What are the Manual Therapy Precautions and Contraindications when working the Neck?

The neck contains many structures whose locations are important to know for reasons of client safety. Many of these structures are sensitive neurovascular structures (nerves, arteries, and veins) that contraindicate pressure. Others are similarly sensitive structures that require gentle pressure. The majority of these structures are located anteriorly (Fig. 13).

For this reason, it is essential to exercise caution when working the anterior neck of a client. However, even though caution is called for, it should not prevent therapeutic work entirely, as happens with some therapists. This is unfortunate, because anterior neck work can be extremely valuable, especially to clients who have experienced a whiplash accident in the recent or distant past. Knowledge of the anatomy of the anterior neck can allow work to be performed therapeutically and safely. (Future blogs will discuss other cautions and contraindications for specific pathologic conditions.)

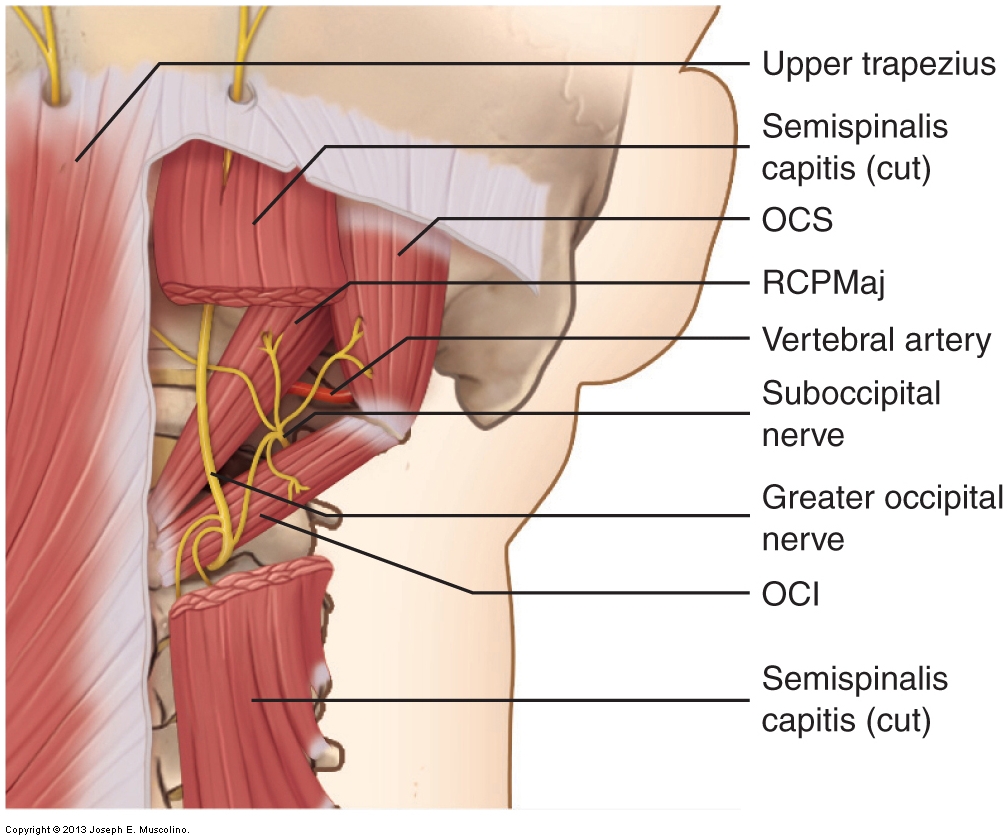

Figure 13. Structures of the anterior neck. Many anterior neck structures are sensitive; therefore, caution is required when working this region. The thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilages, trachea, and thyroid gland are located at midline. The common carotid artery and jugular vein are located slightly lateral to midline. The brachial plexus and the subclavian artery are located inferolaterally. (Courtesy of Joseph E. Muscolino.)

Anterior Structures: Common Carotid Artery and Jugular Vein

Most notably, the common carotid artery and jugular vein are located in the anterior neck, slightly lateral to midline, running inferiorly/superiorly. The following are some general precautions/guidelines for work in this area:

- Avoid working on these structures. It is usually easy to know when the fingers are pressing on the carotid artery because a pulse can be felt.

