Note: This is the fourteenth blog post article in a series of 14 articles on Assessment/Diagnosis of musculoskeletal conditions of the neck (cervical spine). See below for the other articles in this series.

- A previous set of blog post articles discussed the musculoskeletal conditions of the neck that a manual therapist is most likely to encounter.

- This series of blog post articles has introduced and explained how to perform orthopedic assessment tests that are available to the manual therapist to assess these musculoskeletal conditions.

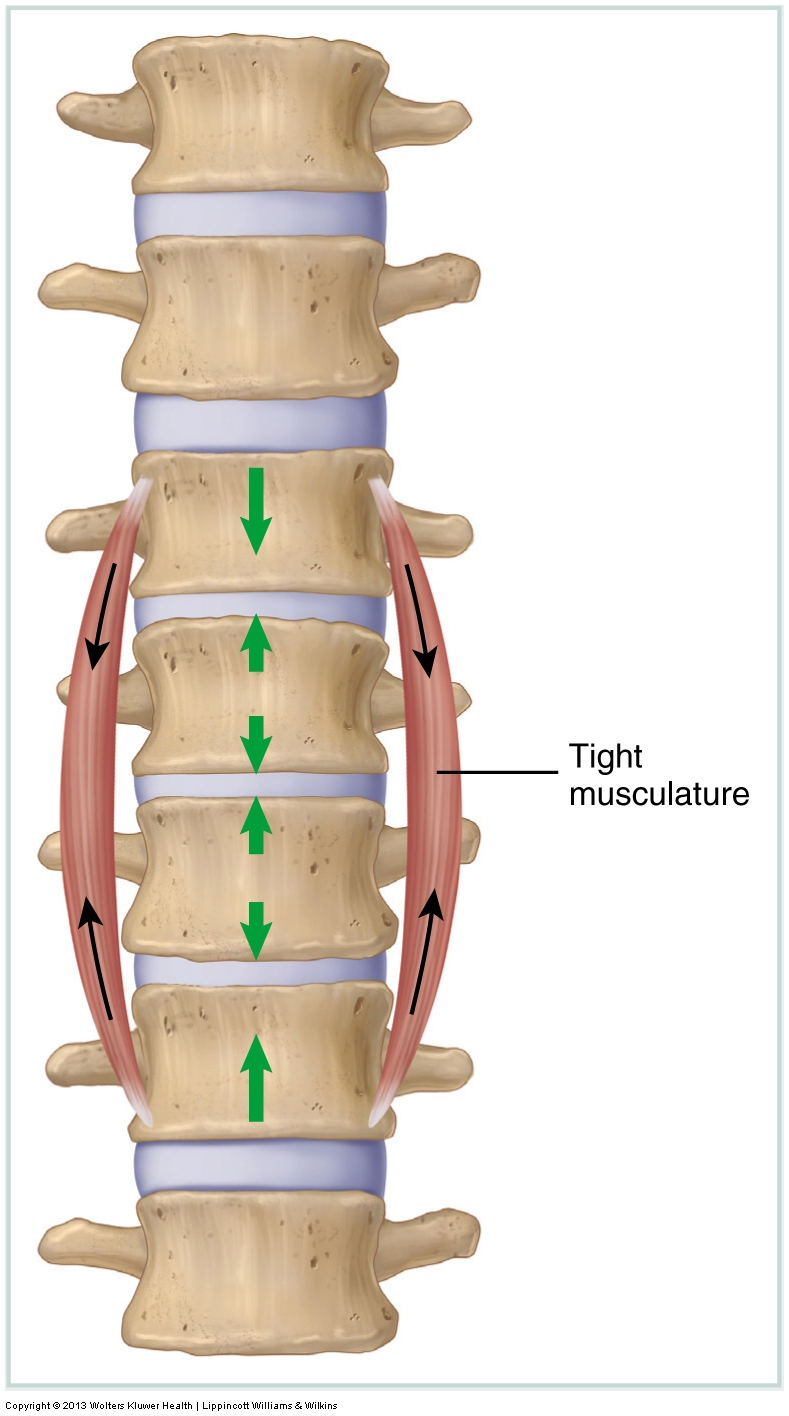

Hypertonic Musculature

Tight muscles are assessed by measuring the client’s passive range of motion (ROM). If a ROM is restricted, then the antagonistic muscles (generally located on the other side of the joint) to that motion are most likely tight. Tight musculature is not the only tissue that can restrict joint motion. Whenever an active or passive ROM is restricted, any taut tissues on the other side of the joint may contribute to the restriction in motion, including fascial ligaments and joint capsules.

Whether they are a result of increased active baseline muscle tone or adhesions, the treatment options available to the manual therapist to help loosen tight musculature and other soft tissues are many, ranging from soft tissue manipulation (massage), stretching, joint mobilization (Grade IV or Grade V depending on your scope of practice), and hydrotherapy.

