Upper Crossed Syndrome – Introduction

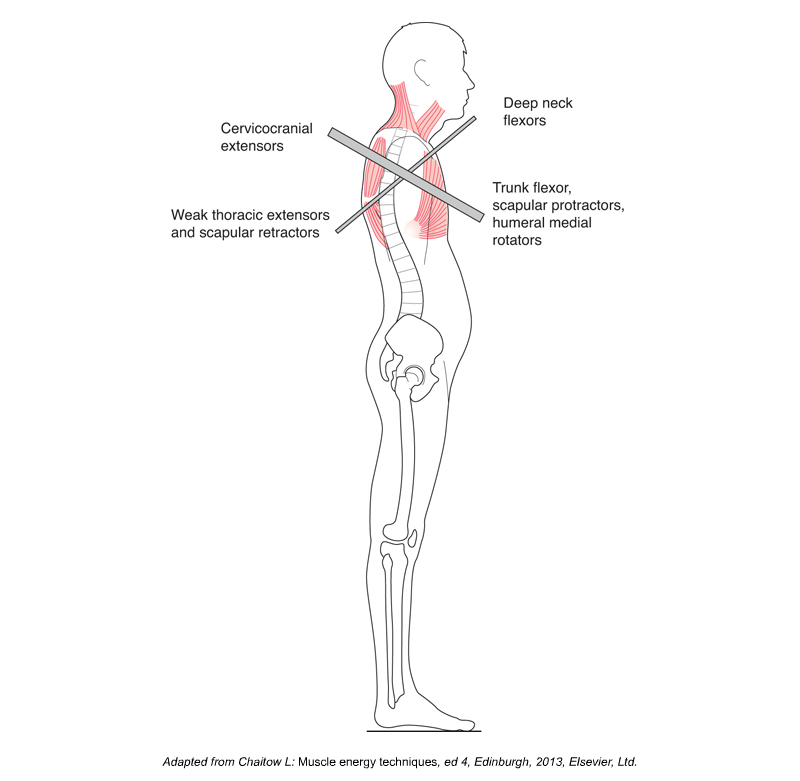

Lateral view of upper crossed syndrome, which involves hyperkyphotic thoracic spine, protracted shoulder girdles, and medially rotated arms. Permission: Joseph E. Muscolino.

Upper crossed syndrome describes the characteristic pattern of dysfunctional tone of the musculature of the shoulder girdle/cervicothoracic region of the body. This condition is given its name because an “X,” in other words a cross, can be drawn across the upper body when viewed from the side. One arm of the cross indicates the muscles that are typically tight/overly facilitated and the other arm of the cross indicates the muscles that are typically weak/overly inhibited. This condition is designated as the upper crossed syndrome because a similar pattern of dysfunctional muscle tone called the lower crossed syndrome is found across the pelvic girdle/lumbosacral region. Both the upper and lower crossed syndromes were initially described and named by a Czech physician and researcher named Vladimir Janda. Note: “Rounded shoulders” is a term that is often used to describe the rounded forward shoulder and arm posture that is part of the upper crossed syndrome.

Causes of upper crossed syndrome

Upper Crossed Syndrome. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3ed (Elsevier, 2017).

The primary cause of upper crossed syndrome is chronic postural stress to the upper body. Most tasks that we perform require us to work down and in front of ourselves, causing us to flex the upper spine, protract the shoulder girdles, and medially (internally) rotate the arms at the glenohumeral joints. Examples include working at a keyboard, using a cell phone, reading a book in our lap, or tending to a baby. Maintaining this posture necessitates the contraction and shortening of certain muscles and the inhibition and lengthening of others. Often, the presence of lower crossed syndrome or a rounded lumbopelvic posture (posteriorly tilted pelvis with a hypolordotic or kyphotic lumbar spine) will predispose the client/patient to develop upper crossed syndrome.

The muscles that are chronically contracted and shortened end up becoming overly facilitated and tight while the muscles that are chronically lengthened end up becoming inhibited and weaker (Table 1). Ironically, even the lengthened weakened muscles can gradually become tight as they attempt to oppose the shortened facilitated muscles (and even the shortened tight muscles can become weak due to the altered length tension relationship). For this reason, upper crossed syndrome often results in opposing muscle groups that are described as locked short and locked long, neither of which are strong and efficient in their contraction capability.

Table 1 – Upper Crossed Syndrome Musculature

| Overly facilitated (“tight”) muscles | Overly inhibited (“weak”) muscles |

| Pectoralis major | Rhomboids |

| Pectoralis minor | Middle and lower trapezius |

| Subclavius | Serratus anterior |

| Upper trapezius | Longus colli and capitis (deep neck flexors) |

| Levator scapulae | Infraspinatus and teres minor |

| Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) | Thoracic erector spinae |

In addition to the pattern of muscle engagement created by a chronic rounded posture, some sources believe that there is a predisposition for certain muscles in the body to become overly facilitated and tight, and for others to become overly inhibited and weak. It is posited that flexors and medial rotators that are needed to achieve fetal position tend toward facilitation; and extensors and lateral rotators tend toward inhibition. Other sources state that larger, superficial muscles that function primarily to create movement tend toward facilitation, and deeper small muscles that function primarily for stabilization tend toward inhibition. While these divisions should not be taken as absolutes, these patterns do seem generally to be true.

In addition to the facilitation/inhibition of musculature by the nervous system, once the upper crossed posture has been assumed for a long time, this posture is further entrenched by the formation of fibrous fascial adhesions (“fuzz” in the parlance of Gil Hedley) in the tissues. In time, even the bones involved, primarily the vertebrae of the upper thoracic spine, will gradually deform based on the physical forces placed upon them; the increased flexion posture will cause the anterior vertebral bodies to compress, resulting in a wedge shape that only serves to further perpetuate the flexion posture.