Shoulder Impingement Syndrome

This is the 1st of 3 blog post articles on Shoulder Impingement Syndrome.

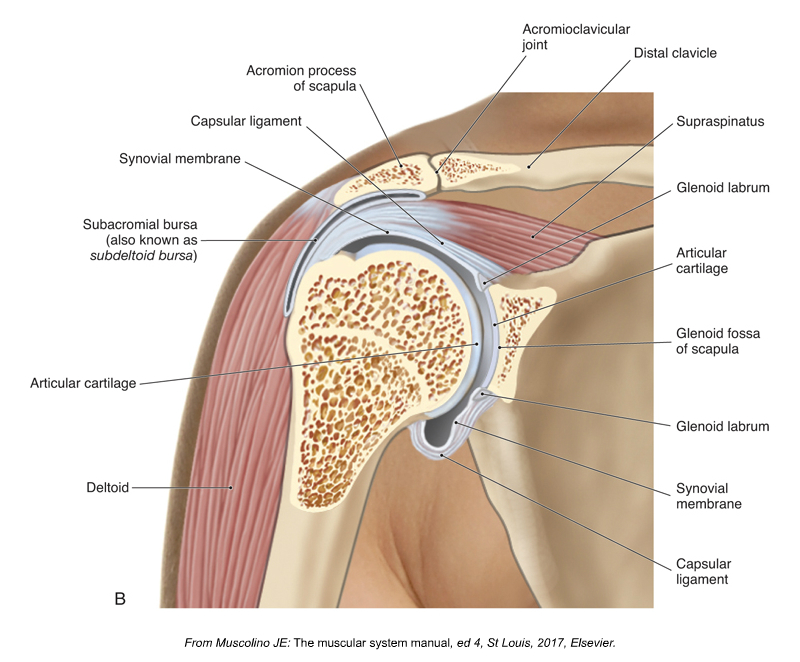

Shoulder Impingement Syndrome. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3ed (Elsevier, 2017).

Shoulder impingement syndrome is a condition in which the distal tendon of the supraspinatus and the subacromial bursa (also known as the subdeltoid bursa) become impinged between the head of the humerus and the acromion process of the scapula. Sometimes the long head of the biceps brachii is also involved. There are a number of reasons that this condition can occur. Following are the six major causes of shoulder impingement syndrome.

- Medially Rotated Arm

- Weak Scapular Upward Rotators

- Tight Scapular Downward Rotators

- Weak Rotator Cuff Musculature

- Hypomobile Sternoclavicular Joint

- Shape of the Acromion Process

This article covers the first two in the list: medially rotated arm & weak scapular upward rotators.