Joint Dysfunction

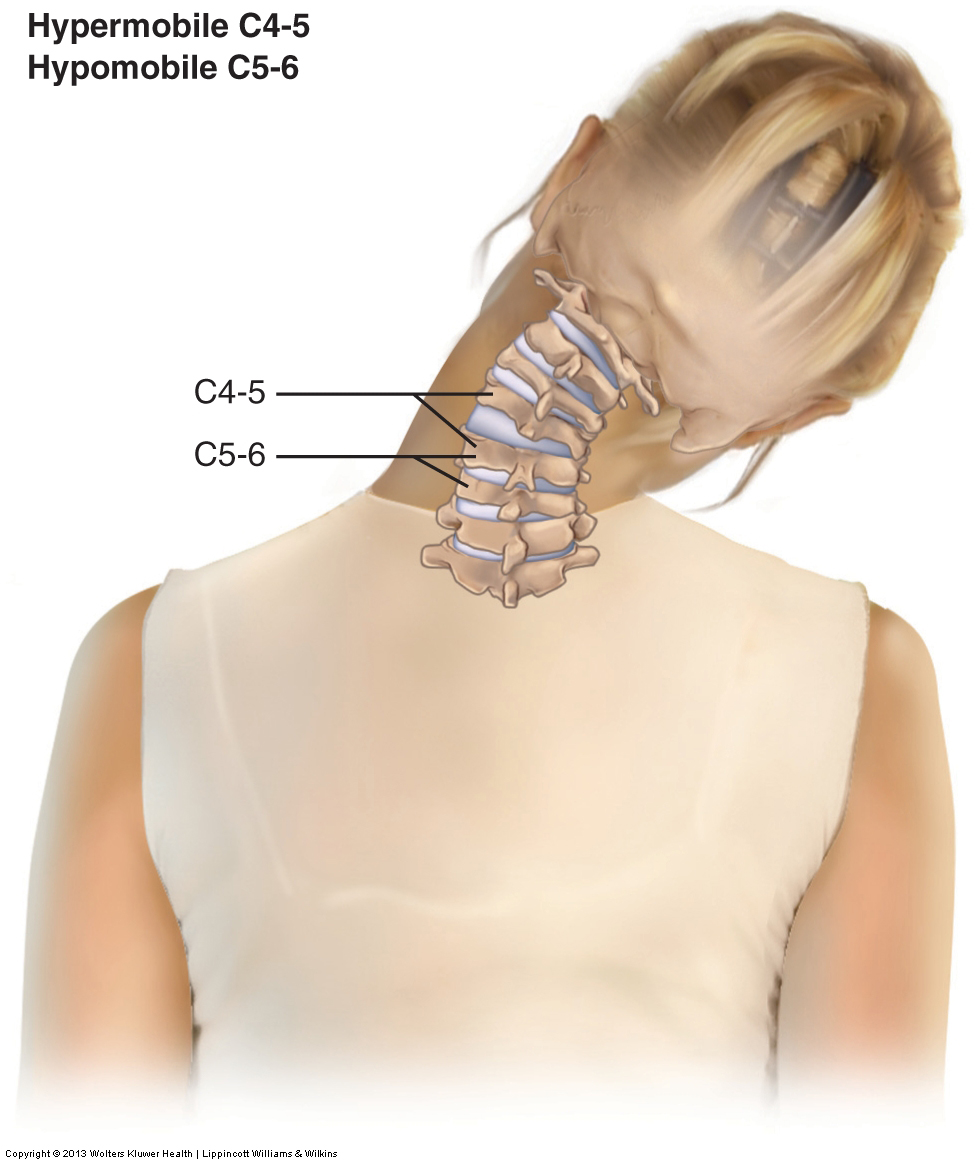

Joint dysfunction is assessed with motion palpation (joint play) assessment.

If a specific segmental vertebral level is found to be hypomobile, then the only effective treatment option is to perform joint mobilization technique. If a client has a hypermobility, there is little to nothing that a manual therapist can do to directly help because every treatment tool that a manual therapist employs is aimed at increasing mobility, not decreasing mobility. However, if the joint hypermobility exists as a compensation for an adjacent hypomobility, then the hypermobility may be alleviated if the adjacent hypomobility is mobilized. Further, if pain syndromes are relieved (perhaps due to global tightness of musculature and/or myofascial trigger points), then muscle strength might be increased because of facilitation of the musculature by the nervous system.

Note: Strengthening musculature around a hypermobile joint is helpful. If strength training is within your scope of practice/license, then it should be employed.

