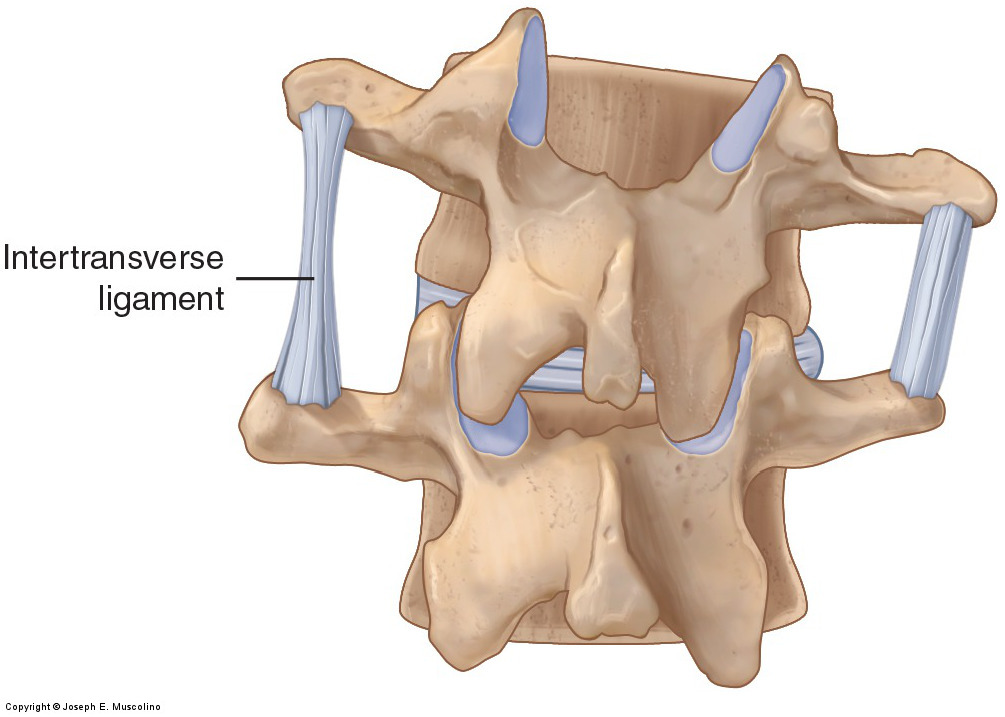

Figure 44. Ligament function. Posterior view of two vertebrae that illustrates how a ligament becomes taut and limits motion of the bones of a joint in the direction opposite the ligament’s location. In this example, when the superior vertebra right laterally flexes, the intertransverse ligament located on the left side becomes taut and limits this motion. Courtesy Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach (2015).

As is typically the case, rotation is a bit trickier. Just as muscles that perform rotation may be on either side of the body in relation to the rotation they create, ligaments that restrict right or left rotation can also be located on either side of the body. Similar to musculature, determining a ligament’s role in restricting rotation can best be seen by looking at how the ligament (partially) “wraps” around the body part in the transverse plane.

