Upper Crossed Syndrome and Thoracic Hyperkyphosis

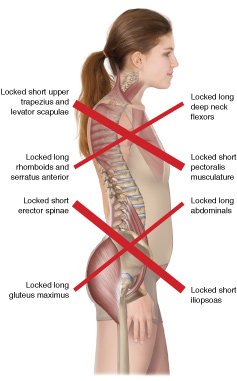

Upper and Lower Crossed Syndromes. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Artwork: Giovanni Rimasti.

The postural distortion pattern known as upper crossed syndrome has many components to it. It involves:

- thoracic hyperkyphosis

- hypolordosis of the cervical spine

- hyperextension of the head upon the atlas at the atlanto-occipital joint

- forward head carriage

- protraction of the shoulder girdles

- medial (internal) rotation of the arms at the glenohumeral joints.

Each and every one of these components is important in and of itself, and can cause pain and dysfunction. But for many clients, one of these components, thoracic hyperkyphosis, is the primary critical component, and if not sufficiently addressed, will lead to failure to improve the rest of the pattern.

Thoracic Hyperkyphosis

I would propose that the critical, the essential, component of upper crossed syndrome is thoracic hyperkyphosis. At least for middle-aged and senior clients, this is the primary postural distortion that usually drives all the rest of the postural distortions of this larger distortion pattern. And if not treated, will lead to failure to achieve any lasting improvement for our clients who present with this condition. Following are the steps by which thoracic hyperkyphosis causes the rest of the postural distortion pattern to occur.

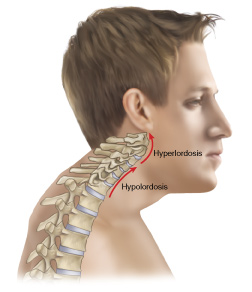

Hypolordosis of the Cervical Spine

The cervical spine sits on the top of the thoracic spine. The superior surface of T1 acts like the pedestal upon which the cervical spine rests. If the angle of T1’s superior body changes due to thoracic hyperkyphosis, the curve of the cervical spine must change. When the thoracic spine is hyperkyphotic, the superior surface of T1 becomes much more vertical than with a healthy thoracic posture. As a result, C7 of the cervical spine must begin being projected much more anteriorly, and the rest of the cervical spine follows the kyphotic posture of the thoracic spine, therefore being less lordotic, hypolordotic. Because lordosis is a curve of extension, a hypolordotic neck is in greater flexion.

This posture results in increased loading of the cervical discs (the more anterior of the spinal joint complex). Increased loading increased compression and the likelihood of disc pathology. Posteriorly, cervical flexion opens up the facet joints, which places them in a less stable posture, decreasing the ability of the cervical spine to absorb weight bearing shock forces that occur with each step we take. Further, a hypolordotic, flexed cervical spine leads to adaptive shortening of the flexor musculature of the neck: scalenes, longus muscles, and the sternocleidomastoid.

Hyperextension of the Head at the Atlanto-Occipital Joint

Figure 5. Anterior (Forward) head carriage, Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Artwork: Giovanni Rimasti.

So now we have thoracic hyperkyphosis leading to hypolordosis of the lower and middle cervical spine. When the lower and middle cervical spine is hypolordotic, the head would not be level – the eyes would be oriented downward toward the floor, which would make it difficult if not impossible to see where we are going. Further, the inner ears would not be level making it more difficult to judge proprioception (our ability to sense our position in space and our movement through space). To compensate for this hypolordosis of the lower and middle cervical spine, the posture of the head at the AOJ must become hyperextended, in effect, hyperlordotic. This results in jamming of the facet joints, increasing the weight-bearing load upon them. By Wolff’s law (calcium is laid down in response to physical stress), the osteoarthritic process would likely be accelerated. This also allows for adaptive shortening of the upper cervicocranial extensor musculature in the suboccipital region (e.g., rectus capitis posterior major), leading to hypertonicity and myofascial trigger points. Further, the increased pull of these muscles upon the scalp increases the chance of the client developing tension headaches. The increased extension of the head at the atlanto-occipital joint also leads to a constant stretching pull upon the suprahyoids, which can lead to increased tension stresses upon the temporomandibular joints (TMJs), which can lead to TMJ syndromes.

The Sternocleidomastoid

Sternocleidomastoid – Permission Joseph E. Muscolino. The Muscular System Manual – The Skeletal Muscles of the Human Body, 4th ed. (Elsevier, 2017).

When we look at the adaptive shortening of cervical spinal musculature as part of upper crossed syndrome, the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) is particularly relevant. The SCM crosses the lower and middle cervical spinal joints anteriorly so it flexes the lower and middle cervical spine. But it crosses the upper cervical spinal joints, especially the atlanto-occipital joint, posteriorly, so it extends the head at the AOJ. For this reason, the SCM is adaptively shortened and tightened with both the hypolordosis of the (lower and middle) cervical spine and with the hyperextension of the head at the AOJ.

The Chicken and the Egg

By the age-old wisdom of the chicken and the egg, once a postural distortion results in adaptive shortening of musculature, in other words, locked-short musculature. This increased muscle tightness then plays back on the skeletal postural distortion, in effect, locking it in place. The skeletal postural distortion causes the tight musculature, which causes the skeletal postural distortion – the chicken and the egg.