Sprains and Strains

Assessing a ligamentous sprain or a muscular strain can be done by using active ROM, passive ROM, and manual resistance. The acronym commonly used to describe the care routine for an acute sprain or strain is RICE (rest, ice, compression, and elevation). RICE care should continue as long as inflammation is present in the tissues. This may be days, weeks, or even months or more—do not follow a cookbook rule for ice application. If inflammation is present, icing is appropriate.

Note: There is currently renewed debate regardless the efficacy of icing based on decreasing inflammation. However, one persistent beneficial reason for icing is decreasing pain, which otherwise would likely up-regulate (overly facilitate) muscle tone in an effort by the body to splint and protect that region of the body. This could also then result in use/overuse/ misuse/abuse and fatigue of the musculature, then leading to inhibition and an inability to stabilize the joints of that region of the body, leading to further musculoskeletal sequelae.

Care for a chronic sprain is usually geared toward the tight muscles that usually occur as a compensation for the excessive motion. These tight muscles often cause pain and are in need of treatment. In addition, the best long-term approach that a client can take with a sprain is to strengthen the musculature of the region. Stronger musculature can compensate for the loss of stability of the stretched ligaments and help prevent painful muscle spasms.

Care for a chronic strain is geared toward loosening the muscles if they have become hypertonic, and also eliminating or decreasing the formation of further adhesions. For this reason, once adhesions have mended the strained (torn) muscle tissue and the tissue’s integrity has returned, it is important to begin soft tissue work and stretching to minimize tightness and prevent the formation of further adhesions. If there is any doubt about whether tissue integrity has returned, consent from a physician should be obtained.