Ligaments of the Lumbar Spine

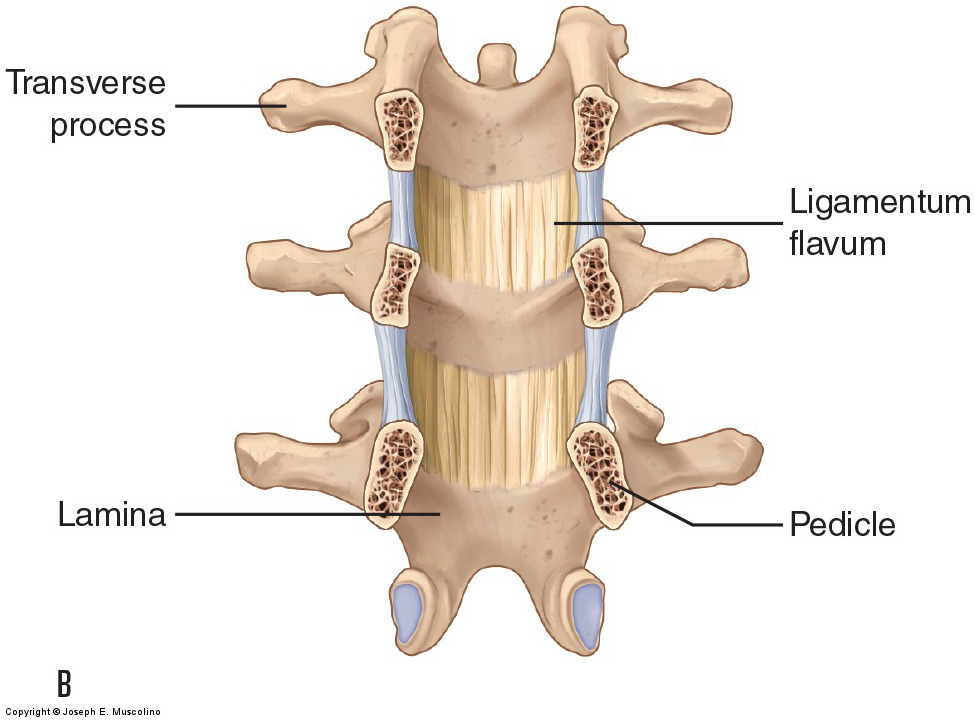

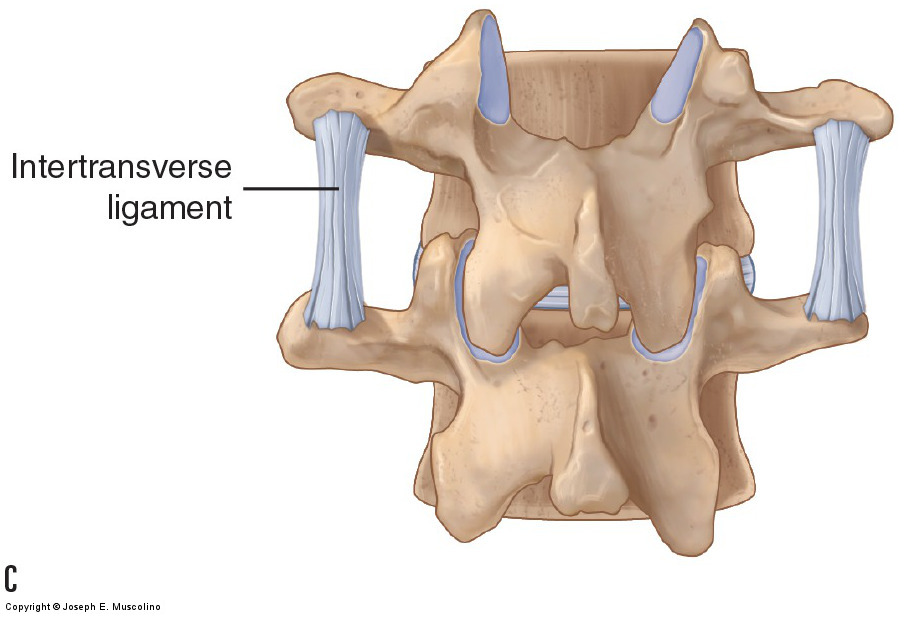

The major ligaments of the lumbar spine are shown in Figure 45. The supraspinous ligament, interspinous ligaments, fibrous capsules of the facet joints (which are ligamentous in structure and therefore also function to limit motion), ligamentum flavum, and posterior longitudinal ligament are all located posterior to the axis of motion for flexion and extension of the spine; therefore, they all limit flexion. The anterior longitudinal ligament is located anterior to the axis of motion for flexion and extension of the spine; therefore, it limits extension. The intertransverse ligaments are located laterally. They limit lateral flexion to the opposite side of the body (contralateral lateral flexion) from where they are located. Many of these ligaments also act to limit rotation of the lumbar spine to one side or the other.

Figure 45. Ligaments of the spine. (A) Right lateral view of a sagittal plane cross section through the spine. (B) Anterior view of a frontal plane section through the pedicles of the spine in which the ligamentum flavum inside the spinal canal can be seen. (C) Posterior view depicting the intertransverse ligaments. Courtesy Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach (2015).

(Note: Click here for an article on the ligaments of the cervical spine.)