- When palpating for an artery, it is usually better to use a finger than the thumb because the thumb’s pulse is fairly strong and may be confused with the client’s pulse.

- Do not palpate too deeply for a pulse because it is possible to compress the artery and block its blood circulation, thereby blocking its pulse as well.

- If you detect the pulse of the client’s carotid artery while you are working on the area, do not stop working. Instead, either slightly move your palpating fingers, or gently displace the vessel to one side or the other and continue working in that spot.

The Carotid Sinus Reflex

In the common carotid artery in the anterior neck, the region called the carotid sinus (approximately halfway up the neck) contains stretch receptors that are located in the wall of the vessel. These receptors are involved in a neurologic reflex called the carotid sinus reflex, which can lower blood pressure. The mechanism works as follows. These stretch receptors are sensitive to stretching of the artery wall, which they interpret as coming from high blood pressure within the artery distending the artery wall outward. However, if the wall is stretched or distended inward (rather than outward) because of manual pressure, these stretch receptors are fooled into thinking that high blood pressure is causing the distortion of the vessel wall. Consequently, the stretch receptors trigger the reflex that results in lowering the client’s blood pressure. Although this can actually be used positively (e.g., intensive care nurses are trained to do this when a patient’s blood pressure is rising), it can also be seriously detrimental if the client is older and/or weak. Lowering the blood pressure excessively could cause the client to pass out and/or cause the heart to stop.

Anterior Structures: Midline

Located midline in the anterior neck are the thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilage, and trachea. The following are general precautions/guidelines for working near these structures:

- Do not place pressure on these structures. Note their location in the anterior midline of the neck. As with blood vessels, it is best to avoid these structures altogether.

- If the client is comfortable with your working in this area, you can gently displace these structures to the side (be aware, however, that moving or pressing on them may cause a cough reflex). For example, if you are working on the anteromedial neck musculature, such as the longus colli, it may be helpful to gently displace these structures toward the other side to allow full access to the musculature.

- Avoid the thyroid gland, which is located in the lower anterior neck.

- Use only light pressure over the hyoid bone. The hyoid bone is located more superiorly in the anterior neck and serves as an attachment site for many muscles. Although the attachments of these muscles on the hyoid bone can and should be worked, the pressure used should not be very deep.

Anterior Structures: Brachial Plexus and Subclavian Artery

Located inferiorly and laterally in the anterior neck are the brachial plexus and the subclavian artery. These structures pass between the anterior and middle scalene muscles and then continue inferolaterally to pass deep to the clavicle. If appreciable pressure is placed on the brachial plexus, the client will often report a shooting pain that runs into and/or down the same-sided upper extremity. This is likely to happen when doing deep specific work to the scalenes. Guidelines for working the scalenes in the lower anterior neck are as follows:

- Begin with light to medium pressure before transitioning to deeper pressure.

- If pressure on the scalenes causes the client to experience referral of pain or some other sensory disturbance (e.g., tingling) down into the upper extremity, slightly change the location of your pressure because you might be placing your pressure directly on the brachial plexus nerves.

Therapist Tip: Scalene Work and Referral Symptoms

- Pain or other referral symptoms experienced into the upper extremity when applying pressure to the scalenes can result from pressure directly on the brachial plexus. However, pressure to the scalenes can also refer symptoms into the upper extremity because of trigger point (TrP) referral. Therefore, it can be difficult to be certain of the cause of the referral. Referral caused by direct nerve pressure tends to feel like a shooting pain; however, this is not always the case. Consulting a TrP referral illustration may help (see Chapter 2 for illustrations of TrPs and their referral zones). If your client’s pain falls within the typical TrP referral pattern, it is more likely that the pain is a TrP referral, but this is not definite. If the referral does not coincide with the typical TrP referral pattern, then you are most likely pressing directly on the brachial plexus and should move your pressure slightly so as to remove pressure from the nerves. When in doubt, it is always wise to be cautious and change the location of your pressure.

Lateral Structures: Transverse Processes

The transverse processes of the cervical spine have already been discussed, but it is worthwhile to mention them again in the context of precautions and contraindications when working the neck. The transverse processes are split into anterior and posterior tubercles whose sharp points make them very sensitive to your pressure. If you are massaging the attachments of the scalenes or other muscles, it may be necessary for you to work the soft tissue attachments that are directly on the transverse processes. If this is the case, it is essential to consider their sensitivity and adjust your pressure accordingly. However, never use the transverse processes as contact points when administering a force to stretch or perform joint mobilization of the neck. There is no justification for this. Stretching and joint mobilization are better and more comfortably accomplished by contacting the articular processes and laminar groove of the client’s cervical spine.