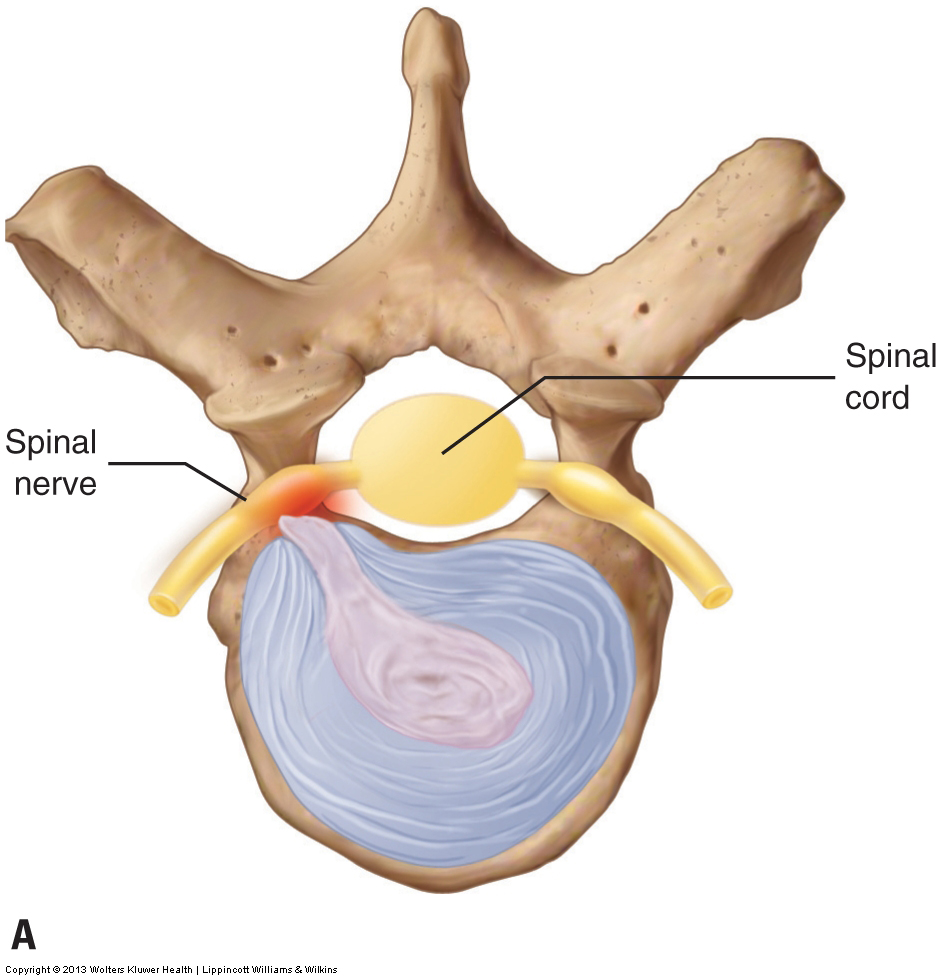

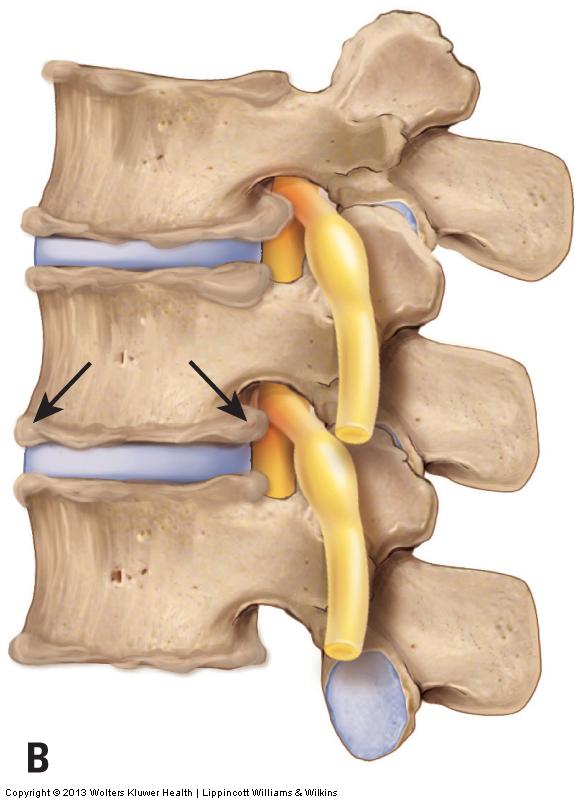

Pathologic Disc

Assessing a pathologic cervical disc condition, a disc bulge or rupture, can only be done definitively by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; or computed tomography [CT] scan). However, the foraminal compression test, cough test, Valsalva maneuver, cervical distraction test, and slump test may also be used. Although these assessment procedures are not as accurate as an MRI, they are usually effective at accurately assessing a pathologic disc that is moderate or marked in severity. If a cervical disc bulge or rupture is moderate or severe in presentation, it will likely produce a positive test result for most or all assessment procedures. However, a mild case may produce a negative result for many of the tests and a positive result for others. If there is any question about whether a client has a pathologic disc bulge or rupture, it is advisable to refer the client to a physician for a definitive diagnosis.

Treating a client with a cervical disc problem contraindicates doing anything that would increase pressure on the disc, thereby increasing the size of the bulge or rupture. Strong compression to the spine should be avoided, and all movements of the client’s cervical spine should be done with caution. If the disc condition is posterolateral, as most disc problems are, the client’s neck and head should not be extended and should not be laterally flexed to the side where the disc condition is located. If the disc problem is midline posterior, extension should be avoided. Beyond this, as a rule, anything that increases the referral symptoms of the disc lesion is contraindicated.

The primary focus of manual therapy is to loosen the tight muscles that surround the disc because they can increase compression on the disc, furthering the problem. As a general rule, Western-based Swedish strokes are usually fine as long as the pressure is not so great that the vertebral joints are actually moved, thereby placing stress on the discs. Because of the movement involved in stretching and joint mobilization, these treatment techniques should be avoided or done prudently at or near the level of the disc lesion. Cervical traction/distraction, if performed prudently, is indicated and can be beneficial for relieving disc pressure.

Osteoarthritic (OA) / Degenerative Joint Disease (DJD)

Physicians assess osteoarthritis (OA) / degenerative joint disease (DJD) by radiograph or other radiologic examination such as MRI or CT scan. Manually, DJD is difficult to assess through palpation unless it is marked or severe in degree. In these cases, palpation may be able to detect bone spurs that are superficially located around the outer margins of the facet joints. Advanced DJD will also impede motion of the affected joints, so passive ROM will be decreased and will often have a hard palpatory end-feel to the motions.

There is nothing that a manual therapist can do to directly affect the bone spurs of DJD itself. However, manual therapy can play an extremely important role, indirectly. The principal cause of DJD is physical stress to the joint, and one of the components of the physical stress is the compression force caused by tight muscles that cross the joint. If manual therapy relaxes tight muscles, less physical stress will be placed on the joint, and that can lead to a decrease or cessation in the rate at which the condition progresses. Therefore, even though manual therapy cannot reverse the condition, it can decrease its progression.

If the DJD is advanced and the client has a bone spur that is pushing on adjacent tissue, causing inflammation, another treatment option is the use of cryotherapy (the application of ice). If the bone spur is pressing on a spinal nerve, then any positioning/stretching/joint mobilization that increases that compression should be avoided.

Note: Physicians often blame OA/DJD as the cause of the client’s pain when it is not. This is due to the general lack of appreciation and understanding on the part of the medical establishment of the importance soft tissue function. Certainly, when advanced, OA/DJD can seriously contribute to the client’s musculoskeletal (neuro-myo-fascio-skeletal) condition. However, as a manual therapist, you might be the only health care provider that assesses the contribution of soft tissue dysfunction, so do not abrogate this role regardless of the diagnoses with which the client presents.