Note: Thoracolumbar Fascia and Abdominal Aponeurosis

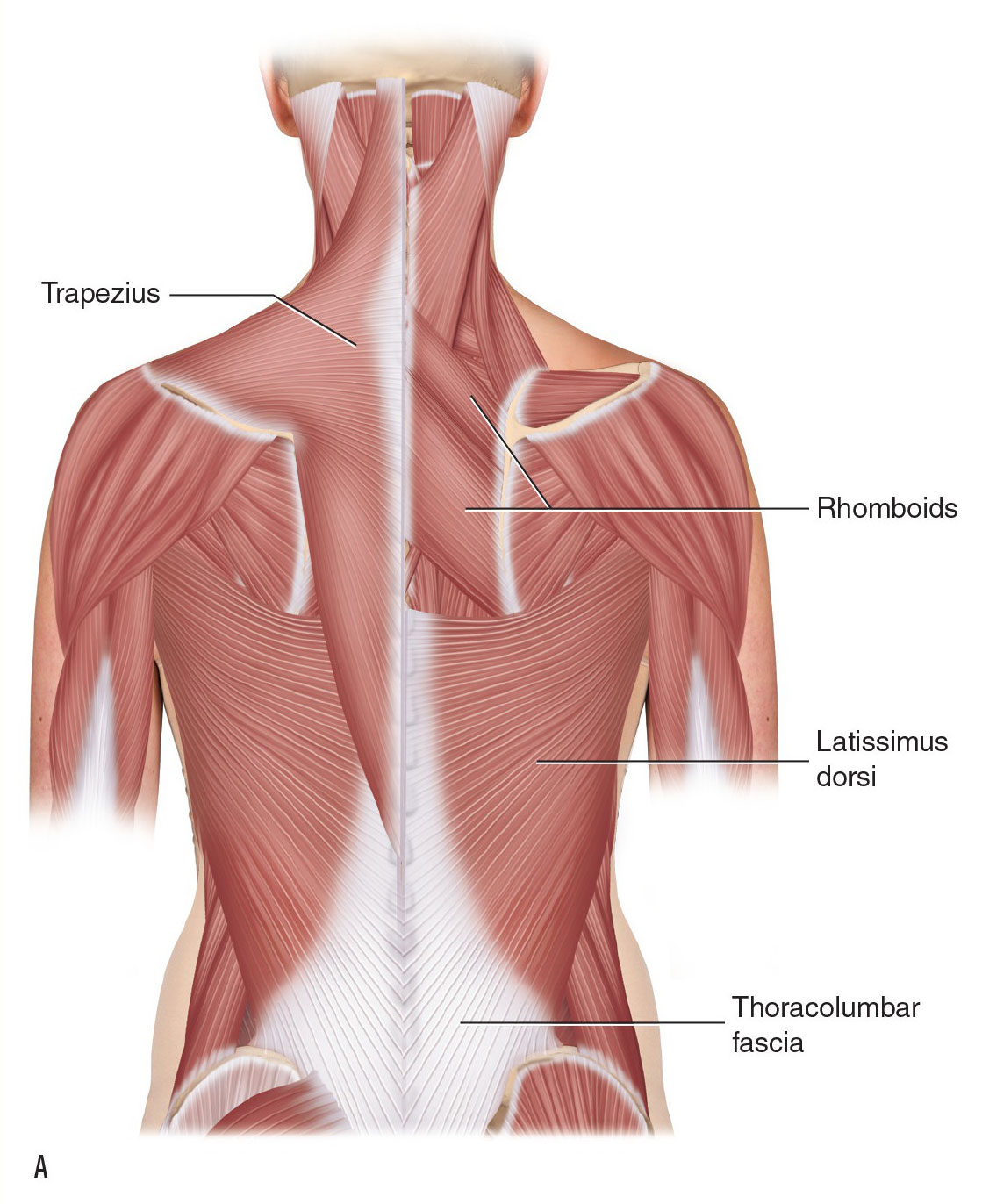

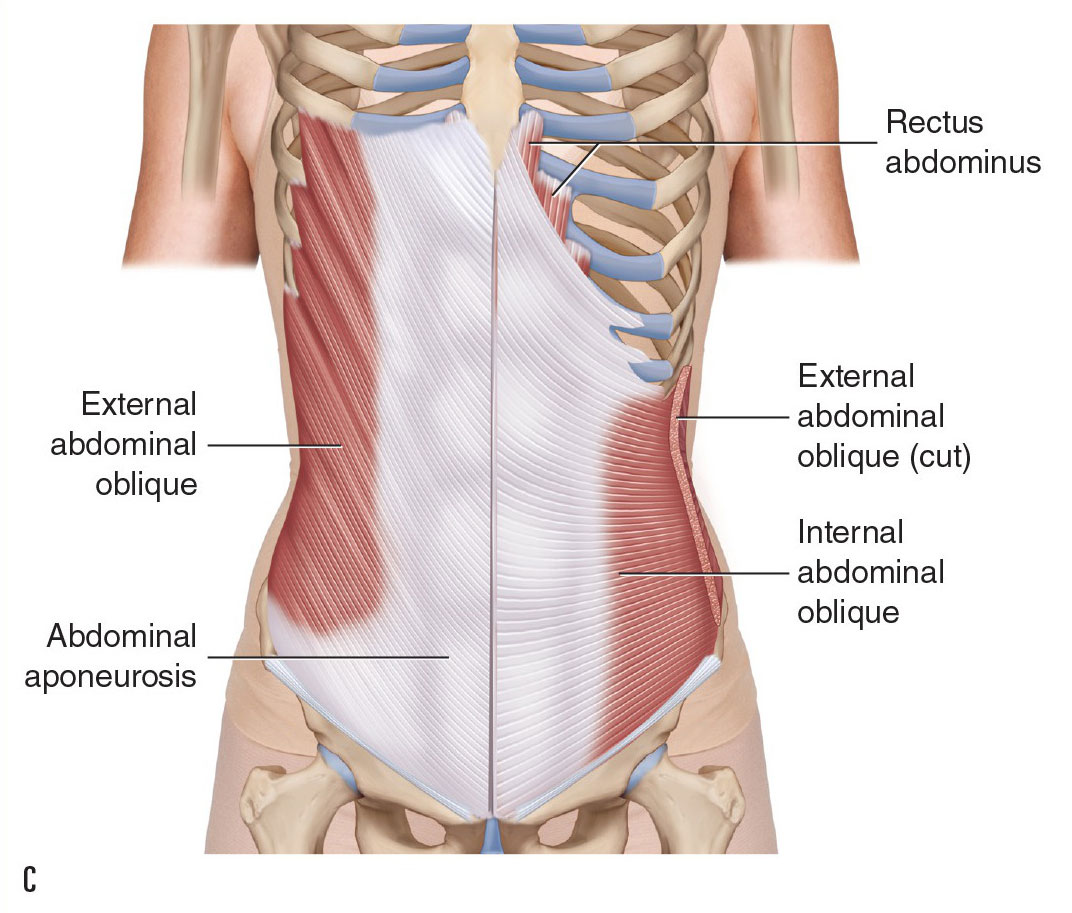

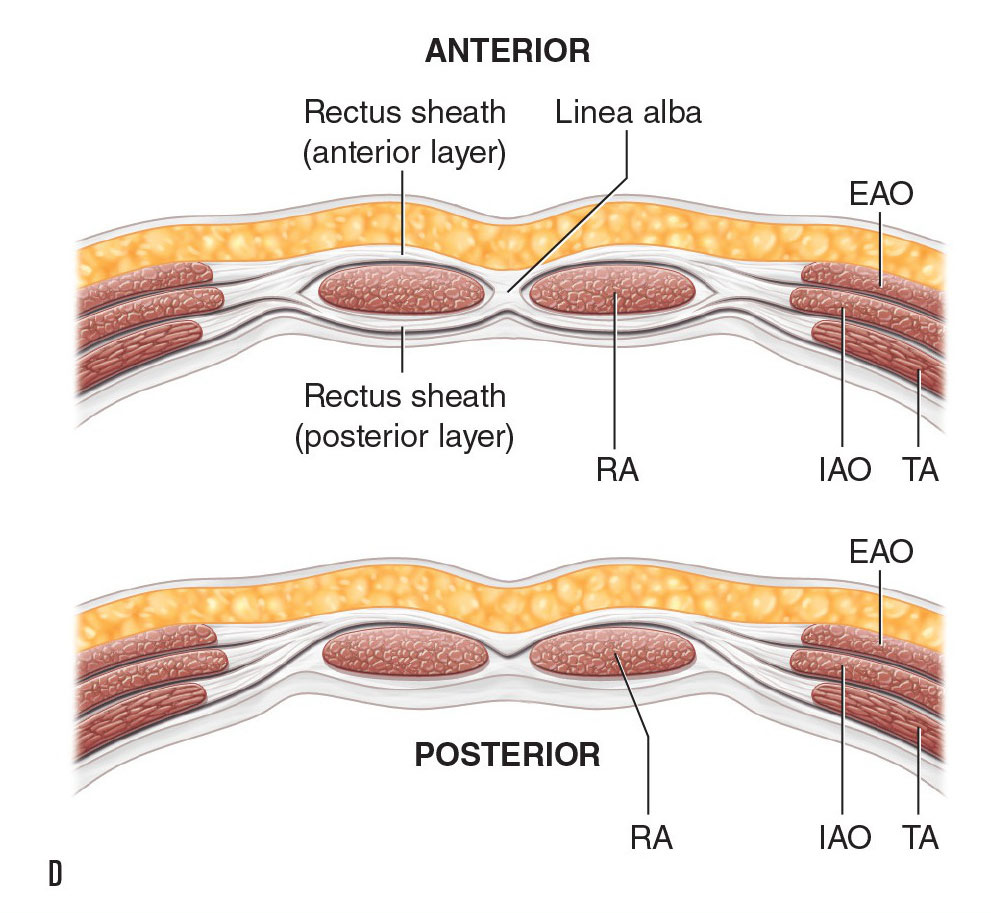

In addition to the fibrous fascial ligaments and joint capsules of the lumbosacral and sacroiliac region, further stabilization is provided by the thoracolumbar fascia posteriorly and the abdominal aponeurosis anteriorly. The thoracolumbar fascia is well developed in the lumbar region where it divides to form three layers: a posterior layer superficially, a middle layer between the erector spinae and transversospinalis musculature and the quadratus lumborum, and a deep anterior layer between the quadratus lumborum and psoas major (see Figs. A and B). The abdominal aponeurosis is created by the anterior aponeuroses of the external and internal abdominal obliques (EAO and IAO) and transversus abdominis (TA) muscles and forms a sheath around the rectus abdominis musculature (see Figs. C and D). (Note: The abdominal aponeurosis does not totally ensheathe the rectus abdominis at its inferior end, as seen in the lower figure of D.)

Thoracolumbar fascia (A) Posterior view. (B) Transverse plane cross-section view. Abdominal aponeurosis. (C) Anterior view. (D) Transverse plane cross-section views. Upper figure: upper trunk. Lower figure: lower trunk. EAO, external abdominal oblique; IAO, internal abdominal oblique; SP, spinous process; TA, transversus abdominis; TP, transverse process.