Posterior Structures

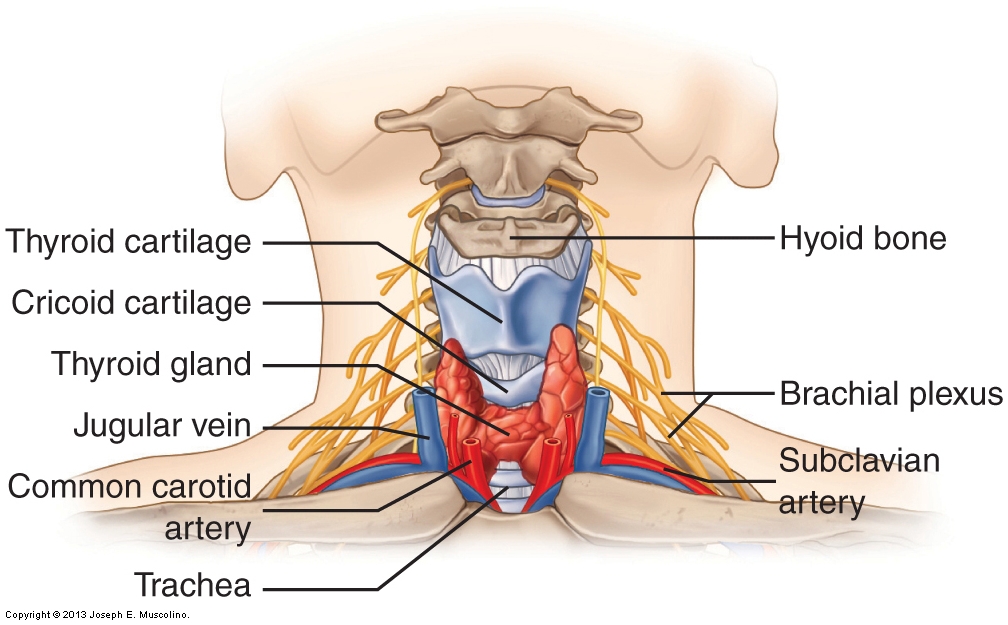

In the posterior neck, be aware of the location of the suboccipital nerve and vertebral artery (Fig. 14). These two structures are located in the suboccipital triangle, the triangular space bordered by the rectus capitis posterior major and obliquus capitis inferior and superior muscles. Further, the greater occipital nerve is also present in this region. Although deep tissue work in the posterior upper neck can be extremely valuable and may be necessary for the client, it is essential to take into consideration the location of these nerves and this artery when performing such work.

Figure 14. Neurovascular structures of the posterior neck. The suboccipital and greater occipital nerves and vertebral artery are demonstrated. Caution should be exercised when working in the upper posterior cervical region. OCI, obliquus capitis inferior; OCS, obliquus capitis superior; RCPMaj, rectus capitis posterior major. (Courtesy of Joseph E. Muscolino.)

Precaution with Extension and Rotation Motions

Another caution should be mentioned, even though it does not involve an anatomic structure per se. When treating a client’s neck, be aware that many clients do not tolerate well any extension beyond anatomic position and/or any extreme or fast rotation motions. This is especially true with elderly clients, but it may also be true for middle-aged or younger clients, especially if they have recently experienced a traumatic neck injury. For this reason, it is always wise to be aware of this possibility. It is advisable to increase these ranges of motions gradually over the span of several visits if necessary.

(All figure credits: Courtesy of Joseph E. Muscolino. Originally published in Advanced Treatment Techniques for the Manual Therapist: Neck. 2013.)

Note: This blog post article is the sixth in a series of six posts on the

Anatomy / Structure of the Cervical Spine for Manual Therapists.

The Six Blog Posts in this Series are:

- Introduction to the Cervical Spine

- Cervical Spinal Joints

- Motions of the Cervical Spine

- Musculature of the Cervical Spine

- Ligaments of the Cervical Spine

- Precautions When Working the Neck