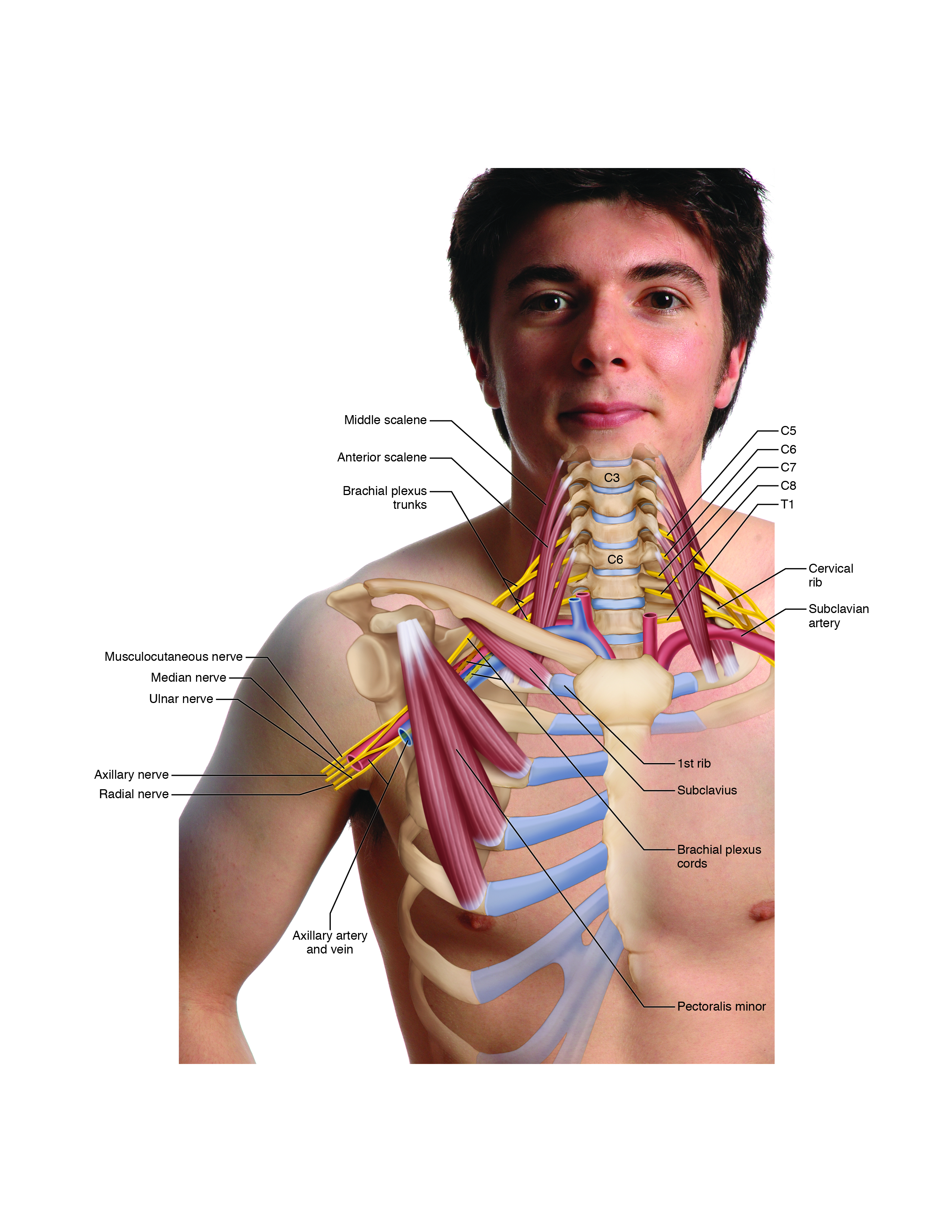

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

The various forms of TOS are assessed using Adson’s test, Eden’s test, Wright’s test, and the BPTTs, as well as palpation of the pectoralis minor, subclavius, scalenes, and other muscles. It is particularly important to offer home care advice to clients with this condition because TOS is often caused by rounded back / rounder shoulder posture (usually part of a larger postural dysfunctional pattern known as upper crossed syndrome). It is most important to educate the client about proper postures of the upper back and shoulder girdles.

Anterior scalene syndrome is assessed with Adson’s test, as well as palpation of the anterior and middle scalenes. The manual therapist’s role is to relax the scalene muscles. This can be accomplished through the use of heat, massage, and stretching.

Costoclavicular syndrome is assessed with Eden’s test, as well as palpation of the pectoralis musculature, scalenes, and subclavius. The manual therapist’s role is to relax whichever muscles are tight and causing the clavicle and first rib to approximate each other. This can be accomplished by using heat, massage, and stretching. Strengthening of the scapular retractors is also important.

Pectoralis minor syndrome is assessed with Wright’s test, as well as palpation of the pectoralis minor. The manual therapist’s role is to relax the pectoralis minor. This can be accomplished by using heat, massage, and stretching. Strengthening of the scapular retractors is also important.