Forward Head Carriage

Now that thoracic hyperkyphosis leads to the lower cervical spine being hypolordotic, the head is projected anteriorly to the body so that instead of its center of weight being balanced over the trunk, it is imbalanced over thin air. This should result in the head and neck falling into flexion (until the chin essentially hits the chest) due to the force of gravity, unless some force opposes this movement. That force will likely be isometric contraction of the cervicocranial extensor musculature in the back of the neck (e.g., upper trapezius, splenius capitis, semispinalis capitis, etc.,). This leads to use, overuse, misuse, and abuse (a la Leon Chaitow’s famous verbiage) of these muscles, leading to tightness, and likely myofascial trigger points, pain, and dysfunction.

DID YOU KNOW THAT DIGITAL COMT HAS MULTIPLE FOLDERS WITH HUNDREDS OF VIDEO LESSONS THAT ADDRESS FUNDAMENTAL ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY, PATHOMECHANICS, ASSESSMENT, MASSAGE, STRETCHING, AND JOINT MOBILIZATION? ALL ORIENTED TOWARD MANUAL AND MOVEMENT THERAPISTS (INSTRUCTORS AND TRAINERS). CLICK HERE TO LEARN MORE.

Protraction of the Shoulder Girdles

Returning now to the upper extremity, when the spine rounds forward into thoracic hyperkyphosis (hyperflexion), the natural pull of gravity on the shoulder girdles (scapulas and clavicles) is to make them fall forward, in other words, protract. Protracted shoulder girdles result in shortening (locked short) of the protractor pectoralis musculature and lengthening (locked long) of the retractor musculature (rhomboids and trapezius, especially the middle trapezius). Beyond causing the creation of myofascial trigger points, a tight pectoralis minor can also cause pectoralis minor syndrome version of thoracic outlet syndrome, resulting in neurovascular compression of the brachial plexus of nerves and/or subclavian/axillary artery and vein.

Medial Rotation of the Arms

Thoracic Joint Mobilization into Extension. Permission Joseph E. Muscolino.

When the thoracic hyperkyphosis leads to to the shoulder girdles falling forward into protraction, they also fall inward, leading to increased medial (internal) rotation of the arms at the glenohumeral joints. Beyond shortening the pectoralis major (and latissimus dorsi and teres major) musculature, and stretching the infraspinatus and teres minor, leading to locked short and locked long musculature with all of its effects as previously explained in this article, all overly shortened and overly lengthened muscles become weaker by something known as the length-tension relationship curve. Also, with a medially rotated posture of the head of the humerus, the lesser tubercle would now be lined up with the acromion process during abduction of the arm, leading to the increased likelihood of impingement syndrome of the distal tendon of the supraspinatus and subacromial bursa when the arm is raised into abduction. There, upper crossed syndrome can even lead to shoulder tendinitis!

Putting it all Together

Putting all this together, upper crossed syndrome can result in many “fires” that need to be put out all around the body with competent manual therapy, as well as competent movement therapy (strengthening and stabilizing, etc.,)…

HOWEVER, the critical component that usually drives all of this postural distortion pattern is the thoracic hyperkyphosis / hyperflexion. At least this is almost always the case with middle-aged and older clients.

Solution?

So what is the solution? What is the critical component? Whatever manual and movement therapy is necessary to lessen the thoracic hyperkyphosis. Most every manual and movement technique can have great value here, especially those oriented at stretching the anterior tissues and strengthening the posterior tissues, but I would like to propose one specific technique, that if left out, at least in most of our middle-aged and older clients, will result in a futile attempt to ameliorate this condition. That is joint mobilization of the thoracic spine into extension. We must introduce extension motion into the facet joints of the thoracic spine and it must be specifically targeted to reach the joints that are hypermobile. This usually requires very specific application of force, in other words, joint mobilization. General stretching of the spine into extension with a client who has rigid thoracic joints stuck in flexion will usually result in the person initiating the movement from the joints of the spine that can move into extension. This will often be the lumbar spine (or perhaps some thoracic spinal joints that are mobile and compensating for the hypomobile rigid joint levels). Thus we have the typical hypomobile tissues being allowed to persist due to the compensatory hypermobile tissues. Treatment must specifically target the hypomobile joints, hence joint mobilization technique. Joint mobilization can be done Grade IV (slow oscillations) or Grade V (fast thrust). The application depends on your licensure and technical expertise. Please always stay within your legal and ethical scope of practice.

The point of this article is to make the case that for most of our clients who present with the postural distortion pattern known as upper crossed syndrome, it is important, perhaps absolutely necessary, to include thoracic spinal joint mobilization technique into extension as part of the treatment plan to address the thoracic hyperkyphosis.

(Click here for the blog post article: How Do We Treat Upper Crossed Syndrome with Manual Therapy?)

DID YOU KNOW THAT DIGITAL COMT HAS MULTIPLE FOLDERS WITH HUNDREDS OF VIDEO LESSONS THAT ADDRESS FUNDAMENTAL ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY, PATHOMECHANICS, ASSESSMENT, MASSAGE, STRETCHING, AND JOINT MOBILIZATION? ALL ORIENTED TOWARD MANUAL AND MOVEMENT THERAPISTS (INSTRUCTORS AND TRAINERS). CLICK HERE TO LEARN MORE.