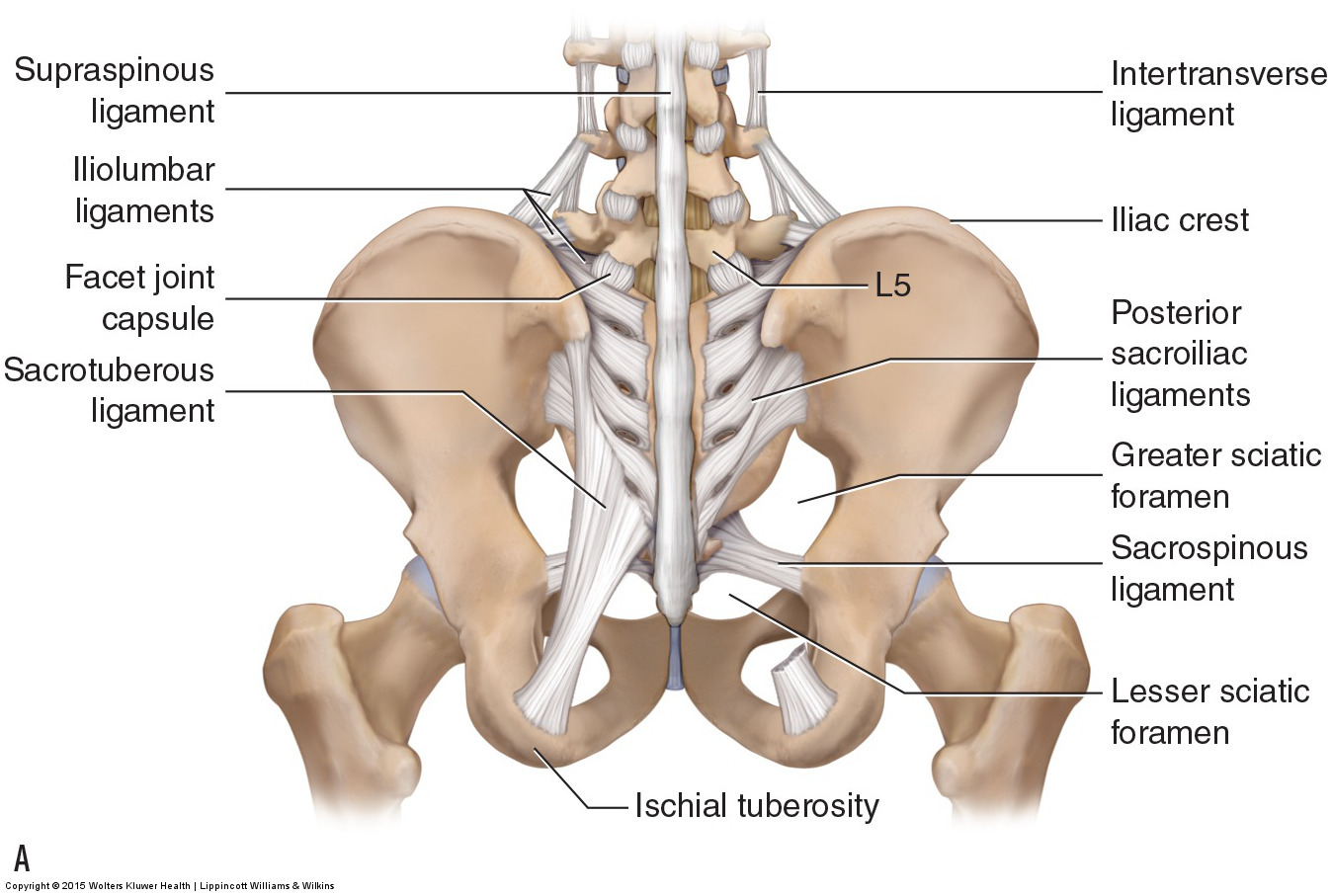

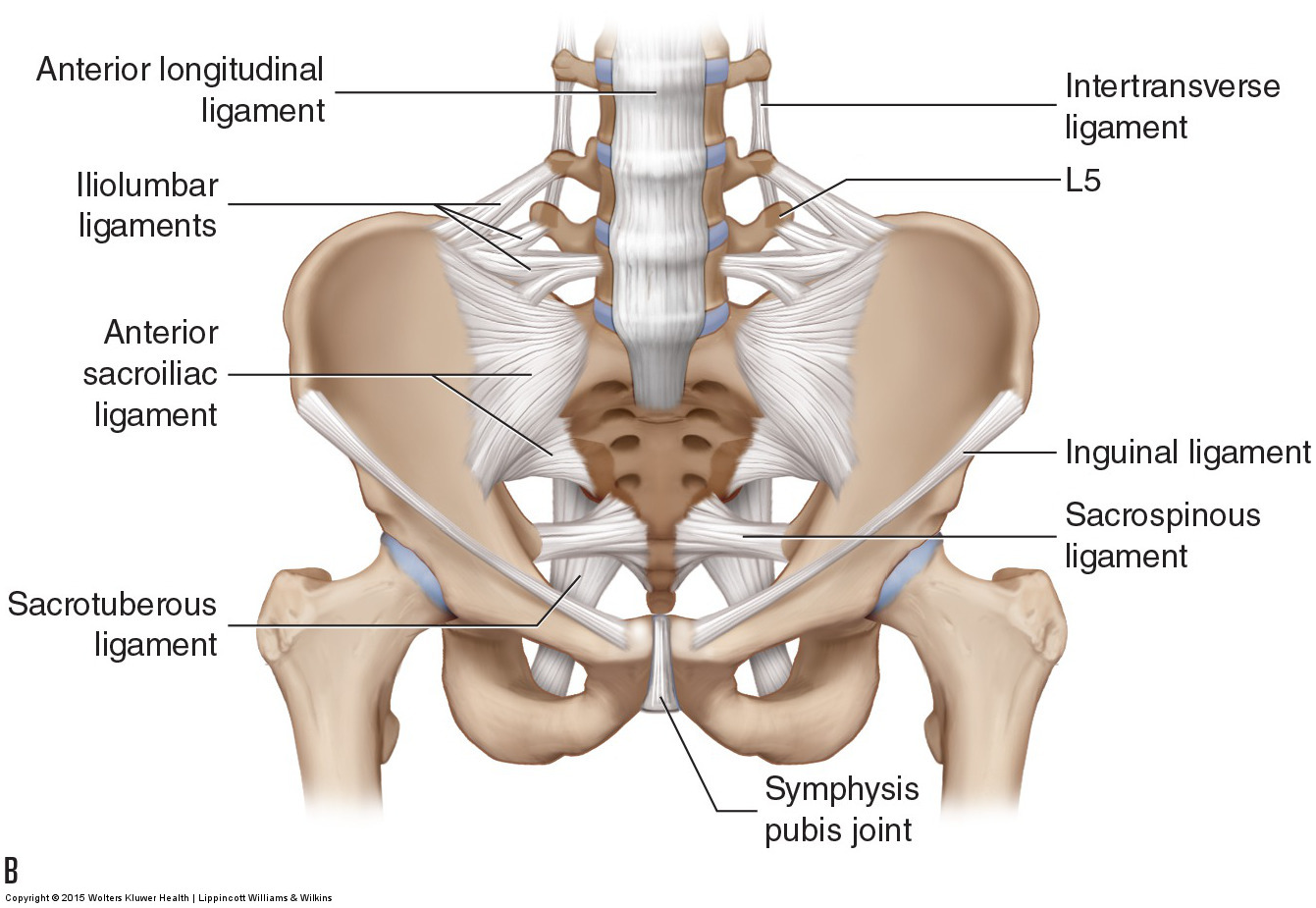

Ligaments of the Pelvis

The bones of the pelvic girdle are well supplied with ligaments for stabilization (Fig. 46). Most lumbar spinal ligaments continue down to connect the lumbar spine to the sacrum and pelvic bones. The iliolumbar ligaments can be viewed as extensions of the intertransverse ligaments between L4 and the pelvis and L5 and the pelvis. Within the pelvis itself, copious ligaments provide stabilization to the SIJ, both posteriorly and anteriorly. Besides the posterior sacroiliac ligaments and anterior sacroiliac ligaments that attach directly from the sacrum to the pelvic bone on each side, note the strong and powerful sacrotuberous ligament and sacrospinous ligament posteriorly.

Figure 46. Ligaments of the pelvis. The SIJ is well stabilized posteriorly and anteriorly by ligaments. (A) Posterior view. (B) Anterior view. Courtesy Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach (2015).