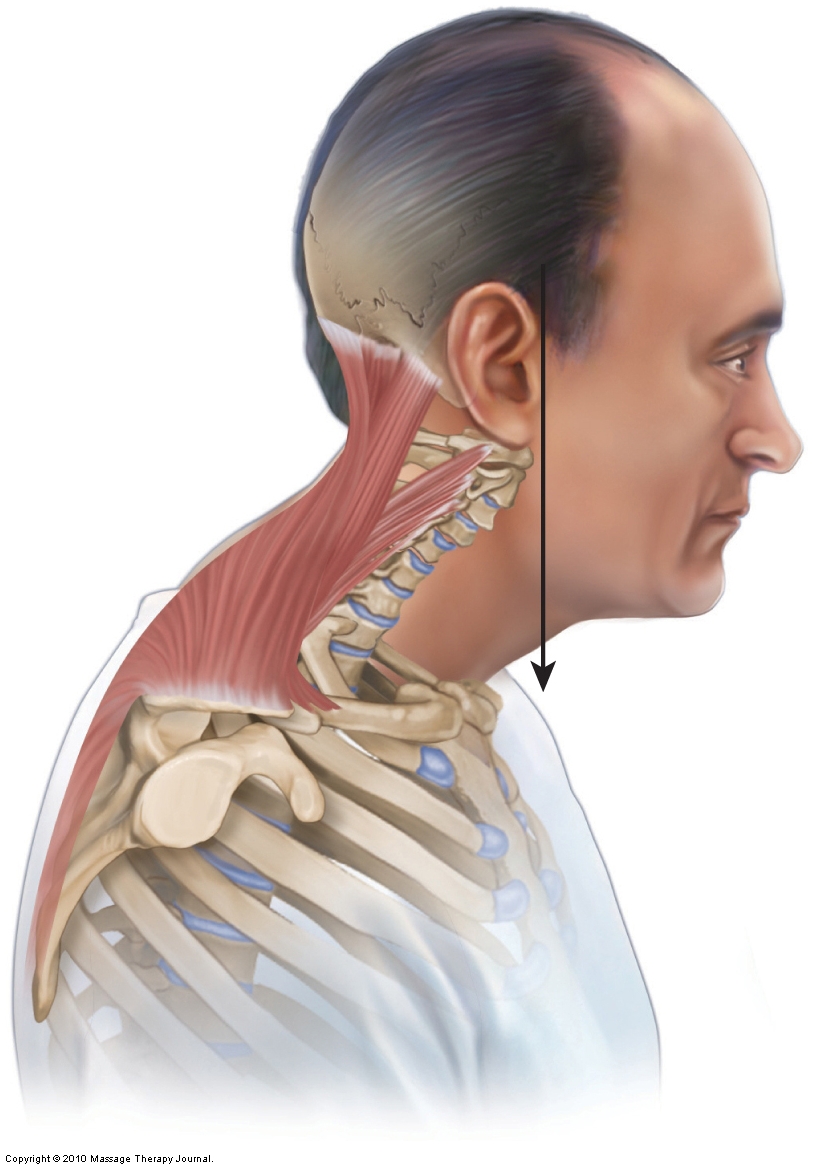

Forward Head Posture

Forward head posture usually involves a hypolordotic lower cervical spine along with a hyperlordotic head/upper cervical spine. Although physicians assess altered cervical curves with a lateral view radiograph of the neck, it is also easy to assess a forward head posture along with the associated cervical curve postural dysfunctions with postural examination and palpation of the cervical vertebrae.

When a hypolordotic cervical curve is present secondary to acute muscle spasming from a physical trauma such as whiplash, the manual therapist’s role is to relax these spasmed muscles, normalizing the muscle pulls on the spine. The hope is that relaxing the spasmed muscles will allow the normal curve to return. However, if the cervical hypolordosis results from chronic poor posture, although some improvement may occur, it is unlikely that soft tissue work can fully restore the normal lordotic curve. A combination of manual and movement (strength) training is likely necessary for true and lasting relief.