Medially Rotated Arm

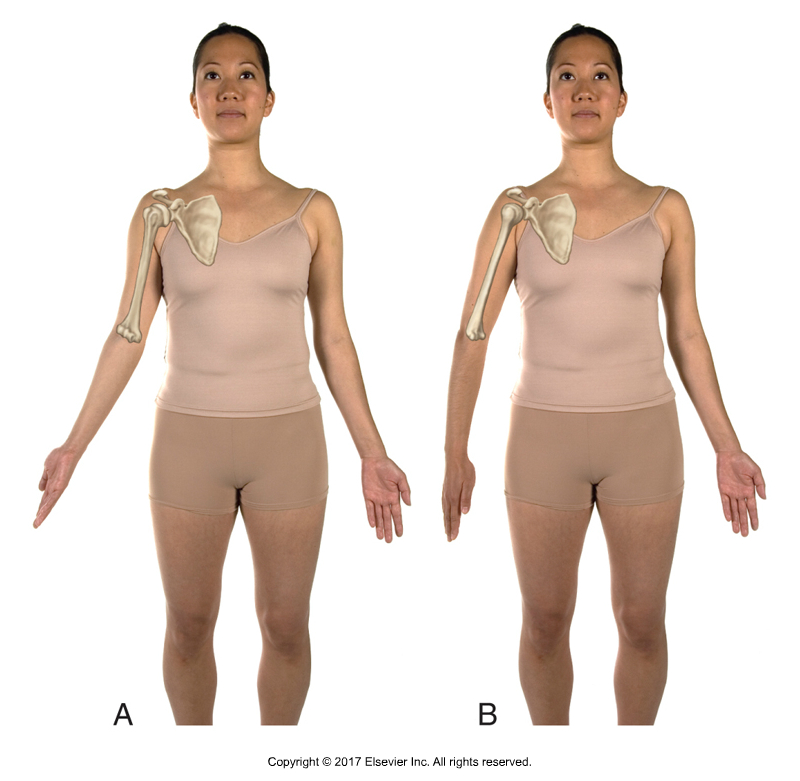

A, Laterally rotated arm. B, Medially rotated arm. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3ed. (Elsevier, 2017).

When abducting the arm at the glenohumeral (GH) joint, the head of the humerus approaches the acromion process. To allow for sufficient space, the arm should be laterally (externally) rotated so that the lesser tubercle on the head of the humerus is lined up with the acromion process. If the arm is instead medially (internally) rotated when abducted, the greater tubercle will be in line with the acromion process instead. Because the greater tubercle is larger, there will not be sufficient space and it will be contact the acromion process above, impinging the structures located between these two bony landmarks, namely the distal tendon of the supraspinatus and the subacromial bursa. For this reason, whenever abducting the arm to approximately 90 degrees or more, the arm should be laterally rotated. However, people with the postural distortion pattern of medially rotated arms, usually as part of upper crossed syndrome, are unable to sufficiently laterally rotate the arms and therefore shoulder impingement syndrome occurs. This postural distortion can occur because of tight (overly facilitated) medial rotators (e.g., pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, teres major, anterior deltoid) and/or weak (overly inhibited) lateral rotators (e.g., teres minor, infraspinatus, posterior deltoid).

(Click here for the blog post article: What is Upper Crossed Syndrome and What Are Its Causes?)

Weak Scapular Upward Rotators

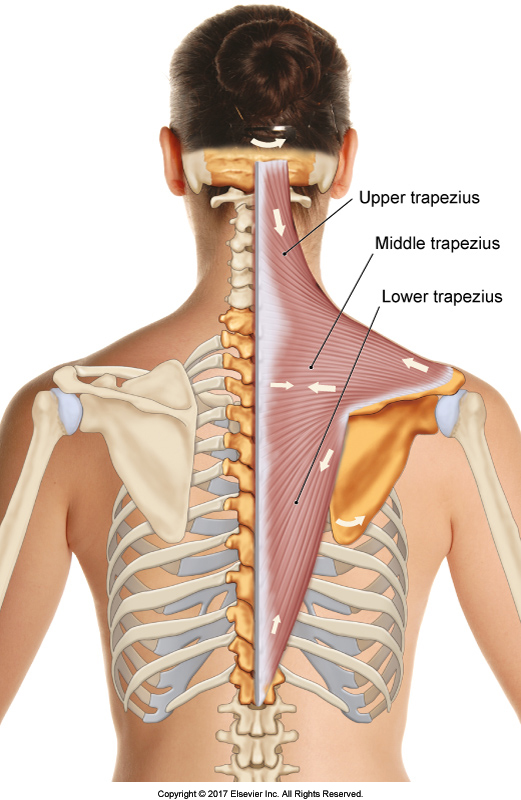

Trapezius. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. The Muscular System Manual – The Skeletal Muscles of the Human Body, 4th ed. (Elsevier, 2017).

During arm abduction, the scapular upward rotation musculature needs to contract for two reasons: 1) to stabilize the scapula and prevent it from downwardly rotating, and 2) to actually upwardly rotate the scapula.