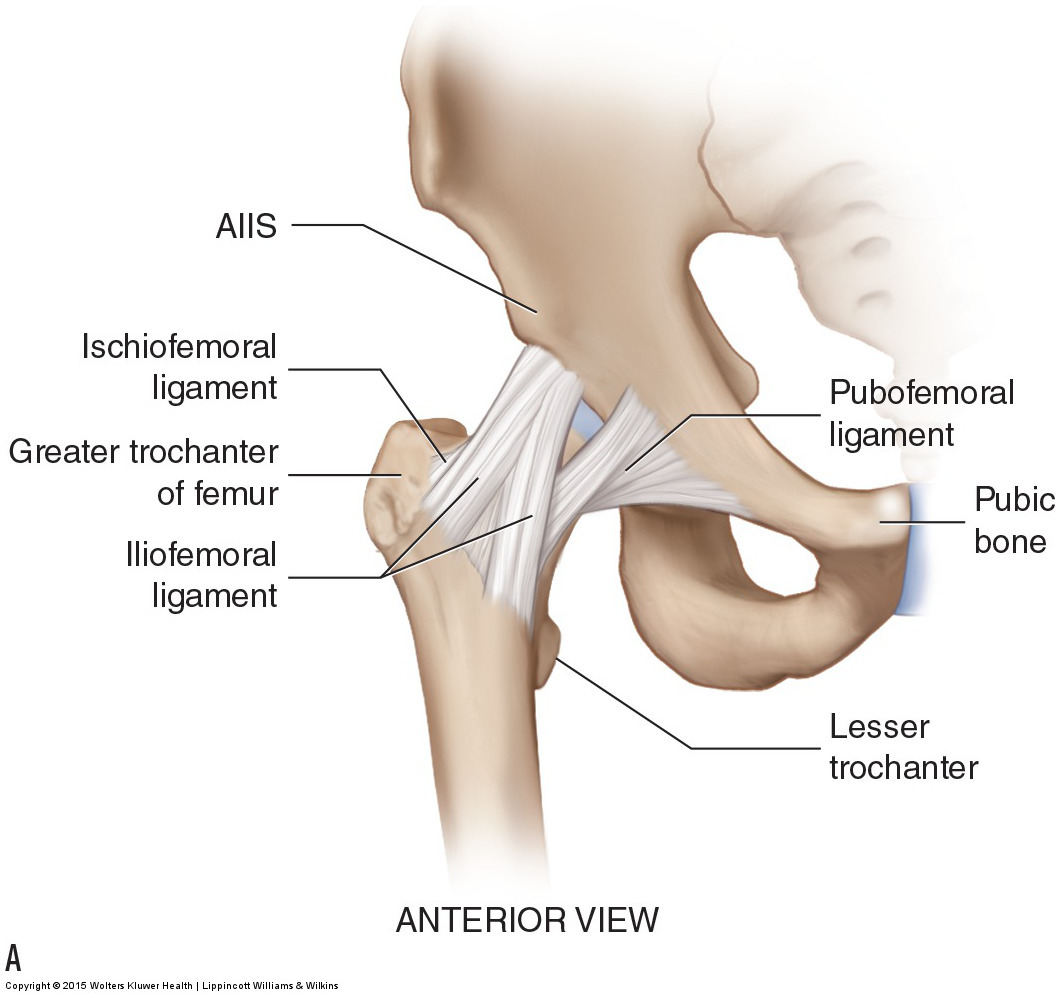

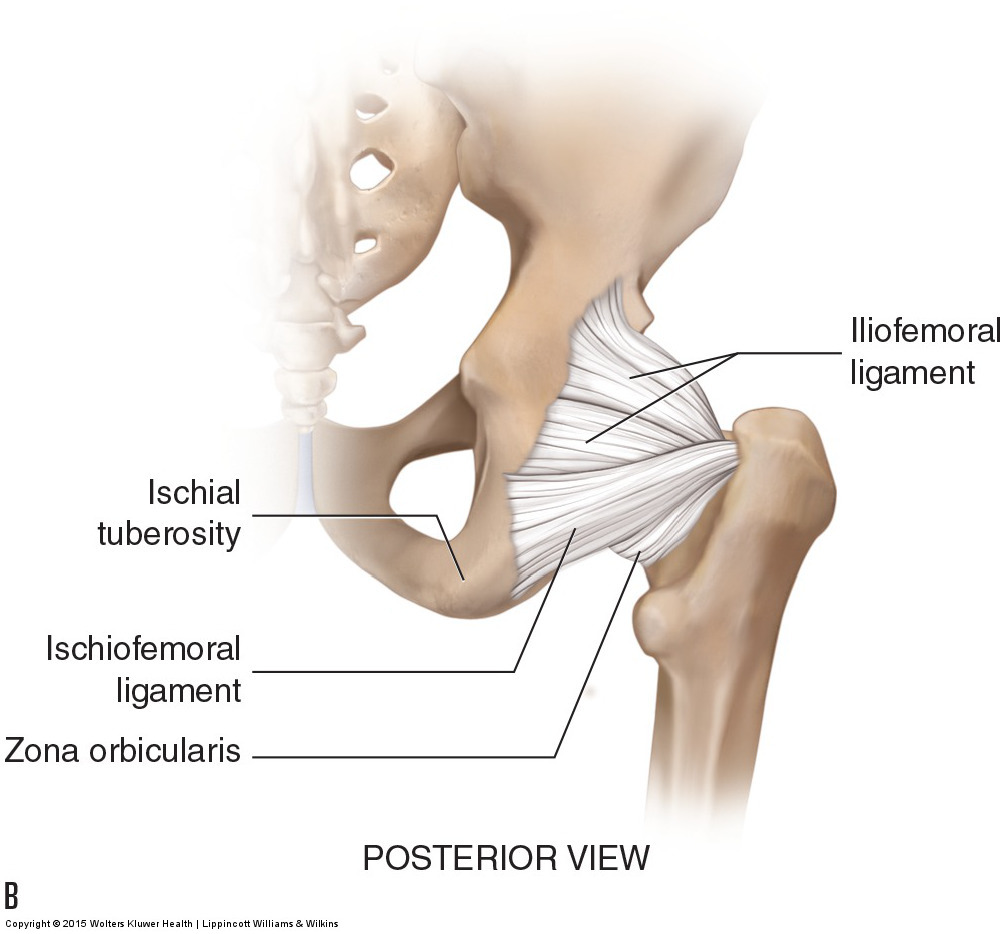

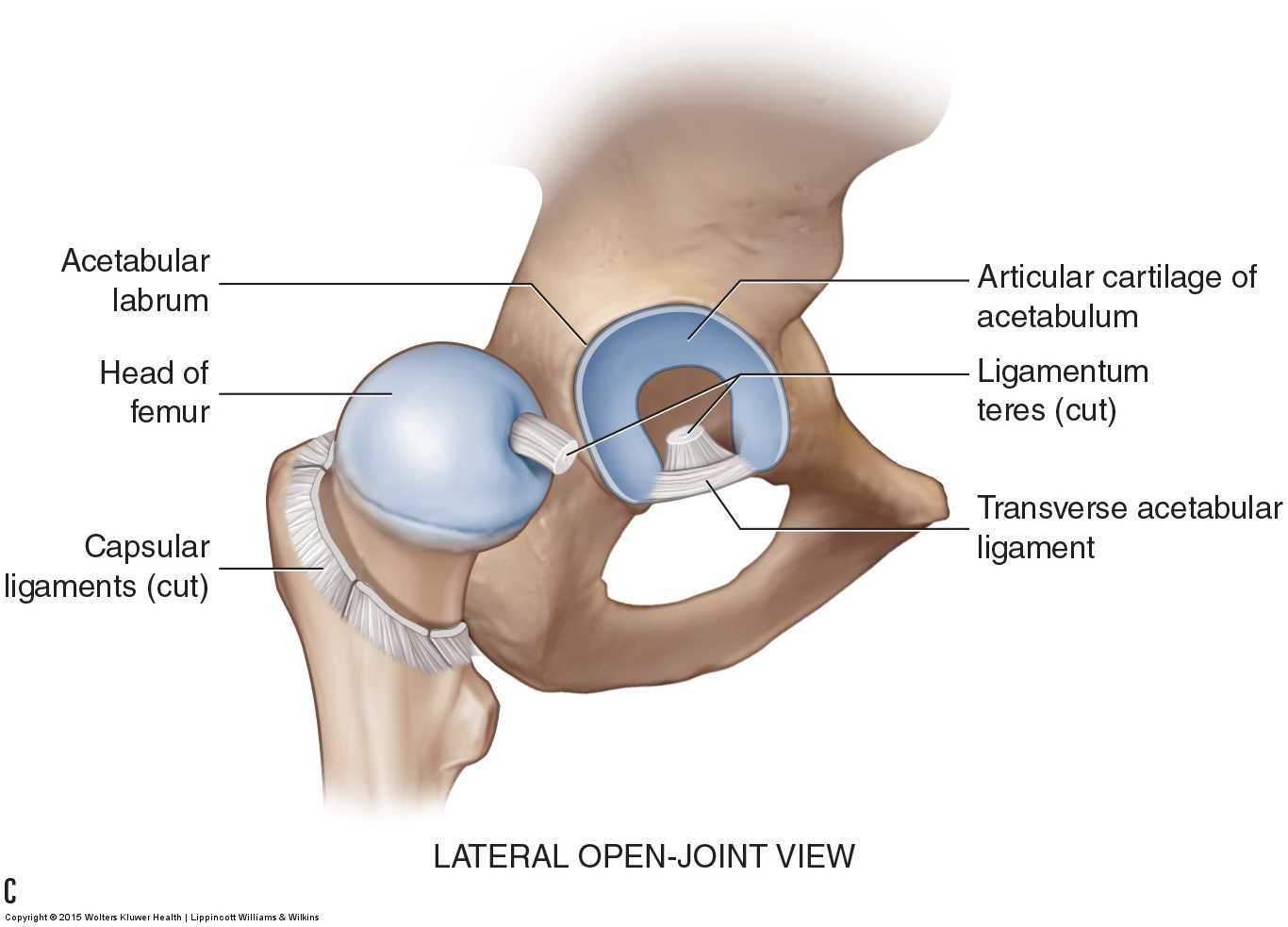

Ligaments of the Hip Joint

Connecting the pelvic bone to the femur on each side are the ligaments of the hip joint. The fibrous capsule of the hip joint is reinforced by three capsular ligaments: the iliofemoral ligament anteriorly, the ischiofemoral ligament posteriorly, and the pubofemoral ligament medially (Fig. 47). The iliofemoral ligament primarily limits extension of the thigh and posterior tilt of the pelvis at the hip joint. The ischiofemoral ligament, due to its horizontal wrapping around the joint, primarily limits medial rotation of the thigh and ipsilateral rotation of the pelvis at the hip joint. The pubofemoral ligament primarily limits abduction of the thigh and depression (lateral tilt) of the same-side pelvis at the hip joint. The joint capsule is reinforced near the neck of the femur; this area is termed the zona orbicularis. Internal within the joint is the ligamentum teres that connects the head of the femur to the acetabulum and limits axial distraction (traction) of the joint (see Fig. 47).

Figure 47. Ligaments of the hip joint. (A) Anterior view. (B) Posterior view. (C) Lateral open-joint view. AIIS, anterior inferior iliac spine. Courtesy Joseph E. Muscolino. Manual Therapy for the Low Back and Pelvis – A Clinical Orthopedic Approach (2015). ([C] Modeled from Neumann DA. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Physical Rehabilitation. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2010.)

Note: This is the seventh in a series of 8 blog post articles on the anatomy and physiology of the lumbar spine and pelvis.

The blog post articles in this series are:

- Bones of the Lumbar Spine and Pelvis

- Joints of the Lumbar Spine (disc & facet) and Pelvis

- Motions of the Joints of the Lumbar Spine

- Motions of the Joints of the Pelvis

- Muscles of the Lumbar Spine

- Muscles of the Pelvis

- Ligaments of the Lumbar Spine and Pelvis

- Precautions for Manual Therapy of the Lumbar Spine and Pelvis