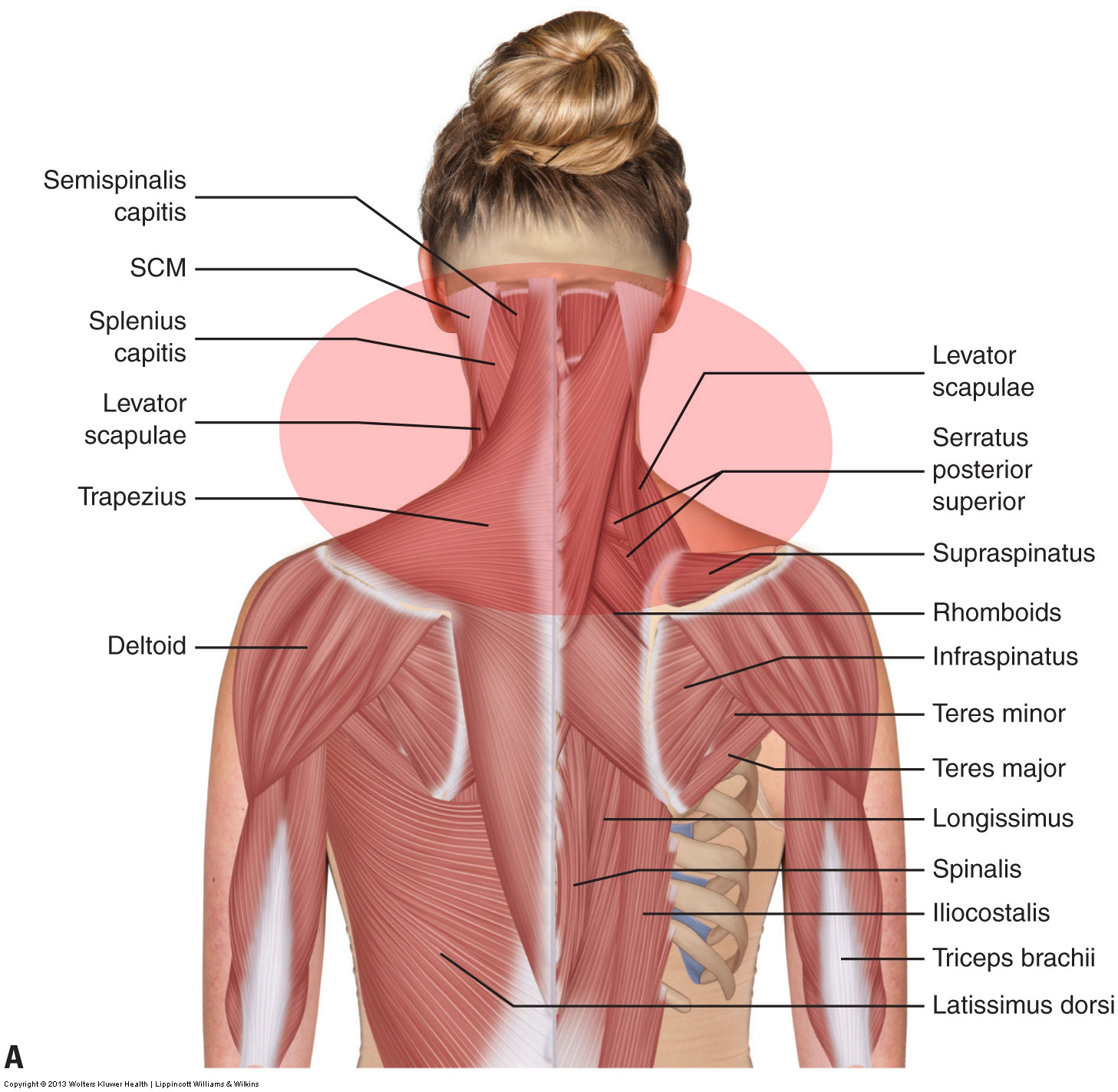

Treatment should focus on loosening the tone of the protractors of the head, such as the rectus capitis posterior minor and obliquus capitis superior, and relaxing and alleviating pain from the tight cervical extensor muscles, especially the extensors of the upper neck, which are contracting isometrically as a result of the anteriorly held head posture. Treatment should consist of heat, soft tissue manipulation (massage), and stretching. Because chronically tight muscles often create restrictions of joint motion in the region, joint mobilization of the cervical spine would likely be beneficial. Of course, if the cervical curve remains hypolordotic, the extensor musculature will tend to tighten up again from overuse as it works to maintain the imbalanced posture of the head. Therefore, if a hypolordotic cervical curve cannot be corrected, then the extensor musculature of the neck will need care on an ongoing basis.

Treatment should also be focused on the anterior flexor musculature of the cervical spine that might be locked short (e.g., SCM, scalenes, and longus musculature).

It is particularly important to offer home care advice to clients with this condition, because loss of the cervical curve often comes from prolonged postures in which the client holds the neck and head forward in a flexed/protracted position. It is most important to educate the client about proper postures of the neck.

Tension Headaches

Assessing a tension headache is done via the health history and palpation of the musculature of the cervicocranial region (neck and posterior head) , including the occipitalis. It is also valuable to assess for underlying causes of the tight musculature, such as forward head posture.

Treatment for a client who suffers from tension headaches is directed at loosening the tight muscles of the neck, usually tight posterior extensor muscles. This can be done with heat, massage strokes, and stretching. Because joint dysfunction hypomobilities often coexist with tight muscles, the joints should also be assessed. If hypomobilities are present, joint mobilization should be performed.