Stabilizing the Scapula

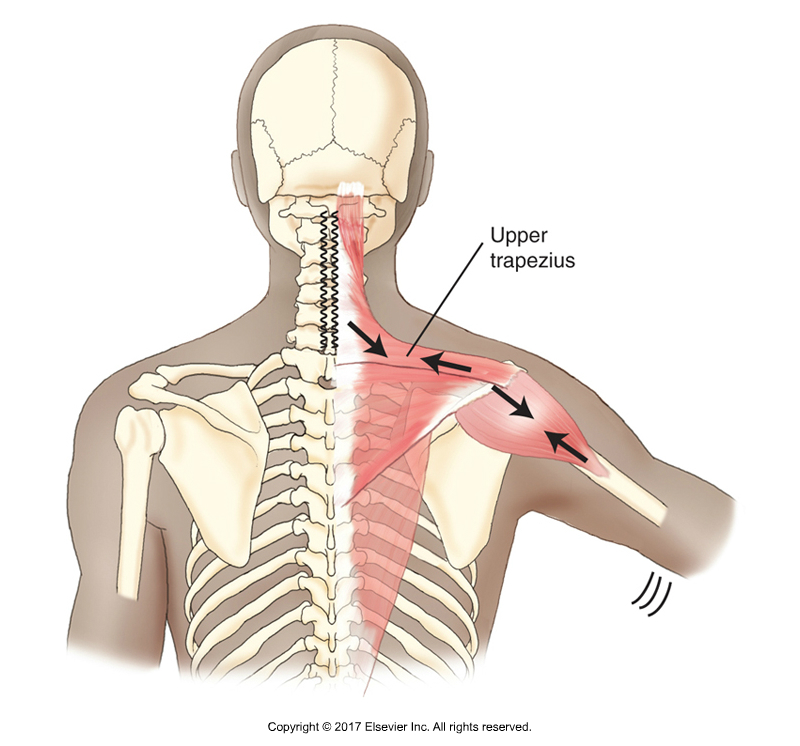

Upper trapezius stabilizing the scapula against the pull of the deltoid. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3rd ed. (Elsevier, 2017).

When the deltoid contracts to abduct the arm at the GH joint, it would also cause the scapula to downwardly rotate. However, if the scapula downwardly rotates when the humerus is abducting, the head of the humerus and the acromion will approximate each other and impinge the supraspinatus and subacromial bursa between them. Therefore, whenever abducting the humerus (as well as flexing it), it is important for scapular upward rotation musculature to engage isometrically to stabilize the scapula and prevent it from downwardly rotating. The major scapular upward rotators are the upper trapezius, lower trapezius, and serratus anterior. If these muscles do not engage for any reason during arm abduction (perhaps because they are weak or inhibited by the nervous system), impingement syndrome can occur. For example, if the upper trapezius has a myofascial trigger point that causes pain, then it might be inhibited from contracting, even if it theoretically has the strength to be able to contract. Or perhaps the upper trapezius and/or other upward rotators are simply weak.

Upwardly Rotating the Scapula

When the arm initially abducts, as stated here, upward rotation musculature of the scapula must engage isometrically to stabilize the scapula and prevent it from downwardly rotating. However, after approximately 30 degrees of humeral abduction, the scapula has to not only be stopped from downwardly rotating, it must actually be upwardly rotated to create the space needed between the head of the humerus and the acromion process of the scapula as the humerus continues to abduct. This coupling of humeral motion with scapular motion is termed scapulohumeral rhythm. In fact, of 180 degrees of arm abduction, fully 1/3 of the motion, 60 degrees, is due to scapular upward rotation. If the scapular upward rotator musculature is weak/inhibited and does not engage concentrically sufficiently to create the needed upward rotation of the scapula, then shoulder impingement syndrome can occur.

Tight and Weak?

One of the scapular upward rotators is the upper trapezius. Because the upper trapezius is so often tight, we do not often think it as possibly being weak and unable to contract to create upward rotation. However, tight musculature at baseline tone should not be confused with strong musculature. A muscle can be tight at baseline tone yet still not be sufficiently strong to contract sufficiently when a stronger contraction is needed, such as actually moving the scapula through its upward rotation range of motion.

This is the 1st of 3 articles on shoulder impingement syndrome.

The three articles are:

- Medially Rotated Arm & Weak Scapular Upward Rotators

- Tight Scapular Downward Rotators & Weak Rotator Cuff Musculature

- Hypomobile Sternoclavicular Joint & Shape of the Acromion Process