Shoulder Impingement Syndrome

This is the 2nd of 3 blog post articles on Shoulder Impingement Syndrome.

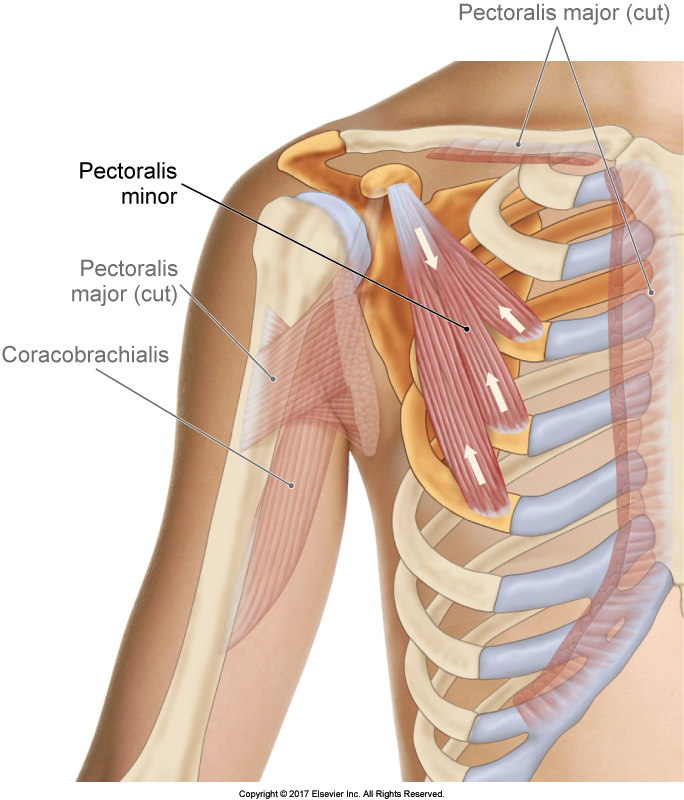

The Pectoralis Minor. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. The Muscular System Manual – The Skeletal Muscles of the Human Body, 4th ed. (Elsevier, 2017).

Shoulder impingement syndrome is a condition in which the distal tendon of the supraspinatus and the subacromial bursa (also known as the subdeltoid bursa) become impinged between the head of the humerus and the acromion process of the scapula. Sometimes the long head of the biceps brachii is also involved. There are a number of reasons that this condition can occur. Following are the six major causes of shoulder impingement syndrome.

- Medially Rotated Arm

- Weak Scapular Upward Rotators

- Tight Scapular Downward Rotators

- Weak Rotator Cuff Musculature

- Hypomobile Sternoclavicular Joint

- Shape of the Acromion Process

This article covers the second two in the list: tight scapular downward rotators & weak rotator cuff musculature.

Tight Scapular Downward Rotators

For scapular upward rotation to occur, scapular downward rotator musculature must lengthen. Therefore, if the downward rotation musculature is tight (overly facilitated) at baseline tone, it might not be flexible enough to sufficiently lengthen to allow for upward rotation to occur. Therefore, shoulder impingement syndrome can occur. The major downward rotators of the scapula are the pectoralis minor, rhomboids, and levator scapulae. Unfortunately, the pectoralis minor is one of the most commonly tight (overly facilitated) muscles in the body. It is a major protractor and depressor of the scapula, which is a common posture that find ourselves in when working down and in front of our body. Therefore, it is often tight as a part of the postural distortion of protracted scapula, which is usually part of a larger postural distortion pattern known as upper crossed syndrome.

(Click here for the blog post article: How Do We Treat Upper Crossed Syndrome with Manual Therapy?)

Weak Rotator Cuff Musculature

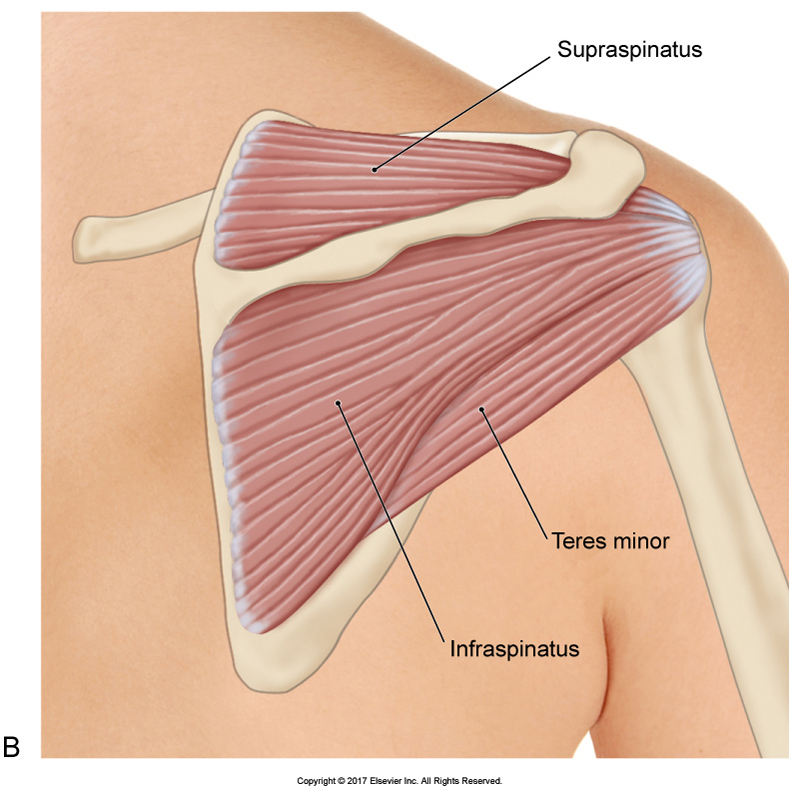

Three of the four rotator cuff muscles (the subscapularis is not seen). Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. The Muscular System Manual – The Skeletal Muscles of the Human Body, 4th ed. (Elsevier, 2017).

When the deltoid contracts to create abduction, its line of pull at anatomic position is actually directly (or nearly directly) vertical. Therefore, it should pull the head of the humerus directly superior into the acromion process, causing impingement of structures located between the head of the humerus and the acromion process, therefore shoulder impingement syndrome. This is usually prevented by rotator cuff musculature engagement, especially the lower fibers of rotator cuff musculature (teres minor, infraspinatus, and lower fibers of subscapularis). These rotator cuff fibers contract isometrically to stabilize and hold the head of the humerus down into the glenoid fossa while the distal end of the humerus (the shaft) is being lifted up into abduction. This concept is actually true for all upward motions of the shaft of the humerus from anatomic position (i.e., flexion, extension, and adduction as well). If the rotator cuff musculature is weak and/or inhibited and does contract in coordination with the deltoid, then shoulder impingement syndrome can occur.

This is the 2nd of 3 articles on shoulder impingement syndrome.

The three articles are:

- Medially Rotated Arm & Weak Scapular Upward Rotators

- Tight Scapular Downward Rotators & Weak Rotator Cuff Musculature

- Hypomobile Sternoclavicular Joint & Shape of the Acromion Process