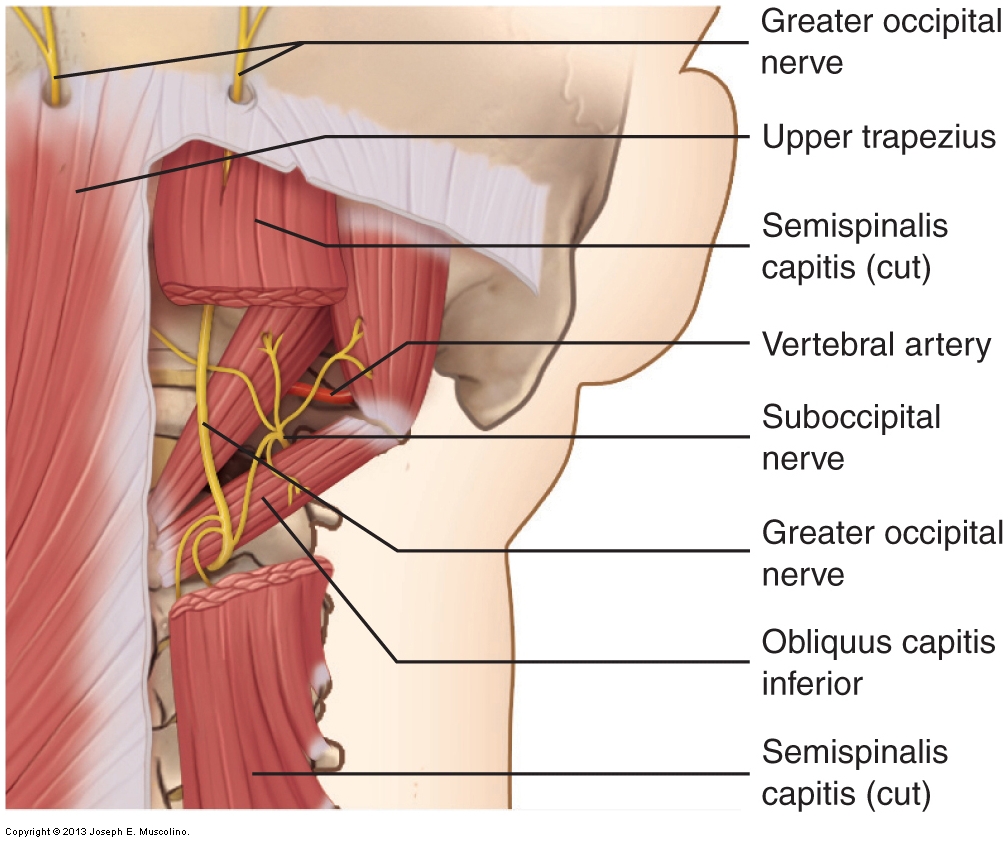

Greater Occipital Neuralgia

There is no definitive assessment procedure for greater occipital neuralgia. Palpation of the upper trapezius, semispinalis capitis, and obliquus capitis inferior should be done. A possible indication of greater occipital neuralgia is when pressure is applied to the area where the greater occipital nerve emerges through the upper trapezius (near its occipital attachment) and this pressure causes referral of pain or tingling (any altered sensation: paresthesia) to the back of the scalp. However, it is also possible that this sensory referral is a result of a myofascial trigger point in the region.

Treatment of greater occipital neuralgia consists of releasing the nerve’s entrapment in the semispinalis capitis and upper trapezius muscles. This is best accomplished by using soft tissue manipulation (massage), especially deeper pressure if the entrapment is in the semispinalis capitis. Heat and stretching also help to relax the muscles of this region.

This blog post article is the fourteenth in a series of 14 blog post articles on Assessment/Diagnosis of musculoskeletal (neuro-myo-fascio-skeletal) conditions of the neck (cervical spine).

The articles in this series are:

- Introduction to Assessment/Diagnosis of the Neck

- Verbal and Written Health History

- Overview of Physical Examination Assessment

- Postural Assessment

- Neck General Orthopedic Assessment: Range of Motion and Manual Resistance

- Palpation Assessment

- Motion Palpation (Joint Play) Assessment

- Special Orthopedic Assessment Tests for the Neck – Space Occupying Conditions

- Special Orthopedic Assessment Tests – Space Occupying Conditions – Slump Test

- Orthopedic Assessment of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome – Adson’s, Eden’s,Wright’s

- Orthopedic Assessment of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome – Brachial Plexus Tension Test

- Special Orthopedic Assessment Tests – Vertebral Artery Competency Test

- Treatment Strategy and Treatment Techniques

- Assessment and Treatment of Specific Musculoskeletal Conditions